Rejection, Social Justice and the Little Lies We Tell Ourselves: An Interview with Pearl Cleage

(Via Shelf Awareness)

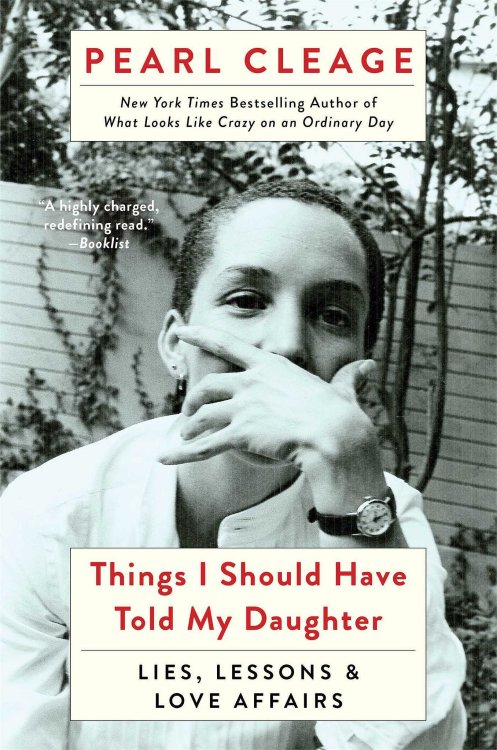

In Things I Should Have Told My Daughter Pearl Cleage shares unvarnished selections from two decades of her journals, starting in 1970. They reveal a young woman sorting out her feelings about the life she has and the one she wants. It’s as though she is confiding in us as she struggles with her career and marriage, her desire to write and above all, her need to be authentic, all filtered through her awareness of racism and feminism.

Cleage was raised in the public eye in a family committed to social justice. Her father was a prominent civil rights leader and pastor. He founded the Shrine of the Black Madonna Church and Cultural Center, which is still committed to social justice. Her mother was a teacher. In 1969, she married Michael Lomax, an Atlanta politician and, later, president of the United Negro College Fund. They divorced in 1979; she remarried in 1994. Lomax is the father of Cleage’s daughter, Deignan Njeri, who years later recommended that Cleage burn her journals because the facts of her life were already public and the emotions behind them messy. She didn’t; instead, she has published excerpts in this forthright and revealing memoir. In 2011, she placed more than 50 boxes of her journals and other papers with Emory University’s Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library.

You’re a well-known novelist and also a celebrated playwright–you won five AUDELCO Awards for Outstanding Achievement Off-Broadway in 1983. How are the two forms different?

The theater is collaborative. Once the play is written, you become part of a band of people all working to bring it to the audience–the actors and stagehands and director and scene designers. I like that process. You write a novel by yourself, and reading it is a solitary experience. The content is not necessarily dictated by the form. I wrote my first novel, What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary Day, because it was an idea that would never work as a play; it had too many settings and could never fit into a two-hour production.

And you hit pay dirt: Oprah selected it for her book club in 1998.

I first sent it to an editor who rejected it. She said it was terrible and would never work and no one would publish it. So a friend helped me find an agent. She called the next day and said, “This is wonderful; I will sell it by the end of the week.” And she did. So I always tell young people not to take that kind of criticism to heart; it could be wrong.

What was it like to go back to the journals you kept and visit yourself as a younger woman?

It was a very emotional experience, to see how unprepared I was. I was a very protected child and a very protected wife, and when I got divorced, I couldn’t do anything for myself. I was terrified. I’d give myself assignments. For example, I would park my car downtown and walk around just to prove I could do it, despite being afraid. It took practice. But it’s also a life-long lesson: you always have to practice being free and being brave.

The subtitle of your book is “Lies, Lessons, and Love Affairs.” What are the “lies?”

Lies are all the things you say to other people that aren’t true, that don’t reflect who you really are. It’s your public face. It’s not that I lied to people in the sense of telling them things that weren’t true. It’s more that I’d withhold information and let people believe I was someone I wasn’t, or thought something I didn’t. Years ago, I found a copy of Adrienne Rich’s book Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying at Charis Books. It lays out all the ways women lie, like avoiding the question or changing the subject or saying what people want to hear. It pushed me to stop doing those things. Only good things happened when I stopped.

You’ve always been an activist, starting with your work in the civil rights movement and then later with feminism. How are they related?

Yes. In the 1970s, I was very conscious of race, given who my parents were and how I was raised.

I started thinking about gender when I got married. It was very life-altering. I started to recognize the patterns and learned what feminism was and how to use it to live my life. For example, there were things about working for Mayor Jackson (Atlanta’s first African American mayor) that weren’t good for me. If I had been thinking only about race, I would have worked for him longer. An awareness of gender issues made it easier to accept that I had to leave, which was difficult but necessary.

How did you square feminism with your affairs with married men?

If you are a serious feminist, you come up against your own hypocrisy if you do things like have affairs with married men. It’s not honorable, and feminism helped me realize that was something I no longer wanted to do. Of everything I’ve done in my life, the affairs are what I have the most regrets about and would change, because it’s such a lie and so dishonorable.

You are also very upfront about drinking and smoking pot. You don’t edit your life or add introductions to your chapters to put them in perspective. Why take that approach?

Of course, I was very conscious of not betraying trust and exposing people’s lives. But you can’t go back and pretend that you knew then what you know now. It does a disservice to young women looking for life advice if we pretend we didn’t do those things. It puts their goals out of reach. I decided to do this book because I am 40 years older than the young women I meet now, and my life is going well. But I was messy, too, when I was 23. We sometimes sanitize things to the degree that it’s not helpful. We can’t pretend our lives did not include the full range from the respectable to what we’d like to hide. You don’t achieve because you pretend to be someone you’re not. I want people to think “She did a lot”–but I would never have accomplished what I did if I’d lived the life others thought I should live. You have to be authentic about who you are.

Your daughter suggested you burn your journals when you were thinking about what to do with them. Has she read the book?

(Laughs) No, but she’s fine with it. I offered to let her read the manuscript and she said no, she’d already ordered it, which she’s never done with my other books.

Looking for the truth is a theme of your journals. Any final thoughts on what it means to you now compared to then?

The truth–that’s the whole thing; that’s what life is. I’ve learned to tell the truth, most of all to myself. The exciting thing about life is that you learn more as you go along. But it also gets less complicated as you get older. You no longer need to decide whether to tell the truth. You just peel back the layers. You have to figure out who you are. It robs your life of so much richness not to claim it all. I think I’m engaged in living a really interesting life now. I remember as an 11-year-old kid wanting an interesting life, and living this way, with truth, is how I’ve been able to have it.

–Jeanette Zwart, freelance writer and reviewer

(Source)