Out on the Laško

With the summer season come our beloved film festivals, the ones that combine cinema and holiday mood. The untiring Michael Pattison is already an expert in writing travel notes, covering his cinewalks all over the world, so we are excited to share his latest adventure at Kino Otok – Izola Cinema Festival, featuring churches, sunsets, his own pics + some football of course – kick on!

The bells began to chime at seven. Seven chimes first, then eight, then nine, and ten and eleven, then twelve and one, with one dong, two dongs, and three dongs marking every fifteen minutes in between. The sun flooded in, the heat sat on my sweating body like a thick stew, and the bells told me with dreadful regularity that they were going to render every morning from now until eternity an absolute write-off—except on Saturdays. Never have I been so simultaneously keen to cry with frustration and exhausted by the thought of any sort of protest.

I had the night before arrived via Trieste in Izola, the small fishing town east of the touristier Piran on Slovenia’s Adriatic coastline. Home to Nino Benvenuti (born 1938), arguably Italy’s finest ever boxer, Izola was incorporated into Yugoslavia in 1954. Before then, it was ruled by the Venetians, by the Holy Roman Empire, and by Napoleon; by the Austrian Empire, by Benvenuti’s Kingdom of Italy, and, very briefly during the Second World War, by the Germans. Jovial, punchy endurance seems to be built into this town, and the bells that bellow out from St. Maurus Church to the populace below speak of a stubborn and proud persistence that to this new arrival were a brazenly pious piss-take.

Perhaps I deserved it. Earlier this year I wrote an essay for Bradford International Film Festival’s catalogue on how such events interrelate and how many of them take place, with metaphorical significance, in close proximity to impressive churches. With their emphasis on something resembling togetherness and icon-worship, I suggested, cinemas are as much a gathering point for communal rituals today as any religious building. Was the church, built in 1547, ringing its bells in defiance or agreement? At any rate, beyond its age the church itself is not very impressive, and the film critic disabled by its deafening decibels was not at all impressed.

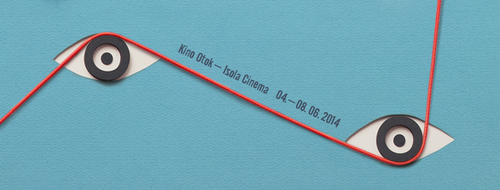

Then Sunday comes, and the sound of a choir emanates from the same vicinity like some cheekily angelic reminder that no emotional state is irredeemable. By that point of course I was open to surrender, battered as I had been by three full days and four very filling nights of scorching sun, oppressive heat and the unadulterated joys that attending a good film festival can entail (no claims of festival fatigue, please, we are… professional). The festival in question of course was Kino Otok – Izola Cinema, whose tenth edition ran from June 4th to 8th. Under festival director Lorena Pavlič and head programmer Varja Močnik, Izola’s International Film Festival is a sensibly-sized affair that niftily negotiates the formidable task of drawing in international guests while satisfying local attendees as well as its own ambitions to discerning cinephilia.

A couple of days after Kino Otok finished, I saw Till Nowak’s THE CENTRIFUGE BRAIN PROJECT / DAS ZENTRIFUGEN-GEHIRN-PROJEKT (2011) as part of a programme of International Short Film Festival Oberhausen shorts at the Slovenian Cinematheque in Ljubljana. I had seen this clever, funny faux-documentary at Curto Circuíto in Santiago de Compostela in December and mentioned it in my Bradford catalogue essay, referring to the centrifugal, overlapping, interrelating carriages of the imaginative fairground rides depicted therein as fitting metaphors of film festivals. Every festival is of course also an island, and yet at a time of diminishing subsidies and reactionary political currents, each embattled island must think up ways by which to connect with others like it.

Izola itself was once an island: its very name means “island”. Since the 1810s, however, it has been part of mainland Europe. Today it sits near the Italian-Slovenian border. The municipality of Izola is officially bilingual. In official artwork, the festival’s full title reads: “Kino Otok Isola Cinema”. The first two words are Slovenian; the second two are Italian. Both phrases translate to “cinema island”. But the order differs: literally, the phrase goes “cinema island island cinema”. Palindromes abound. It is easy to mix metaphors.

