Lights, Camera, Africa!!!

Nigeria – the most populous country and the largest economy in Africa, whose cinema industry, known as Nollywood, competes with Hollywood and Bollywood. Definitely a good starting point for our first visit to this continent! Luckily, we have a great guide – our new contributor Oris Aigbokhaevbolo (alumnus of Talents Durban 2014), who plunged into the Nigerian megapolis Lagos to report from the 4th edition of Lights, Camera, Africa!!! Join the ride!

Lights, Camera, Africa!!! is an unusual festival. First, for its courage in choosing to screen African independent films – a retinue of films less glamorous than their American counterparts and far less institutionalized than their European equivalents. It is unusual also for its lack of awards finale. Berlinale has the Golden Bear, Cannes – the Palme d’Or, while this year at Durban IFF Festival Manager Peter Machen unveiled the Golden Giraffe. Perhaps there is something to be said for a festival, where the highest thrill, for the audience, as for filmmakers, is the thrill of seeing and showing films. Purity of experience may rank lower than prizes, but it is the former than yields the latter.

In some respects, African independent cinema is a misnomer. In any case Nigerian independent cinema is certainly a misnomer. All of the cinema in the country is independent of something – of government, of studios, of whatever passes for the establishment in other climes. When Nigerians refer to independent cinema, it is the purest meaning of the word we reach for: a film produced without depending on the existing framework. Natural question: what is this framework?

A tricky question taking in the amorphousness of the country’s film culture. I hazard an answer still: the framework means marketers, a position occupied in Hollywood by distributors but over here not limited to the dissemination of film produce. Often the marketer decides the genre of the film, he may even outline a story, hire a screenwriter in pursuance of that story and then a director. In this arrangement, the director can never be auteur in the classic Cahiers du Cinéma sense. Like the studios, except Hollywood makes a decent gross that affords its time, these marketers like franchises. Films can have four parts, released simultaneously. Given these, perhaps a truer name for the titles Lights, Camera, Africa!!! showcases are meta-independent films? A little unwieldy but mostly correct, if you get past the snobbish prefix.

The non-awarding of prizes is not unique to Lights, Camera, Africa!!! While the festival ran at the Federal Palace Hotel in Victoria Island, Lagos, the European Film Festival, organized by the European Union’s delegation to Africa, was held a few metres away at Nigeria’s biggest cinema chain, Silverbird Cinemas. Having attended that festival since 2012, I can say that other than the pleasure of seeing film after film, a separate peak is the raffle for its audience. Perhaps European cinema, presumably not quite as accessible to foreign audiences, has to reward its crowd for their time? Mind you, festivals do need an opening and a lavish closing.

Still, there are no prizes or lotteries for the audience at Lights, Camera, Africa!!! For its lavish closing instead the festival shows a marquee movie – a film with considerable buzz, screened for free in a mutually rewarding exchange. Audiences are drawn to the festival in ways impossible for slimmer fares. The film, ahead of its release in national cinemas, receives word-of-mouth hype. The festival gets record visitors. Everyone is happy.

Last year’s marquee movie, for example, was the Tarantino and Iñárritu influenced CONFUSION NA WA (2013). Directed by young Nigerian director Kenneth Gyang and financed by the Hubert Bals Fund, the film chronicled the intersecting lives of six characters. With its unusual structure, CONFUSION NA WA offered Nollywood another path to moving forward. It went to cinemas later, and whatever figures it garnered at the box office can, in part, be traced to the buzz of reviews in the wake of its screening at Lights, Camera, Africa!!! Nor did it hurt that the film scored four nods at the African Movie Academy Awards.

This year OCTOBER 1 was selected as marquee movie. The film’s eponymous date refers to the day, in 1960, when Nigeria gained Independence from British rule. Suitably, OCTOBER 1’s last scene has Queen Elizabeth’s photo taken down and replaced with Nnamdi Azikiwe’s, the first President of Nigeria. Directed by Kunle Afolayan (who plays a small but pivotal role in the film), OCTOBER 1 stars Sadiq Daba, an actor honoured by the festival for his time on the small screen in the 1980s, the golden age of Nigerian television. It is the story of a serial killer in a village and the attempts of Danladi Waziri (Daba), a newly transferred police officer, to stop the killings before the country gains independence. The British District Officer, played somewhat woodenly, wants to pass on a clean slate to the former colony.

Daba and Afolayan graced the closing night of the festival, receiving applause, answering questions, taking playful shots at each other. The festival’s audience may have been relieved to see both smiling, as minutes before, onscreen, in OCTOBER 1’s most audacious (if gimmicky) sequence, Afolayan’s character nearly eviscerated Daba’s Waziri. During the Q&A, Afolayan took pride in informing the audience that every aspect of the film was directed, designed, dressed by Nigerians. Afolayan directed, Pat Nebo was art director, Yinka Edwards was in charge of cinematography (he deserves praise for the forest at night scenes), and Deola Sagoe provided costumes.

