On October 23, 1837, the 70-year-old John Quincy Adams, now serving in Congress, saw a shocking ad in the National Intelligencer, a Washington daily. A slave woman, Dorcas Allen, and her two surviving children, aged approximately seven and nine, were to be sold that day. Dorcas had murdered her two younger children in a fit of insanity, and the slave-trader who had bought her earlier that year had now returned her as unfit. In his journal, Adams wrote, “It is a case of conscience with me whether my duty requires or forbids me to pursue the inquiry of the case to ascertain all the facts and to expose them in all their turpitude to the world.”

Though he did not favor immediate abolition, Adams had become the most passionate and prominent opponent of slavery in Congress. He had earned the enmity of both Southern members and the Northern Democrats associated with President Martin Van Buren. He had received death threats. He believed that he had lost the support of his own constituents. Fearless as he was, Adams still reminded himself that he could serve no useful purpose as a lone extremist. Yet Dorcas’ terrible deed struck him less as an act of madness than as a judgment on the unspeakable practice of slavery. Was it not his duty to pursue the issue, come what may?

Adams might have chosen prudence, but five days later he saw another ad for Dorcas’ sale. This time Adams, the ex-President, went directly to the slave auction house, a place where Northern gentlemen were not usually to be seen. He met the children and Dorcas, “weeping and wailing most piteously.” The auctioneer, a Mr. Dyer, explained that several days earlier he had sold Dorcas to her own husband, a free black named Nathaniel Allen, for $475. Allen worked as a waiter at Gadsby’s, a prominent hotel and tavern in Alexandria where many Congressmen stayed during the term. Now Nathaniel was trying to scrape up the funds. Dyer doubted he could, so he had placed another ad.

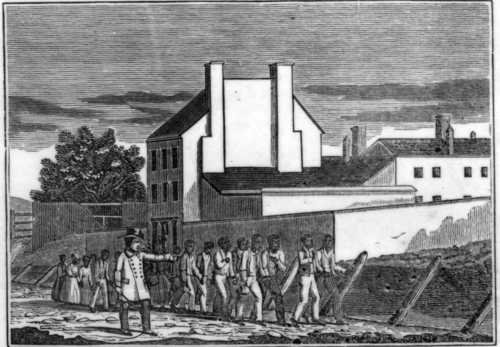

Alexandria Slave Prison

Dyer told Adams that on her deathbed the woman who had owned Dorcas many years earlier had made her husband, Mr. Davis, promise to free her. Dorcas had married Nathaniel and the two had lived as free blacks for a dozen or so years. In the meanwhile, Davis had died, his second wife had re-married and that woman’s husband had sold Dorcas to a slave trader as if he owned her. That very day, Dorcas and her children had been seized and thrown in the Alexandria slave prison, a dismal warren of cells now famous from the movie “Twelve Years A Slave.” Dorcas must have been as staggered as that movie’s Solomon Northrup. That night, she had murdered a four-year-old boy and an infant girl; the screams of the older children prevented her from killing them too. A jury had acquitted her by reason of insanity, though it heard no prior evidence of mental instability. When asked why she had killed her children, Dorcas had said that “that they were in Heaven, that if they had lived she did not know what would become of them.”

Dorcas was no longer a cause to be publicized but a woman to be rescued. Adams returned to the slave house and told Dyer that he had no right to sell a free woman into slavery. Dyer, of course, disagreed. By now Nathaniel Allen had learned that Adams had taken an interest in his case, and came to him for help. He worried that Davis’ creditors would claim Dorcas even if he bought her. Adams promised to track down the Washington district attorney, Francis Scott Key, better known today as the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” A slave owner and aggressive defender of slavery, Key was not sympathetic, but did tell Adams that Allen’s title to his wife could not be contested.

On November 13, Nathaniel came to Adam’ home with Dorcas, temporarily released from bondage. Nathaniel explained that another supporter, General Walter Smith of Georgetown, had examined Davis ‘will and found that he had in fact bequeathed Dorcas to his second wife despite the vow he had made to his first. Nathaniel would have to put the money together. Gen. Smith said that he could raise up to $330. At the time, Adams was so deeply in debt that in April his son Charles had had to send him a check so that he could travel from Washington to his home in Quincy. Nevertheless, Adams promised to add $50—a figure equal to $27,000 today in terms of relative income. Nathaniel and Dorcas exited from Adams’ home and from his life, presumably to freedom.

Adams was not a warm man; he was stern by principle. But principle also made him selfless, generous and brave.

lightning365 liked this

dimsumstudy liked this

jqaspeaks posted this