Architectural History Matters: Sultan Hassan + Rifa`i Mosques

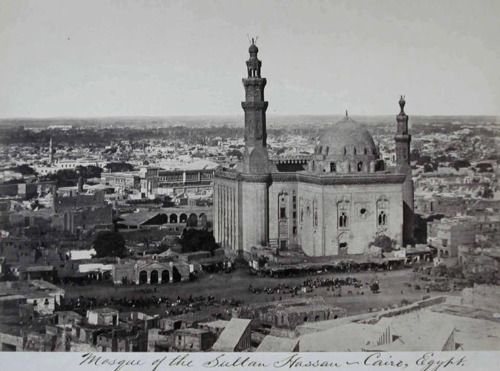

At first glance the two mosques pictured above appear to belong to the same historical era. The Sultan Hassan Mosque (left) and al-Rifa`i Mosque (right) are two of Cairo’s most important monuments and they stand at one of Cairo’s most important and oldest squares at the foot of the Citadel. The two buildings compliment each other in proportion, material, orientation and although they stand out in their urban context because of their immense scale, they are also harmonious with the context, grand but not oppressive, monumental yet contextual. The pedestrian street between the two buildings is an extension of Mohamed Ali Street (شارع القلعة), and it is one of Cairo’s most impressive urban spaces to occupy. The two buildings frame the Citadel and Mohamed Ali Mosque to one side and looking the other way one’s eye is directed towards what was once one of Cairo’s most important modern streets cutting through the dense urban fabric of historic Cairo towards Attaba and Cairo’s 19th century extension. The street is the work of 19th century urbanism cutting through and negotiating the existing ancient city. The two mosques too are a negotiation between ancient and modern. Between the completion date of Sultan Hassan Mosque and the completion date of Rifai` Mosque are 551 years, but you wouldn’t know it by looking at them in passing.

Hussein Pasha Fahmy was commissioned in 1869 by Khedive Ismail’s mother to build a dynastic mosque in the place of a small shrine for al-Rifa`i. He died during construction and work completely stopped in 1880. In 1905 Helmi Pasha commissioned Max Herz who was in charge of the Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l’Art Arabe, to complete the structure. The mosque was finished in 1912.

The Comité is an egyptian organization (despite its French name), established in 1881 by Khedive Tawfiq for the documentation and preservation of Islamic and Coptic monuments. This entailed a careful study of historic architecture. The organization was part of the Awqaf system and it continued to function until it was formally dissolved in 1961.

There are many reasons why Rifa`i Mosque looks the way it does, reasons that have to do with politics and history (The choice by the royal family of Mamluk rather than the typical Ottoman style). But history, specifically architectural history, was necessary before building the new mosque. The architects (Hussein Fahmy, Max Herz or his assistant Carlo Virgilio Silvagni) had to fully understand the architecture of the past before creating something new, or reviving something old (that was the work of the Comité). Although from the square or the street the two buildings are in harmony with one another, they are fundamentally different buildings in plan and section, ornament and experience. While Sultan Hassan is the quintessential Mamluk Mosque and Madrassa, al-Rifa`i is quintessentially late 19th century Egyptian: it contains elements of historic architecture, the plan is a balanced Beaux-Arts plan and the decorations inside bring together the eclectic taste of the times. This is perhaps contextual architecture at its best at this scale.

Al-Rifa`i doesn’t reflect a lack of knowledge with Cairo’s cumulative architectural heritage. It does not reflect an architectural identity crisis. It does not try to be something it isn’t or import what doesn’t belong. Instead the mosque reflects a thorough understanding of Cairo’s architectural history and a serious academic engagement with that heritage in the building of a new monument. The builders were not enslaved by that history nor did they try to replicate or uncreatively reconstruct what they understood to be “authentic.” To the contrary, the mosque is both innovative and contextual.

Architectural history is nearly absent from today’s practice and education in Cairo, which is one of the main reasons for the current architectural and urban planning crisis. The history of architecture must be fully understood in order to restore old monuments, revive a historical style or in order to rebel completely against the past.

*Images below: 1. King Farouk leaving Rifa`i Mosque, 2. Sultan Hassan Mosque in the 1860s before the construction of al-Rifa`i Mosque, 3. Half-built Rifa`i mosque during construction.

6 notes

cairobserver posted this