As a matter of fact, another film from the programme, HALF OF A YELLOW SUN (2013) by Biyi Bandele could have been the marquee movie as well. Although long released elsewhere, a problem with the Nigerian Film and Video Censor’s Board kept it away from cinemas until recently, so that it, too, drew a crowd. It is perhaps uncharitable to compare both films. Yet for their similarities, a relative assessment is inevitable. Both films cover roughly the same epoch – HALF OF A YELLOW SUN is set around the Civil War (1967 – 1970), while the events in OCTOBER 1 occur seven years earlier. A character in the latter film, burdened by the director’s own hindsight, predicts the events of the former. And in both films, the events forming a backdrop to the immediate story (a love story in HALF OF A YELLOW SUN, a crime plot in OCTOBER 1) are accurate but do not have so much of a consequence for the characters. The Independence in OCTOBER 1 merely supplies a deadline for the crime’s resolution. And in HALF OF A YELLOW SUN the war is so tangential to the story that any violence of some scale may replace the Nigerian Civil War.

Biyi Bandele, bred in Britain, is a first-time director. Coming from theatre, his set for HALF OF A YELLOW SUN is pristine, unlived-in, his characters are talky but show no spatial interaction with the environment. Beautifully shot, the film fails to convey the potency and urgency beauty is sometimes capable of conveying. I noted the employment of color and also the uselessness of it, the deployment reminiscent of a muted Wes Anderson scene deprived of that director’s inventiveness.

Although Nigerian, or partly Nigerian in Bandele’s case, both films are directed out of the sensibility to other cinema cultures. Bandele’s HALF OF A YELLOW SUN for its pace is a tad more spirited than British daytime soaps. Afolayan’s OCTOBER 1, in spite of the great lengths director and art director go to avoid inadvertent incursions of modern life into the sleepy disturbed village at the plot’s centre, succumbs to cultural anachronism in its filmmaking, re-creating for the audience set pieces casual viewers of Hollywood flicks have seen: a detective nursing a hurt; a killer with a cause, ridiculous to his victims but credible to him; and a tacked-on social message that succeeds but only just. This does not mar the film, it is quite enjoyable, yet it is a film that should yield its own idiom, pave its own way. Or else look askance at the Hollywood culture it apes, warily adapting for its purpose rather than present too faithful a transcription as it offers. Afolayan avoids originality, choosing in its place the ready-made handles of Hollywood. Being the more experienced director with three other films, Afolayan is the better filmmaker, his smaller budget film superior to HALF OF A YELLOW SUN. So that were the festival handing out prizes, he would be in pole position to take home Best Director. An Honorary Award could go to Bandele’s set designer.

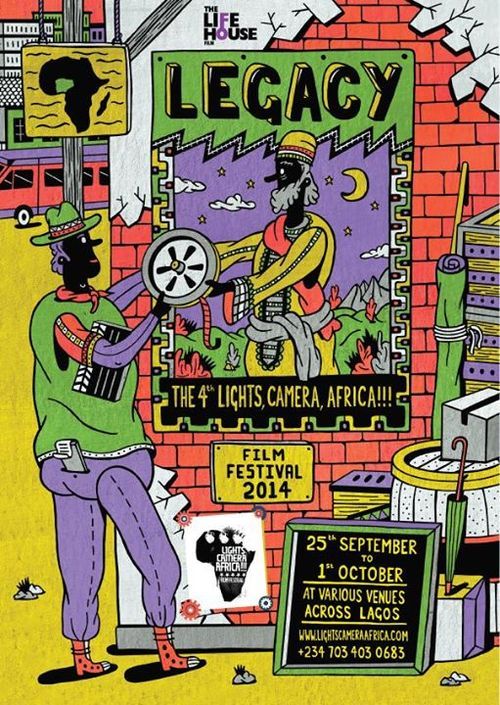

Young, at four years, so unable to look at its own nascent history, Lights, Camera, Africa!!! reflected not only on Nigeria’s political history but also on its cinema and television history. Themed Legacy for this reason, the festival listed important figures in African cinema in its brochure. The brochure preceded the list with a brief introduction: “Inspired by this year’s Legacy theme, we feature information on African screen icons. These individuals are pioneers in their craft—as actors, writers, directors and producers. Their work spans nearly a century of African storytelling—creating many firsts, subverting the status quo and appropriating it for themselves and for coming generations. What is telling and perhaps alarming is that information on a number of significant individuals is not freely accessible and is something to think about.” And in concluding, the brochure offered a necessary caveat: “This is by no means an exhaustive list, but merely a sampling of the constellation of artists who have cleared the path in African cinema.” Such internationally renowned names as Ousmane Sembène and Ken Saro-Wiwa (who directed a popular Nigerian sitcom in the 1980s but is clearly known for an event far removed from comedy) feature on the list. As do names known to Nigerians of a particular age: Ade ‘Love’ Afolayan, Eddie Ugbomah, Hubert Ogunde, Ola Balogun, James Iroha.

