I was pleased to learn that both of my proposals to the Society for Cinema and Media Studies were accepted for this year’s conference in Seattle. Both proposals were meta-scholarly - aimed at addressing the practices and infrastructures by which contemporary media scholarship is evolving - as opposed to focusing on examples of that evolution.

My real goal was to show off the authoring platforms to which I have been devoted for the past several years: Critical Commons, Scalar and the Difference Analyzer, which is slated for beta release shortly before the conference. These platforms are also deeply integrated on conceptual and technical levels with my Technologies of Cinema project and SCMS seemed like the ideal venue in which to situate this work within a broader landscape of evolving tools and protocols for reimagining media studies at large.

A surprising proliferation of analytical tools has emerged from various corners of academia and fan culture in recent years. Several of these projects, in fact, have been launched by pseudonymous bloggers or communities of contributors who very well may not regard themselves as doing anything related to media scholarship at all - a phenomenon that I find interesting in itself.

In an attempt to understand what is happening, I will divide these practices into three rough categories:

- Video essays

- Fan distillations

- Computational engines

Video Essays

The most formally straightforward mode of mediated analysis is the video essay. We may trace the roots of this practice back to American essayists and European New Wave filmmakers such as Jonas Mekas and Chris Marker, though today’s legacy is more clearly linked with the 1990s compilation essay genre inaugurated by Mark Rappaport (From the Journals of Jean Seberg, Rock Hudson’s Home Movies) and Thom Andersen (Red Hollywood, Los Angeles Plays Itself).

More recently, Indiewire’s PressPlay, Catherine Grant’s Film Studies For Free and the peer-reviewed SCMS journal InTransition have provided spaces for videographic scholarship to flourish as an increasingly viable mode of critical analysis. Kirby Ferguson’s Everything is a Remix is additionally interesting for his prolific use of split screens to illustrate formal resonances among genre films.

Building on Lawrence Lessig’s now decade-old assertion that “creativity always builds on the past,” Ferguson has done a TED talk and a series of short, polished remix videos illustrating an identical point across the fields of music, cinema and technology design. These seem to me to be a useful but readily understandable genre of emerging scholarship.

Fan distillations

Somewhat more enigmatic is the recent proliferation of fan sites and shared online spaces that offer visual interpretations of movies through radically distilled forms. These include Movies in Frames (tagline: “One film - four frames. That’s it.”) and 9 Film Frames, which launched in March 2013, attempting to “showcase a film by using only 9 of its frames.” Despite minor presentational differences (Movies in Frames presents its four frames arrayed vertically; while 9 Film Frames opts for 3x3 grid presentation), each of these may be understood as a visual corollary to the radical economy of microblogging, with the cinematic equivalent of 4-9 frames offering a rough approximation of the 140 character limit of Twitter.

All of this suggests a desire to distill time-based experience into a crystalline, easily digested form, which nonetheless revels in the profuse aesthetic pleasures of montage. Indeed, the lurid color schemes of Wong Kar-wai or Wes Anderson are arguably better appreciated when arrested in time, even though the time-based pleasures of performance and narrative are largely stripped away.

A form that preserves the pleasures of time, while sharing the core mechanic of distillation is that of the supercut. A longstanding memetic genre of online video, many supercuts satisfy themselves with dramatically or humorously illustrating a single visual trope or cinematic cliché: the mirror scare or loss of cell phone service in horror films, for example, or three point landings in action films. Included in this genre are the “every ____ in ____” supercuts. Every drink in Mad Men; Every “dude” in Lost; and so on. To this easily trivialized subgenre, I would add the genuinely incisive political critique implied by the multiple, dynamic split-screens of 236.com’s Synchronized Presidential Debating, which reveals the overly scripted nature of contemporary political campaigning.

While supercut auteurs such as Duncan Robson continue to brilliantly expand and refine the genre online, supercuts were quietly elevated to the status of art in 2009 with Natalie Bookchin’s multi-channel video installation Mass Ornament and Christian Marclay’s 24-hour installation The Clock (2011).

Both of these interestingly share a computational (read: encyclopedic) sensibility but attack their data sets (all of YouTube and all of cinema history, respectively) with sheer human will rather than computer algorithms). Few others have surpassed the brilliance of the video/remix artist who goes by the name Kogonada.

