As I was reading through the healthcare opinion earlier, this statement from Justice Roberts’ Commerce Clause analysis caught my eye (pg. 26):

The Commerce Clause is not a general license to regulate an individual from cradle to grave, simply because he will predictably engage in particular transactions. Any police power to regulate individuals as such, as opposed to their activities, remains vested in the States.

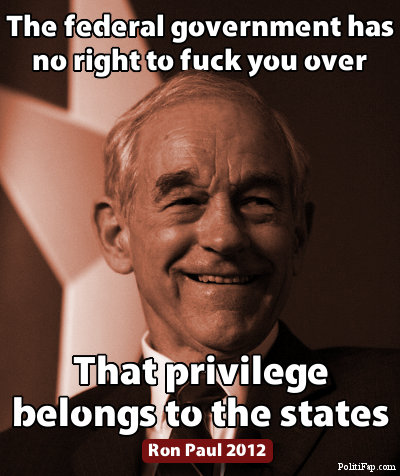

I couldn’t help but chuckle when I read this, as it made me think of the following photo:

There are logical, sound, reasonable arguments for reserving certain powers to state governments rather than to the federal government. But tyranny by any other name is tyranny nonetheless. Yes, one of the advantages of federalism is that if you don’t like the laws of a particular state, you can move. But the same argument applies to the country writ large. So too does the obvious objection to the former: most people can’t simply pick up and move when things get bad. Human beings tend to develop localized networks of social, economic, professional, and emotional support that they rely on in their daily lives in order to thrive. You can’t bring those networks with you when you leave a state. There’s always significant sacrifices to be made, not least of which is the loss of familiarity with your surroundings, forced distance from loved ones, and the professional relationships you may be forced to leave behind.

The police power of the states, in my opinion, is a far broader and scarier thing than the Commerce Clause ever has been or ever will be. And unlike the federal constitution, state constitutions are fairly easy to amend. While this makes onerous provisions easier to abolish, it also makes rights and guarantees much less resilient. This is both the blessing and curse of decentralized polities.

It should also not be forgotten that at many points in history, it has been the federal constitution, enforced by the federal government, which has prevented American citizens from suffering at the hands of state lawmakers. The darkest periods in our nation’s history, viz. Slavery and Jim Crow, were justified by the police power of the states. If you review the arguments of state attorneys general in old cases, you find that discrimination against women was justified by the police power of the states. You find that anti-miscegenation laws were justified by the police power of the states. You find that discrimination against gays was and is justified by the police power of the states. You find that onerous restrictions on expression and free speech have been justified by the police power of the states. The breath of state laws that imposed onerous restrictions upon unpopular classes of citizens is long and painful to apprehend; as are the multifarious and unfortunate indignities visited upon various marginalized groups of people throughout American history.

Yet in virtually every case, it was the federal constitution, and in many cases the federal government, that helped end these various forms of oppression. Local state governments with popular support legislated against unpopular minorities, and federal power stopped them. That could not have happened if we held up the Tenth Amendment and the doctrine of enumerated powers as the supreme guideposts of constitutional interpretation.

The true benefit of federalism is that it creates a system of dialectical power-sharing. The states are granted the purview to serve as “laboratories of democracy” to come up with novel ways to solve problems. But when a purely local solution cannot be efficiently implemented in isolation from the rest of the country, the federal government has the scope of jurisdiction to address it. The founders recognized that not every problem was within the power of an individual state to solve. That is why they gave the federal government the ability to regulate interstate commerce in the first place. It is also why the founders gave the federal government the authority to print money, to regulate immigration policy, and to have the final word in international relations. They wanted the federal government to be able to craft policy in areas where economic and national security realities would render a localized solution ineffective. As our nation’s history evolved, and the Fourteenth Amendment was passed, the federal government’s power to regulate areas of national concern became a check on state power, in addition to addressing matters of national concern. This allows the federal government to protect people when states abuse the obscenely broad authority that the police power inherently grants them. It also allows the federal government to protect people where the states have failed to do so.

Conversely, when it is the federal government fails to act, states can implement their own laws to protect the rights of their citizens. We see this exemplified in the relatively recent trend of state legislative enactments legalizing same-sex marriage. We also see it in the criminal justice system, where certain states have rejected the Supreme Court’s rather loose interpretation of the Fourth Amendment’s Search and Seizure Clause, and used state constitutions and statutes to protect their citizens from unreasonable intrusions by law enforcement officials. Yet here again, the federal government fills a necessary gap: 42 USC § 1983 provides a civil remedy against state government actors who violate their constitutional rights. This remedy abrogates the sovereign immunity of the states granted by the Eleventh Amendment. Where the states refuse to protect citizens from lawless government actors, the federal government steps in to protect them, and vice versa. At least that’s the way it’s supposed to work.

It is this simultaneously antagonistic and symbiotic relationship that creates a healthy federalism. It is the same federalism that grants the federal government the power to come up with a national solution to a problem like healthcare, where our nation’s woes are shared across state lines, and consequently, do not easily admit of a local solution. Keep in mind that this is not an argument about private v. public sector. It is about state government v. federal government. And to the extent that the former retains a broad an untamed police power, I am more than happy to see the federal government entertain a broad authority under the Commerce Clause. And I think this is also the reason why previous Supreme Courts, throughout history, have interpreted the Commerce Clause broadly. They were able to see that not every problem can be solved at the local level. And though government is by definition an imperfect institution, that imperfection is manifest in ill-advised state law as much as it is in federal law.

And so I disagree with Roberts’ Commerce Clause analysis. I think the activity/inactivity distinction is vacuous and unprincipled; many a constitutionally enacted law places affirmative obligations on people to act, at a cost to themselves, where they otherwise wouldn’t. But more importantly, I think proponents of Roberts’ interpretation of the Commerce Clause fail to give due consideration to the much broader police power of the states, which Roberts has declared perfectly encompasses the ability to regulate inactivity. This may Give Mitt Romney a colorable premise for distinguishing his Massachusetts healthcare reforms from the Affordable Care Act. But it does not give me much comfort to know that the state governments may oppress me in ways the federal government is restrained from doing.

What might I do to avoid this tyranny? As a New Yorker, I suppose I could always move to Massachusetts. But after being in Springfield during the lead-up to the 2004 World Series, I don’t think I could tolerate the oppression of Red Sox fans, who I must admit I now fear more than the states’ police power. But given the Red Sox’ track record since then, perhaps I shouldn’t be too worried. Perhaps.

kileyrae liked this

mynameisntsir reblogged this from letterstomycountry

abcsoupdot liked this

nickthejam liked this

ishqoinqilab-blog reblogged this from letterstomycountry and added:

This is an interesting and enlightening read, for anyone wondering about Roberts’ opposition to using the commerce...

pulledteeth2 liked this

pulledteeth2 liked this parallaxative-blog liked this

acontemporaryliberal liked this

acontemporaryliberal liked this kohenari liked this

excitablehonky liked this

rweroom liked this

aestheticofhunger reblogged this from letterstomycountry

letterstomycountry posted this