With many of these progenitors of African cinema necessarily or prematurely deceased, it was especially gratifying to see Chika Okpala, star of 1980s sitcom NEW MASQUERADE, speak to the audience about his time on the sitcom and the environment, from which the show was birthed. Now in his 60’s, it may have occurred to his audience that his onscreen persona was not much younger than the man is today: then in his early 30’s, he played an elderly man, age never explicitly stated, but depending on episode could be anything from early forties to late fifties. Accounting for the level of Nigerian filmmaking at the time, his transformation, in more familiar terms, probably demanded as much makeup and skill as was required for Marlon Brando to play Don Corleone in Coppola’s THE GODFATHER (1972).

Having Legacy as main theme meant a nosey poking into the past of a country that has recently removed the study of history from the curriculum. And after a while it seemed the theme was not directed inward, in the usual fashion of themes, to govern structure and instil order, but was a cri de cœur to Nigerian cultural establishments: “Take care of your legacy!” The brochure states, the fact “that information on a number of significant individuals is not freely accessible… is something to think about.” It may however be too late: responding to a question by a parent on the possibility of transferring the experience of seeing the NEW MASQUERADE to his children, Chika Okpala confirmed that the tapes, upon which episodes of the show were recorded, have been erased. For Nigerian television, the past is irrevocably past.

Consequently, if a secondary theme sprung from the films themselves, it was of a broader pattern of the neglect of history and culture. A look elsewhere for safekeeping and promotion of indigenous culture bound several films together. Bandele’s HALF OF A YELLOW SUN is partly British. Valiant Afolayan, to achieve the aged look he needed, purchased and borrowed items overseas. The irony in purchasing from without what is needed to portray an authentic within must have been clear to Afolayan. The experimental JOY, IT’S NINA (2012) by Jane Thorburn probes the emotional ambiguity of the reluctant immigrant, her longing for home clashing with her need for a better life, captured in images defying absolute comprehension.

This need for foreign nectar and its necessity, via funds or acclaim, is generally thought by Nigerians to be a unique Nigerian need. Here I admit a sliver of schadenfreude upon learning that the reality is different. Consider the Senegalese documentary 100% DAKAR (2014), showcasing and chronicling the work of young choreographers, musicians, graffiti artists, designers. The documentary is directed by Austrian filmmaker Sandra Krampelhuber. The artists themselves are supported by Institut Français. “We’re like little children left on our own,” says one of the protagonists about their plight in the country. Consider TAKING ROOT: THE VISION OF WANGARI MAATHAI (2008), where the Kenyan Nobel laureate declares: “My five years in America transformed me.” The film, directed by Alan Dater and Lisa Merton, is an American production. Like Nigeria, like Senegal, like Kenya – what exactly are cultural organisations indigenous to these countries doing for culture?

In J.D. OKHAI OJEIKERE: MASTER PHOTOGRAPHER (2013), directed, thankfully, by Nigerian filmmaker Tam Fiofori (himself deserving a documentary) together with Joel Benson, the eponymous photographer decried the situation. “I feel sad,” he said, “that what other people value in my work, my country doesn’t.” He died shortly after the film’s release. Oddly prescient, he told Fiofori: “Tam, you are making an obituary of me.” William Onyeabor, an avant-garde musician from the 1980s, is pursued by curious Americans in Jake Sumner’s documentary FANTASTIC MAN (2014). Hailed for his forward-looking innovation by Americans, he is largely unknown by Nigerians. But the neglect does not end at cultural heroes. It crosses into politics, with SEXY MONEY (2014), a documentary about sex workers returning from Europe, directed by the Dutch filmmaker Karin Junger. Same goes for THE SUPREME PRICE (2014), dealing with the country’s 1993 elections, directed by Harvard professor Joanna Lipper. And on and on. Put together, these films present Africa’s growing elision of its own storytelling.

Via cinema, the 4th edition of Lights, Camera, Africa!!! film festival captures the continent’s uneasy relationship with its own culture, its heroes, and its history. These films implore citizens and governments of the continent to be mindful. “Good or bad,” as a British officer says to Inspector Waziri in OCTOBER 1, it is “your country now.”

Make that continent.