Problem-Themed Courses

Problems, Harry Potter, Paw-Paws, and Food Trucks.

“I mean that they should not play life, or study it merely, while the community supports them at this expensive game, but earnestly live it from beginning to end. How could youths better learn to live than by at once trying the experiment of living?”

- Henry David Thoreau, Walden

In every academic planning conversation at the Saxifrage School we have tried to keep this concept at the forefront: if a school is to be worthwhile, it must not engage its students in the work of pretending. In an effort to not “play house”, pretending, and only engaging with theory while in school we plan to consistently engage our students with real and pressing problems; problems that are readily experienced and addressed within their own neighborhoods.

This problem-posing pedagogy requires, first, that students do the work of identifying a problem and, as Josh McManus recently put it, then fall in love with that problem. A top-down approach, where students are told what the problem is, limits the motivation that comes from identifying it independently. It has to be their problem so that it resonates with their responsibility, passion, and–most importantly–capability.

There are four brilliant things about problems that make them an excellent a theme for a college course:

1. Problems transcend disciplines, forcing us to reconcile theory and practice.

The complexity of problems make them a unifying force for an educative process. If we want to address the problem of, say, kids drinking too much soda pop for school lunches at a specific school, we have to delve into psychology, nutrition, cultural studies, marketing, politics, the ethics of consumer choice, family studies, health, etc. Moreover, if we are truly working on the problem, our work cannot stop with inquiry, but must act and produce some results. A problem-posing pedagogy requires a productive inquiry and allows courses to be themed not around disciplines, but around real problems in the context of our real neighborhoods.

2. Problem-solving is always valuable.

College students are put in the unenviable position of having to spend tens of thousands of dollars for many years while they are simultaneously earning almost nothing. Unfortunately, most students are involved in work that is “just pretending” and is not seen of much worth to the general population. As Thoreau puts it “The consequence is, that while he is reading Adam Smith, Ricardo, and Say, he runs his father in debt irretrievably.” What if, however, in addition to reading deeply and asking questions, students focused their critique on problems and, subsequently, attempted to solve them. Even a failed attempt at problem-solving is a valuable one because, by definition, problems are yet unsolved; each attempt can offer help to the following as we work collectively towards lasting change. Of course, if students are able to solve a problem, even a small one, their solution has value both socially and economically. Even an attempted (but failed) solution makes for impressive resume fodder, but a successful one is an invaluable experience and a potential source of revenue. A problem-posing pedagogy can serve to improve a neighborhood, as well as earn a student valuable experience and some income.

An example:

“Student Web Developer Clinic for Start-up Ventures”

The Problem: Too many early-stage for- and non-profit ventures lack either the skill or funding to produce a high-quality, informational website to get themselves up and running. This barrier to entry occupied too much of many organization’s already sparse resources. How can these early-stage ventures find a way to get quality web-sites made without spending too much and without burdening the professional community with pro bono requests?

The Solution: Web Dev. and Graphic Design students work in collaborative teams to create quality websites for ventures. Students get paid a small, but meaningful stipend by the organizations and get valuable experience building sites for real clients.

3. Problems are always relevant.

One of the most glaring failures of our nation’s colleges has been their inability to relevantly train students for whatever their post-college work might be. Whether it be deprecated techniques and software platforms, out-dated content, or irrelevant agendas, students often complain that their studies have little or nothing to do with the “real world”. Being good at college, unfortunately, rarely translates to being good at life after graduation. One way to ensure that a student’s work is relevant is to focus it on problems. This is the beautiful thing about problems: they have yet to be solved. Problems, therefore, are always relevant. Additionally, problems are always the focus of the most current and interesting research and practice. Engaging with the conversation surrounding problems is a sure way to become connected to a field’s most relevant issues and capable practitioners.

4. Problems are Motivating

The current drop-out rate statistics tell a difficult story of failure, confusion, and despondency. As we continue to spend our lives in schools, more and more students are wondering “Why?” and seriously lacking motivation. The rates, currently, show that only about 50% of college students graduate within 6 years. Only 50% of all students are graduating and it’s taking them 50% longer to do it! This, of course, is a complex problem, but it is rightly argued that one major contributor is a lack of student motivation and a lost sense of purpose. Why school? The answer, of course, lies in problems; it lies in a School’s ability to equip us with the skills, wisdom, resources, confidence, and relationships weneed to see and solve problems.

The classic example is that of the High School Calculus class when the student asks “Why does this matter? Will I ever use Calculus after High School?” It’s a trite, but important question. The key part of the question though, is the word “after”. Since we are spending so much of our lives in schools, students are becoming restless and the question, instead, should be “Will I use this now?"