Like many working in a fundamentally visual register, Kogonada’s prolific body of supercuts focuses on formal similarities (POV shots in Breaking Bad; one-point perspective in Kubrick; passageways in Ozu, and more). Using exquisitely edited montage, he creates sequences that lyrically resonate with the original works themselves. What separates Kogonada’s work from many other supercuts is its resistance to any discernible algorithmic logic in the editing of scenes. Faced with an overwhelming accumulation of raw materials, remixers often resort to a deterministic structure based on chronology or category, essentially treating editing as an extension of the process of asset acquisition. I do not mean to necessarily privilege human over machine logic in the assembly of these sequences, but I would argue that the type of algorithmic pleasure - derived from recognizing the underlying logic of a dynamic system - delivered by Kogonada is available to viewers in either mode, without arbitrarily fetishizing the computational.

Departing even further from the representational capacity of the films themselves, Movie Bar Code reduces a film’s color palette to an abstracted bar averaging the tonal range of each frame over the course of the film. The resulting color spectra (which indeed resemble spectrographic images) provide a snapshot of a film’s production design, but say precious little about the film’s actual content. Still, Movie Bar Code suggests a provocative, if overly literal conversion of cinema’s time-based complexity into a single dimension represented by color data (seen here is Richard Sarafian’s 1971 road movie classic Vanishing Point).

Computational engines

I have been struggling for several years to articulate my lack of excitement about the work that Lev Manovich and others (many of whom I also know well and respect highly) have been doing in the area known as cultural analytics.

At first glance, cultural analytics seems to be doing everything right. They have undertaken consideration of a wide variety of easily neglected cultural artifacts and data sets: old and new, high and low, commercial and experimental. Some of their analytical strategies also resonate with the basic structure of the Difference Analyzer - multiple juxtapositions, split screens, dynamic visualizations, the creation and free distribution of tools and protocols, etc. The lab’s inversion of traditional scientific hierarchies privileging quantitative over qualitative data allows humanities researchers a seat at the table of big data analysis, bringing long-neglected questions of culture and visuality under consideration. All of these things should make me admire and respect the transformative potentials of this project.

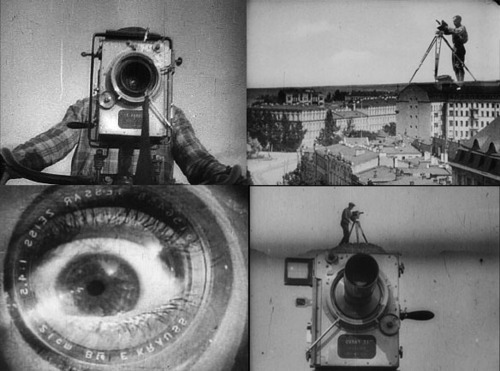

But instead, I find myself mired in formalist patterns and aesthetic pleasures - neither of which I am fundamentally opposed to, except when they stand in for depth of insight into cultural practices and significance. Cultural analytics also promises to offer access to new ways of seeing - hence the appropriateness of Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera as the provider of one data set. Vertov’s kino eye sought precisely the kind of hybrid human-machine vision and ubiquitous capture that still fascinates consumer electronics nearly a century later - an intelligent, mobile, mechanical agent for re-visioning the documentary world.

When Vertov grafts his brother’s camera onto images of the human body and brings it to life through stop-motion animation, it suggests agency and autonomy in the apparatus of cinema itself - a prescient image of contemporary machine vision and consumer sousveillance. But Vertov’s intervention in the emerging languages and technologies of cinema was deeply enmeshed in a politics of seeing that starkly contrasted the “puppet theater” that he accused Eisenstein of practicing. The reduction of Vertov’s revolutionary documentarism to machine-readable formal properties (closeups of faces, first and last frames of every shot, etc.) evacuates the politics from Vertov’s project, while adding little to our ability to “see” the film and its historical impact.

In this regard, I would compare some of these experiments with Mark Sample’s Godard Generator, a witty engine that recombines tropes from Godard’s cinematic oeuvre into playful abstracts. Like Sample’s project, cultural analytics may serve to reinforce and reward existing knowledge, suggesting superficially pleasurable extensions of that knowledge, but it would be difficult to argue that it breaks new critical ground in our understanding.

The frequent delivery and reception of cultural analytics projects in an art context has also seemingly lowered expectations for the “analytic” part of the project in favor of the “cultural.” When displayed at full-scale, this work is indeed dazzling - an appropriate term, as this word’s literal meaning denotes temporary blindness - and as complex insights elude the viewer, one may always fall back on the pleasures of form. In a gallery context, cultural analytics are arguably freed from the expectations of rigor that attend a more explicitly scholarly context. The work is open to interpretation and discovery of the viewer’s own choosing, but at what cost?

