Walking, harassment and the urban geography of two Maadis

By Nadine Hafez

In Cairo it often feels like you have no choice when it comes to your transportation: You’re either driving and stuck in traffic, or you’re in a cab and both you and the driver are stuck in traffic, or you take the metro and you’re stuck in a whole other kind of traffic. So for someone like myself who likes to walk, I try to seize any opportunity that presents itself to walk the streets of Cairo. I live in Maadi and study in Cairo University. So my route back home is usually Cairo University to Maadi by metro and then home inside Maadi a pied.

But walking in Cairo doesn’t come without its challenges. Every girl and woman in Cairo faces the reality of sexual harassment – primarily verbal – on a daily basis and Maadi is no exception. During my walks, however, I’ve come to notice an interesting phenomenon: The harassment starts and stops at a certain point in Maadi; a street that acts like a switch that turns the harassment on and off.

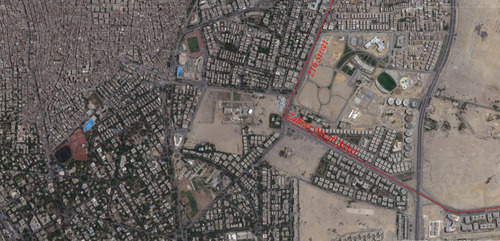

I’ll try to first quickly sketch a pedestrian map of my walks and a basic structure of Maadi. Maadi is divided into two camps, Old Maadi and New Maadi. We usually take Road 9 as the starting point. The other end of Maadi would extend a little beyond Nasr Street. The fine line that separates between the two is Road 216: Road 9 to Road 216 is Old Maadi, Road 216 onwards is New Maadi. On my walks, I cross the entirety of Old Maadi from Road 9 – where the Sakant metro station is – to the end of Road 216 and turn right onto Al Zahraa road to head home. It’s at that specific turn that the sexual harassment begins.

[The fine line dividing old and new Maadi, shown above is the intersection of 216 Street and al-Zahraa Road.]

It seems that there is a relation between the architecture of the different parts of Maadi and the sexual harassment we’re subjected to and it runs deeper than just sexual harassment. Old Maadi is a comfortable space i.e. it’s comprised of low residential buildings and villas as well as many foreign embassies between which the spaces are generous; enough to host a garage, a backyard and ample distance to avoid any trespassing on the next door neighbor’s privacy or peace of mind. In there, property is respected by all, because the boundaries of each individual’s or family’s property are very clear. New Maadi on the other hand is much like many other areas in Cairo: condensed residential buildings, scores of stories high and barely any space for parking let alone backyards. The lines that separate my property from yours are very blurry: any one can park in this spot on this street or that in front of any building any time of day.

In reference to sexual harassment, my theory is that one of the factors contributing to its widespread nature is a certain understanding in a large sector of the population’s mentalities that women are property not citizens, i.e. their bodies are public property. It’s why certain people give themselves the right to trespass my right to walk the streets in dignity; his right is superior to mine given the difference in citizenship status.

Accordingly, where property is respected so am I and vice versa. Architecture doesn’t only reflect our decisions and social design; it is also sometimes reflected in our behavior because it’s a two way relationship.

This phenomenon is therefore not a reflection of the relationship between male and female citizens in Cairo only, but also of the relationship between citizens and property and consequently between them and the city. We suffer from something I call valueless ownership. We don’t care to preserve our property as much as we do to maximize the benefits and pleasures obtained from them. Despite the fact that property would need to be preserved in order for you to benefit from it, we’ve reached a point of depreciation of value and a focus on ownership that is blind to anything else.

We thus treat the space of the city we navigate on a daily basis with its function only in mind: it’s no more than a geographical roadmap for citizens to reach desired destinations in order to enhance certain relationships, or get to work and support ourselves financially, or visit the mosque or church or any other ends, the city is always the means, almost never the end in and of itself.

Perhaps if the city does become an end in and of itself, if we care to preserve it as our public property and manage to draw the clear lines between what is public and the private property of every individual in Cairo the women and men of Cairo will have safer, better streets to walk.

31 notes

averil-of-fairlea liked this

laylainwonderland reblogged this from cairobserver

thoughtspapersballons liked this

poisonouscherries liked this

poisonouscherries liked this driedfruits liked this

jsuslovesyou liked this

cundtcake liked this

cundtcake liked this kaash liked this

hummussexual liked this

urbanalysis reblogged this from cairobserver

thebaboonshack reblogged this from cairobserver

thebaboonshack liked this

cairobserver posted this