[Antwerp, Belgium/July 24-31, 2011] By Ari Ernesto Purnama

“There really is no such thing as art. There are only artists”—E.H. Gombrich

Zomerfilmcollege (Dutch/Flemish for Summer Film College) has been an amazing experience. What more can you ask when you have cinephiles, filmmakers, film scholars, film enthusiasts, theatre owners and avid movie goers in general converge for a week full of lectures, discussions, informal conversations about films? As David Bordwell put it, this is basically a “film summer camp”—more than anything else. Actually, there’s more to this as I look back on that whole week. Never had I been so enthused by people’s passion for films and the lively discussions that went with it. With participants ranging from a 17 year old to a 70 year old, this fact blew me away as I am pondering about what drove them to join this fully intensive summer course. Yet, the answer is right there all along: appreciation for the arts of cinema.

Starting the day at 9am with a lecture, film screenings and Q&A sessions to follow that, and finish roughly around midnight every day in that week was a life of its own. So, blossoming new friendships, new knowledge of unknown films and directors, and scholarly camaraderie were among the things that I find invaluable from this event. It was a shot in the arm. Not to mention the screening of more than 30 films in 35mm prints really gave me that immersive experience more so than watching them on DVDs (of course, you might say). Call me a techno-geek, but watching a great deal of 1940s monochromatic Hollywood films on 35mm and a huge silver screen really make a difference!

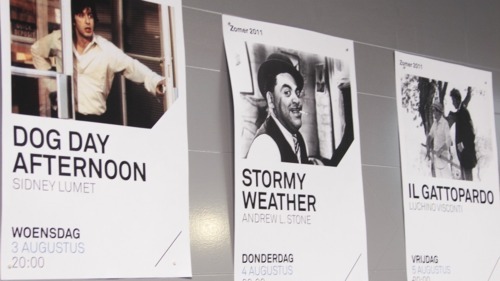

Zomerfilmcollege is a biennial event initiated by the Flemish Service for Film Culture (VDFC) in Brussel, Belgium. The program has started already in the 1970s—as one participant shared his memories with me from those days over a coffee break (thanks Marc!). It is normally held in Brugge, but this year Antwerp hosts the program for the whole week. Antwerp Cinema Zuid acts as the facilitator for the daily lectures and screenings. One of the things I love about Cinema Zuid is their programming. Although I didn’t get the chance to see one of them, but having Otto e Mezzo and Dog Day Afternoon in their monthly-themed program sounds very enticing. If I happened to reside in Antwerp, I wouldn’t mind going to Cinema Zuid several times a week just to see the classic masterpieces, again, on their 35mm prints. Heavenly.

One of the main speakers at this year’s Zomerfilmcollege, and has been for many years, is no other than Professor Emeritus David Bordwell. Despite his retirement years as an academic staff from the university, Bordwell is more active than ever in film research, film festivals, conferences and other cine-related gatherings, in addition to his and his wife Kristin’s prolific activities on the blogosphere [according to their preface for Minding Movies (2011) the blog has 80.000 returning visitors annually] Every other year he attends this film summer course and gives short courses as a tribute to the Cinematek in Brussels to which he indebted with for many years of his research activities. This time around, his topic throughout this college revolves around storytelling experimentation in Hollywood in 1940s, hence the title “Dark Passages: Storytelling Strategies in 1940s Hollywood.”

As an entrée, on our first day, Bordwell presented a talk which I found really fascinating as a student of style and film aesthetics in general. The title was “Seeking and Seeing: Lessons from E.H. Gombrich.” Not only have I been an admirer of Gombrich’s works on art history and Bordwell’s transposition of Gombrich’s “problem-solution” model to historicizing film style, importing Gombrich’s ideas to study one particular period style—1940s Hollywood movies— sounds promising. For the most part, it confirms most of the things I believe about studying the cinematic arts, particularly in respect to visual style. As his [Gombrich’s] audacious statement expresses that ‘there is no such thing as art, there are only artists,’ Bordwell explains that in this sense Gombrich’s emphasis in studying art history is to focus on crafts. Consequently, Gombrich concentrates on the idea of visual artists as ‘image-makers.’ They are active agents working in a tradition in particular historical circumstances. They are driven by tasks, and believe or not, competition comes into play when artists seek to revise and push the convention of a particular strand of artistic tradition.