Borders form the subtext of TIR (2013), the first feature by documentarian Alberto Fasulo, who nevertheless channels previous working methods into a politically charged minimalist drama about long-distance Slovenian truck driver Branko (Branko Završan), a husband, father, and former teacher who makes his living transporting an endless supply of goods across a seemingly borderless Europe. Branko is joined for the first half of the film by colleague Maki (Marijan Šestak), as the film depicts with understated authenticity the minute details of a friendship binding two workers living together in such unalterably close proximity.

When Maki is dispatched elsewhere, the loneliness of the long-distance trucker is exacerbated. Though the decision to half its cast also brings a tendency to then over-dramatise proceedings with phone calls home, Fasulo’s self-shot road movie is a haunting and suitably aimless sketch of a contemporary Europe in which labour is not only alienating but also separates a person from his only source of political protest: other people. Every man is an island. In the final stages of the film, Branko transports fruit alongside a truckload of pigs, and Fasulo frames the latter vehicle through a reflective pane, so that his protagonist becomes a part of them. It is easy to force metaphors.

Borders are much more prevalent in Eloy Enciso Cachafeiro’s ARRAIANOS (2012), a loose and visually gorgeous reworking of a play by Jenaro Marinhas del Valle. Shot in a small village on the Galician-Portuguese border, Enciso Cachafeiro’s mysterious essay film matches the region’s territory-straddling location by effectively and comfortably positioning itself somewhere between documentary and fiction. Surface ripples are just the start: gradually and subtly, a textured portrait of local traditions emerges, as the filmmaker proceeds through a landscape that the rest of the world seems to have forgotten, and toward something more evocative of enlightenment.

Indeed, sunny horizons were the order of the day at Kino Otok this year. ARRAIANOS formed one part of a six-film programme (three features, three shorts) dedicated to the healthily luminous cinematic landscape of Galicia. Curated by Galician critic Víctor Paz Morandeira, the programme brought together a demonstrably fine selection of films from the semi-autonomous region of Northwest Spain that also included Lois Patiño’s COAST OF DEATH / COSTA DA MORTE (2013) and Oliver Laxe’s YOU ALL ARE CAPTAINS / TODOS VÓS SODES CAPITÁNS (2010). The reasons behind the recent proliferation of Galicia’s cinematic landscape are complex and intertwined, and although diminishing, bureaucratic funding procedures were raised as concerns by producer Felipe Lage Coro (Zeitun Films) in a panel discussion I moderated, the many awards and international critical acclaim garnered by this heterogeneous bunch of films suggests the quasi-movement might have a few more bright days ahead of it yet.

Another region-specific triptych showcased three short films by two Yugoslav-born and Belgrade-taught filmmakers: Croatian Ivan Salatić’s INTRO (2013) and Serbian Stefan Ivančić’s SPRINGTIME SUNS / PROLECNA SUNCA (2013) and MOONLESS SUMMER / LETO BEZ MESECA (2014). Made by a writer-director born in 1980s Yugoslavia, each film deals with themes of childhood, memory, and the pains of maturation in a formally lucid style that is refreshing and welcome at a time when too much of the festival circuit is pervaded by its own self-fulfilling genre of opaque miserabilism (indeed, the “festival film” is perhaps best defined as a prolonged in-joke without a punch-line). Comprising a programme called Song of Some Time, the three films here suggested between them that we might be on the verge of a burgeoning cinematic dawn in the Southern Slavic regions.

And then of course were the actual dawns of Izola. I watched at least three unfold, not long after the blood-orange moon had descended through the night sky (no moonless summer in Slovenia!). Sunrises are seldom as exciting or interesting as the cinema itself has forever made out, but during Kino Otok at least, there was a sense that the golden fireball around which our own humble, life-giving orb spins was eager to spring up and ascend to the heavens – as it demonstrated with alarming speed days later in the Slovenian capital, as I walked home after one last bottle of Laško pivo just as the day’s first train of commuters was pulling in.

Theirs is a generous sun. Up early like an excited, glowing child, its unwaveringly positive energy continues throughout the day, beating down upon for whomever the bells toll and testing the brave few who competed with such admirable vivacity in Kino Otok’s annual football match. By now a semi-serious affair, this year’s game pitted seven against seven for two gruelling 15-minute halves. With an arrogance and optimism completely undone by shoddy skills and woeful fitness, I was pleased to contribute where I could, and thrilled to have played for the victorious team that won the seven-goal thriller thanks to a catastrophic last-minute error by my colleague and opposite number Neil Young. His is the self-deprecatingly good-humoured leadership to which we all should aspire, and these words are dedicated to him.