Posted 13 years ago

164 Notes

More on the iPhone 4 signal issue

Previously, I did some simple testing of reception strength on my iPhone 4 and concluded that I couldn’t see any problems. I’ve now done some more thorough testing, however, and have reason to think I was wrong. Warning: this is very long and nerdy.

UPDATE: read Anandtech’s article, they figured out how to make the iPhone 4 display true signal-to-noise ratios and have thus been able to use more rigorous science than I could. They agree with my conclusions though!

UPDATE 2: I have a followup piece discussing the press release from Apple this morning about these problems.

What should we test?

Apple have issued a statement on the issue:

Gripping any phone will result in some attenuation of its antenna performance, with certain places being worse than others depending on the placement of the antennas. This is a fact of life for every wireless phone.

This suggests there are two things we should examine:

- Hypothesis 1: that holding the iPhone in a conventional grip with the left hand reduces signal strength.

- Hypothesis 2: that the loss of signal strength isn’t as bad when human skin is not in contact with the steel band around the edge of the phone.

My credentials

I’m fractionally more than Just Another Internet Dude on this subject. I have a Ph.D in wireless network planning techniques from Cardiff University, and I have worked for Keima, a company writing commercial software that helps cellular operators design their networks for optimum performance. I’m not an antenna engineer by any means, but I do have a modest command of how cellular networks are built.

Fucking signal bars; how do they work?

To understand part of what’s going on, it’s necessary to realise what the signal bar indicator on a cell phone does (and doesn’t) mean.

Wireless engineers don’t think in terms of bars, they think in terms of signal to noise ratio, which is often called SNR. When you’re not using the phone, a few times a second it checks it can still hear the control channels that the cell tower uses to send messages to the phones – messages like “here’s an incoming call, wake up and deal with it”. Of course, in today’s crowded airwaves, your signal is my noise, and vice versa; usually what happens when the signal suddenly drops away is that something has started up nearby and is interfering with your reception. This is like when a car with faulty shielding drives past and you lose your AM radio to the blaring sound of the car’s coil discharging.

So, the phone has this number in its head which represents the SNR and that number is constantly fluctuating up and down as the airwaves around you teem with random signals, reflections, and other interference. This isn’t a particularly nice thing to show end users, so the phone does two things. Firstly, it takes that ever-changing number and does a moving average on it to smooth out those rapid spikes. Then, it applies some sort of magic formula to approximate that complicated number into a 1-to-5 scale, which it then puts on the screen as bars.

The magic formula is basically made up by the design engineers as they see fit, and it can vary from phone to phone and even between software releases on the same phone. If someone is kicking it old school and getting five bars at your house with their Motorola RAZR and you’re getting three on your Nokia 8210, that doesn’t mean their phone is better than yours. It might just mean that Motorola’s designers made their bars work differently, or it might not.

The tl;dr version of this is: the signal strength bars are almost meaningless and should not be relied on.

Incidentally, this also explains what’s going on when you have a strong signal, attempt to make a call, and can’t connect. The bars only indicate how well your phone can listen to the cell tower. They don’t tell you anything about how well the tower can receive your phone, but that’s a pretty important part of making a call. Similarly, the phone doesn’t know anything about what’s going on in the cell provider’s network past the tower; if you’re on a really busy cell it might not have any spare outgoing circuits to direct your call to, so even if the radio is working fine, you might still not be able to get through. If you’re on AT&T it’s probably all of the above at the same time of course.

How I tested

The office I work in is lucky enough to be directly under a 3G mast. Now, not a lot of people realise this, but that’s generally pretty bad for signal strength – cell towers are designed to radiate outwards, not up and down. Sure enough, we have a weak signal spot inside the building, in the stairwell directly under the mast itself.

So having identified an area of marginal signal, and knowing that we can’t trust the signal bars for shit, what can we do? Old iPhones had a hidden field test mode that showed you the signal to noise ratio as numbers, as well as all manner of other useful network data, but it’s gone in iOS4. The best idea I came up with was to use the speedtest.net iPhone app to stress test the cellular network. This isn’t ideal, because the numbers that come back are as much dependent on the upstream network beyond the cell itself, but I think I’ve reached valid conclusions anyway. There may be some drive test apps in the jailbreak app store that could yield better data, but I don’t think Apple allow App Store apps access to this sort of juicy data.

I identified three ways to hold the phone:

- Flat on my hand so I am only touching the glass back. This is my control position.

- Held in my hand in the usual manner.

- Held in the same way, but with a piece of cloth between my hand and the phone, so I am not touching the metal band. This simulates using a cover on the phone such as Apple’s Bumper.

I ran the speed tests five times in each configuration, then repeated through the flat on hand and normal grip configurations again. In this manner I aimed to control for variations in network performance beyond the cell tower.

Results of first test

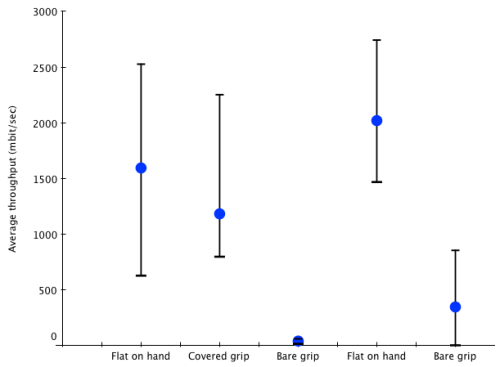

The blue dot against each type of test shows the mean download speed achieved across the five repetitions of the test. The error bars show the highest and lowest speed recorded during those five repetitions.

Clearly, there is a lot of random variation here. However, I feel we can make some progress towards our hypothesis.