A curious feature of Gombrich’s conceptual thought is that it brings the study of artistic history to a pragmatic and concrete level. Granted, it does not subscribe to a Hegellian model of art and artists as floating spirits waiting to descend at particular junctures in human history. So applying this to 1940s Hollywood cinema, Bordwell is interested in examining, for instance, why there are no high-key crime films in 1940s Hollywood. “You may argue that Laura (Otto Preminger, 1944) is, but we can discuss this,” Bordwell remarks. He continues,“But basically there is a clear division in Hollywood cinematographers in the 1930s and 1940s that [prescribe] certain subjects require certain types of lighting.” The high-contrast visual gradation driven by the low-key chiaroscuro lighting style was iconified in the 1940s, he explains, “when you have a crime scene, that isn’t a comic one, that’s how you light it. If you have a comic or romantic scene, that’s how you light it,” describing the narrowing down of options for cinematographers at the time. “There is a certain amount of constraint by virtue of a genre that dictates what kinds of images you can have.” And then Bordwell reiterates his research question, “But what happened in the ‘40s then?” One thing that he pursued in this Zomerfilcollege is to explore one plausible explanation to this inquiry: “In 1940s, they just start making more and more crime films. Or at least the crime film changes to the point where it became so much more a dignified drama that it becomes more important in the genre hierarchy.” This hypothesis was further investigated throughout the week.

Interestingly, we were participating in this research quite interactively in a model that to me seems very engaging. So we normally watched the film in the morning, from Hithcock’s Suspicion to Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai to lesser known ones that still attract closer inspection as case studies such as Crossfire (Edward Dmytryck, 1947) and Letter to Three Wives (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1949), and we would have a discussion afterward. Bordwell will deliver a lecture based on the screened film the following morning. Therefore, by doing so, we were all sailing together with Bordwell on a scholarly ship that he manoeuvred, so to speak, but our feedback and commentaries were channelled back into challenging the hypothesis or augment the findings, albeit moderately, as so much of the discussions tend to revolve around plot postulations, e.g. “what about the moment in Laura where Waldo could actually see the incoming detective while he was actually in the bath tub?” Although I don’t particularly mind talking about what happens in the narrative, when the air of debate circulates around interpretive speculations, it can be rather distracting. Nevertheless, and this is where I have to say a few things about Bordwell’s didactic and oratory virtuosity, I learned a lot from just observing the interaction. Never had I found a speaker who could make the audience so attuned for almost two hours without making them falling asleep or yawning, at least to me. Bordwell encapsulates my idea of a ‘great thinker-great communicator’ type of scholar who presents his ideas and substantiations in a clear and no-nonsense manner and yet manages to slip in erudite humour that would make us chuckle and laugh. Moreover, his awe-inspiring pedagogic approach was exhibited in his handling of the Q&A sessions where he could facilitate a lively discussion and more important to navigate question(s) or comments that may not necessarily on point and perhaps diverging from the core issues in a way that would not belittle the intention of the commentator(s). This mastery in handling a formal forum, to me, is an inspirational thing for any aspiring film scholars, lecturers or educators in general.

There are many more lines of inquiry and ideas that were explored in this 7-day-event, however, I won’t be able to cover all of this at once. So, to conclude this short notes, let me outline some of the findings that Bordwell offers in his lectures which I think is illuminating in regards to storytelling mechanics of the 1940s Hollywood cinema:

The complex and often convoluted storytelling strategies that we associate 1940s film noir with are actually broader than the hard-boiled detective fictions. They are evident in quite a wide range of dramatic and comedic genres. Does this notion challenge and problematize the noir status as a genre further?

*I personally thank Dr. Miklós Kiss who made it possible and also to have introduced me to this amazing event.

**For Carola van Dijk and Steven Willemsen, thank you for the awesome late-night-talks and the scholarly camaraderie. Couldn’t ask for better companies.

Highlights of Films screened at the Zomerfilmcollege 2011:

PATHER PANCHALI- Satyajit Ray, India 1955, 122’

MIRACOLO a MILANO-Vittorio de Sica, Italy 1951, 100’

THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS - Clarence Brown, Maurice Tourneur, USA 1920, 75’

EL ESPIRITU DE LA COLMENA - Victor Erice, Spanje 1973, 99’

DU SKAL AERE DIN HUSTRU - Carl Theodor Dreyer, Denemarken, 1925, 107’

CARAVAGGIO - Derek Jarman, UK, 1986, 92’

ARSENAL - Alexander Dovzhenko, USSR, 1929, 87’

STAGE FRIGHT - Alfred Hitchcock, UK,1950, 106’

DAISY KENYON - Otto Preminger, USA 1947, 99’

HOW GREEN WAS MY VALLEY - John Ford, USA 1941, 118’

LAURA - Otto Preminger, USA, 1944, 88’

THE KILLERS - Robert Siodmak, USA 1946, 102’

SAYAT NOVA - Sergei Paradzhanov, USSR 1971, 73’

LETTER TO 3 WIVES - Joseph L. Mankiewicz, USA 1948, 103’

LADY FROM SHANGHAI - Orson Welles, USA 1947, 87’

SUSPICION - Alfred Hitchcock, USA, 1941, 100’