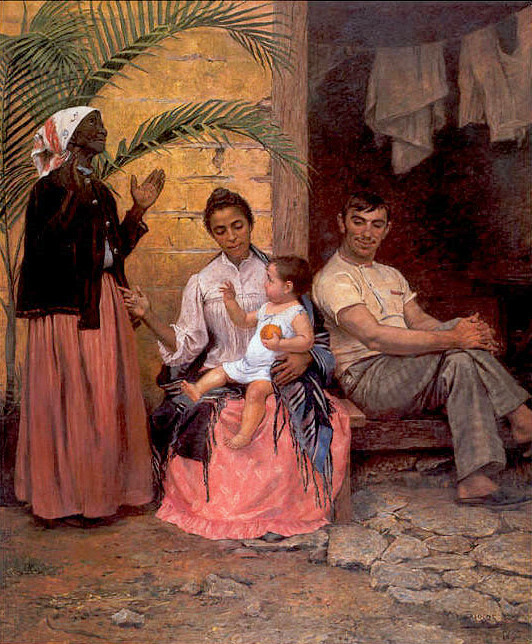

Modesto Brocos y Gómes, 1895, A Redenção de Cam (The Redemption of Ham)

In the years leading up to Lula’s push for stronger political and economic ties with African countries, the dialogue on race and African identity underwent substantial changes. In the 1990s, President Fernando Henrique Cardoso was not only the first president to publicly acknowledge that racism existed in Brazil, but he was also the first president to acknowledge that he had a “foot in the kitchen” – a reference to his own African heritage. Such statements flew in the face of decades of the marginalization of African identity.

In the aftermath of the abolition of slavery in 1888, Republican-era (1889-1930) Brazilian elites believed that the newly freed Afro-Brazilian population, which was assumed to have retained its “backward” culture, would impede Brazil from taking its place among the developed industrial nations of the world. At the same time, theories of scientific racism were infiltrating Brazil, and Brazilian elites sought to “whiten” the country’s population – an ideology best captured in Modesto Brocos y Gómes’ 1895 painting A Redenção de Cam (The Redemption of Ham – from the Bible’s Book of Genesis). This painting depicted embranqueamento (whitening) – the ideal that through European immigration and miscegenation, every Brazilian generation would become whiter.

Cardoso’s statements also flew in the face of the subsequent promotion of the myth of racial democracy, which originated with the 1933 publication of Gilberto Freyre’s The Masters and the Slaves. This book asserted that the institution of slavery encouraged racial tolerance and intermingling so that Brazilians inherently had no racial prejudice, contrary to what the author had observed in Europe, the United States and Africa. Freyre emphasized how Brazil’s three races contributed to formation of the nation, giving them a reason to feel proud of their unique, ethnically mixed tropical civilization. Brazil’s embrace of this ideology promoted the notion that all Brazilians lived in racial harmony, and that any discrimination Afro-Brazilians suffered was a function of social class, not of race. This has historically deprived several Afro-Brazilian civil rights movements of their solitary target for mobilization.

- via

ddarkffeminine reblogged this from iandeleonarts

peopleofthediaspora reblogged this from iandeleonarts

peopleofthediaspora liked this

chemman99 reblogged this from iandeleonarts

iandeleonarts posted this

iandeleonarts posted this