Firstly, moving from the “flat on palm” to “covered grip” (i.e. holding the phone normally with the left hand but with a piece of cloth between phone and hand), we see a small drop in download speeds. On the phone’s display, this was shown as the signal strength meter going down from five bars to three; despite that seemingly large drop the phone’s speed is not substantially affected. (I was running out of time to do these tests, so the covered grip setup was only tested once).

However when the cloth was removed and I held the phone in my bare hand, a much sharper decline in performance was recorded. In the first set of five results, the phone had a really, really hard time, dropped all the way down to EDGE transmission, and at one point completely failed to transfer data at all. In the second set, results were better – the signal strength meter showed 1 bar, but stayed in 3G mode – but the speeds were still notable slower than in either of the other two test scenarios.

Conclusions of first test

- Gripping the hand around the base of the phone reduces reception, whether the hand is insulated from the phone or not. This is not unexpected. As antenna design consultant Spencer Webb notes, almost all modern cell phones put the antenna in the lower part of the case, and you’d always expect some attenuation from surrounding the phone by a fleshy bag of salty water. MacRumours has video footage of other phones showing this. TJ Luoma notes this is even listed in the manual for his ancient Nokia 2320.

- However, when this cloth cover is removed, radio performance nosedived further than was recorded with a bare-handed grip. This is a factor that doesn’t apply to other modern cell phones, because other modern cell phones don’t have electrically active components in contact with bare skin.

Second test: what if you are not in a marginal signal area?

As discussed above, I deliberately did all this testing right under the cell tower, where the signal is actually quite weak. John Gruber has suggested that the problem doesn’t happen when signal isn’t already marginal.

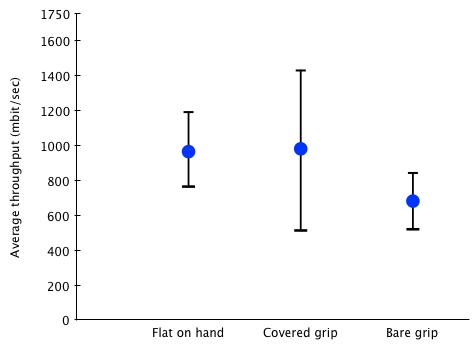

To test this, I moved to the top floor of a nearby carpark, where I had direct line of sight to the cell tower. I then repeated the bare-handed grip and flat-on-hand tests.

Results of second test

I think it’s pretty clear that there was still a performance penalty from gripping the phone in my bare left hand, despite the strong signal conditions.

Conclusions

Apple has issued conflicting advice about this issue.

- All phones do this.

- Using a case helps.

These two pieces of advice conflict because there are two underlying mechanisms at work here that damage the iPhone 4’s ability to receive a signal. The first is the commonplace attenuation that happens when a user holds the phone by the antenna; the second is the iPhone-only effect presumably caused by placing an electrically active antenna on the outside of the case. The attenuation on other cell phone models isn’t changed at all by using a case on them. In effect, with the second piece of advice, Apple are admitting there is something up with the iPhone 4.

So how bad is it?

It might not be a problem at all. Suppose the iPhone 4 was so good at plucking a signal out of the air that, even with a sweaty palm doing the Grippe of Deathe, it’s still as good as most other phones – and, bonus points!, with that hand removed it’s much better than other phones. Anecdotally, however, from the widespread reports of people being surprised by the number of dropped calls, I think this is unlikely.

If you’re in a strong signal area, you may not ever see the effect, because even with the attenuation from holding the phone you’ll still have plenty of signal left over. But that doesn’t mean you aren’t going to be affected by the issue unless you are never, ever in a weaker signal area – and the second test above suggests that 3G data transfer rates are still going to be slower anyway.

It might (might) be fixable in software. People are talking about things like calibration faults in the signal strength meter, or some sort of dynamic frequency allocation that doesn’t square with any bit of the GSM spec I’ve ever been exposed too. I’m uncertain about this. It doesn’t feel like a software fault to me.

But I think all of the above is unlikely. I think there’s some deeper problem here, and I await Apple’s formal response to the issue with interest.

A personal note

Taking my Objective Scientist Dude hat off now, I’d say that iPhone 4 is a fantastic device but a lousy phone. Placing calls from my office, my home, and my neighbourhood whilst walking my dogs, I’ve had 14 dropped calls in a little over two hours of talk time. I would have expect at most one dropped call per few hours of usage with my iPhone 3G.

I’m also suffering from the proximity sensor problem; during those two hours of calls I have had the proximity sensor stop working on half a dozen occasions, resulting in contact from my cheek hitting the pause, mute, facetime, and dialpad buttons. As an iPhone 4 owner, I am hopeful that this secondary issue can be fixed in software; it feels like a calibration problem. I’ve tried a few times to reproduce the fault whilst covering and uncovering the sensor with my finger but so far have been unable to do so.

Finally, I certainly think that Steve Jobs’s personal response, telling a customer to hold the phone differently, was a disgrace.

Replies

Likes

low-testosterone-symptoms liked this

low-testosterone-symptoms liked this  adderall-side-effect-blog liked this

adderall-side-effect-blog liked this buy-steroids-united-kingdom-blog reblogged this from penllawen

stickers-muraux-blog reblogged this from penllawen

stickers-muraux-blog reblogged this from penllawen betsys-vet-imaging-blog reblogged this from penllawen

foreclosure-listings-blog reblogged this from penllawen

steroids-uk-blog liked this

buyp90xcheap-blog liked this

buyp90xcheap-blog liked this  kelowna-bc-blog liked this

kelowna-bc-blog liked this penllawen posted this

- Show more notesLoading...