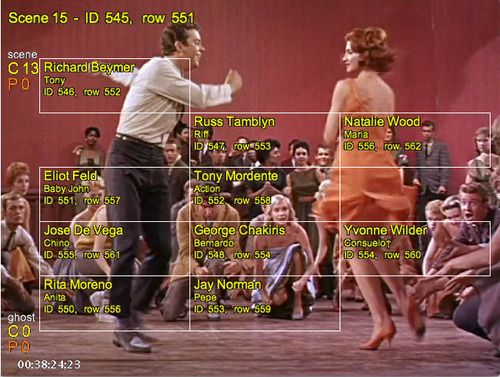

All of these reservations aside, I confess to being sympathetic with work that aspires to analyze, on a grand scale, both small and large patterns of representation across huge data sets. A couple of years ago, with Michael Naimark and Joshua McVeigh-Schultz, I worked on a project called MovieTagger, which sought to “richly parse and tag every movie ever made.” For this project, the entirety of cinema history was reconceived as one big database that could be atomized and addressed down to the level of the frame. This was an admittedly daunting task, given the size and diversity of our data set, but this is the type of thing that Naimark has repeatedly shown to be limited not by computational capacity but the constraints we place on our own imagination. In a few more years, the technology to perform analysis on such a scale will be trivial and our ability to imagine what we can do with it will once again be playing catch up. MovieTagger was an attempt to get ahead of technology on a conceptual level and derive an intellectual framework that could drive technology development, rather than the other way around.

Our industry partner who funded the undertaking had developed a robust, time-based system for addressing and annotating frames of film and TV content. Initially, this was used primarily for purposes of tracking elements such as product placement, actor screen time, and other foundational metadata of interest to marketers and industry bean counters. The company was well aware that broader potentials existed for such a system to attribute rich, time-based metadata to media content but they were not sure what types of annotation were most productive to pursue.

From the outset of the project, we made it a primary goal to position MovieTagger in direct opposition to the formalism of cultural analytics. Our tagging schemes thus focused on a variety of critical dimensions that might ordinarily be thought to be indigestible by a computational frame-tracking system: race, gender, violence, technological representation, ideologies of parenting, regionalism, etc.

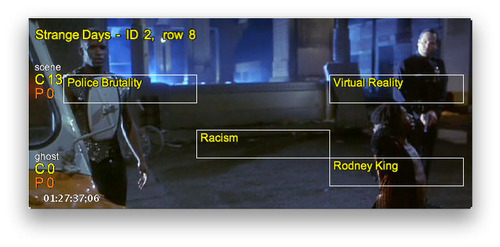

Various scholars from USC and elsewhere were enlisted to define critical parameters that would allow MovieTagger to supplement analysis of issues of concern to media and cultural historians that deliberately resisted the bounds of formalism. After a highly productive year of work resulting in multiple presentations and publications, our industry partner was acquired by another company (along with the tagging platform on which the system depended), unceremoniously leaving MovieTagger in its pre-release alpha stage at the proof-of-concept altar. Although never consummated publicly, the handful of analytic projects - mine involved the analysis of racism, VR technology and historical resonances with the Rodney King beating in Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days (1995) - undertaken in collaboration with the MovieTagger apparatus demonstrated (with a minuscule fraction of the resources that have been devoted to cultural analytics) the ease with which computational analysis need not limit itself to formalist concerns.

As my collaborator, Chandler McWilliams, and I move forward on the Difference Analyzer, we have set a similar challenge for ourselves, to architect the platform as an analytical engine that invites - but is adamantly not limited by - the allure of formal analysis. Nearly identical scenes appearing in films separated by decades of film history, for example, make for an enticing collage as this juxtaposition of Sirk’s Written on the Wind (1956) and The Rum Diary (2011) illustrates. But the primary analytical affordances of the Analyzer must aspire to something more than highlighting these formal resonances. My hope is that the analytical conjunction of multiplicity and synchronization within a natively time-based, multi-channel critical environment will serve as an engine for asking rather than necessarily answering questions of cinematic meaning. The scale and aspirations for this project do not come close to those promised by cultural analytics, but my hope is that we will successfully model new modes of questioning and seeing within media studies. Such an engine, unshackled by the limits of formalism, might still capture the dynamic pleasures of performance and display as fundamental components not of cultural analytics but of cultural analysis.