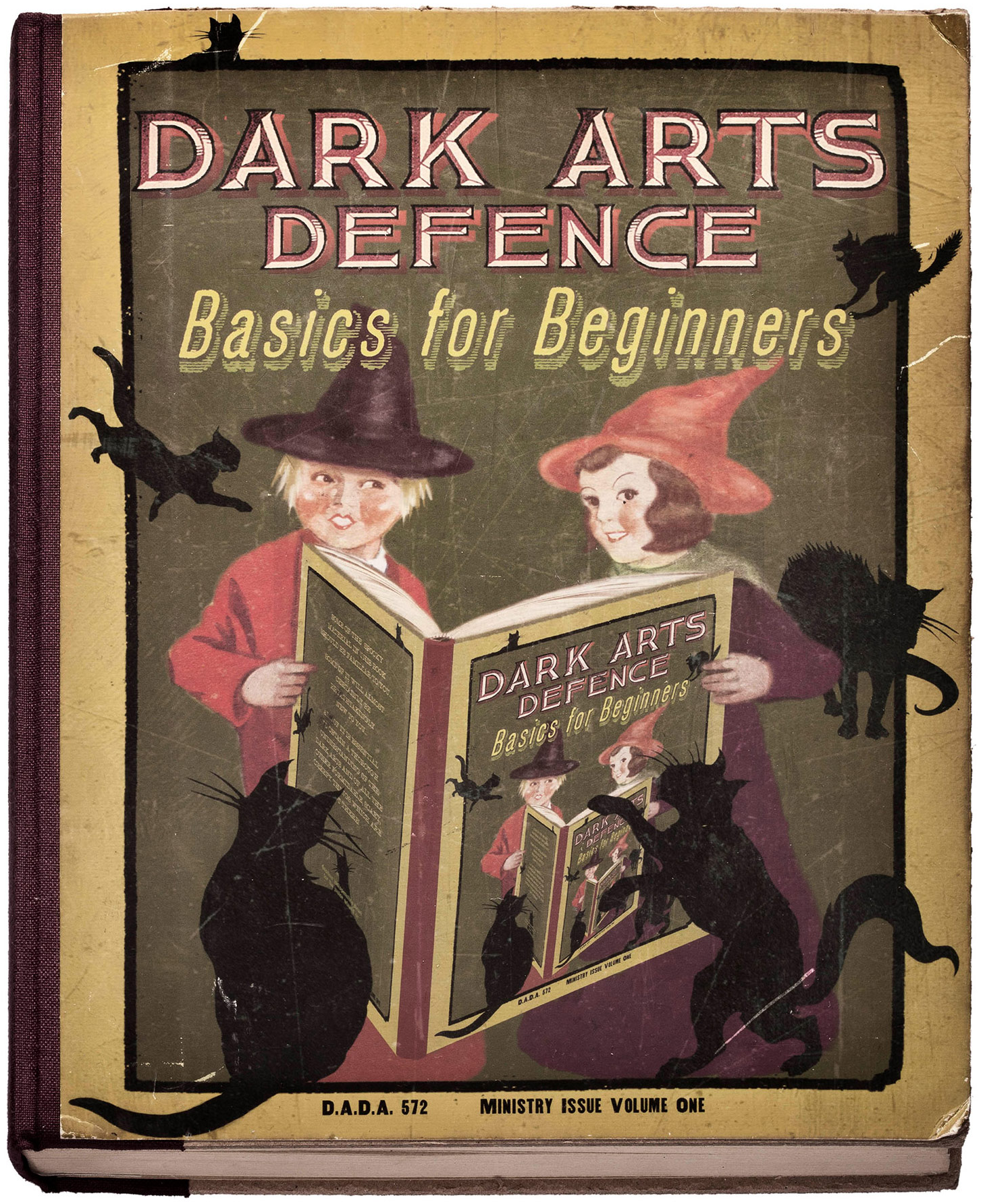

A better, more interesting example, comes from the beloved Harry Potter series. In Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, the–arguably–most important class at Hogwart’s School for Withcraft and Wizardry is upended by everyone’s least favorite teacher, Dolores Umbridge. The Defense Against the Dark Arts class, under Umbridge’s instruction, has her students reading "Dark Arts Defence: Basics for Beginners” so that they understand only its theories in preparation for their examinations. This conflict, I would argue, is one of the major reasons for the popularity of the Harry Potter series. J.K. Rowling’s story is one where school is meaningful and amazing. The ennui experienced by so many students is brilliantly contrasted by the epic bildungsromanic* education of Harry Potter and his friends. Sure, they have magic and wands, but the important nature of their education is that they are learning how to do things that save the world and the lives of their friends. Moreover, the things they are learning are not for some distant future life “after school”. They are going to be faced with great conflicts that night. As the TV show “Heroes” so tritely/aptly iterates again and again “Save the cheerleader: Save the world.”

*It is fun to note that this word can be used literally here, the german “bildungsroman” translates to “education novel”. In this sense, the Harry Potter series is, perhaps, the quintessential bildungsroman.

In response to Umbridge’s de-problematizing of their coursework, Harry and Friends start a secret classroom behind the walls of Hogwarts. They recognize there are real and serious problems on the horizon (Voldemort, Dementors, etc.) and need to keep learning. This sense of responsibility is one that is difficult to teach but of foremost importance. Responsibility, however, cannot be instilled unless students are engaged with real work addressing real problems. There is no responsibility to be found in pretend situations. This is what Harry is talking about when he warns his fellow students about joining his rogue educational group: “Facing this stuff in real life is not like school. In school, if you make a mistake you can just try again tomorrow, but out there, when you’re a second away from being murdered or watching a friend die right before your eyes… you don’t know what that’s like.” Hermione recognizes “You’re right, Harry, we don’t. That’s why we need your help.”

This education novel (the most popular book series ever with ~450 million copies sold) is the story of our well-schooled generation, in part, because in Harry Potter’s school he is not merely studying, he is living earnestly. He is learning by facing real and immediate problems.

———

Here’s a postscript with one last example (okay, maybe two). First: Food Trucks.

Currently, the Saxifrage School is engaged in a brief partnership with the newly formed Pittsburgh Mobile Food Coalition: www.pghmobilefood.com. Even though our course offerings are still quite small, we wanted to begin involving ourselves in the sort of pedagogical exercises that we hope will be a significant part of our future. The Pittsburgh food truck issue is just the sort of focused problem that we could imagine our students undertaking in future courses. It is concerned with politics, law, economics, cultural studies, marketing, business, nutrition, food studies, etc. and is happening right now in our neighborhoods.

So, we are working with the Food Trucks to practice education, promote awareness, lobby city council, and market product in the hopes that the City will improve legislation to encourage the growth of the local food truck industry. As mentioned, real problems are necessarily complex. We were able to provide web development assistance (from our Web Development students) and work to function as their educational partner to put on a couple classes themed around the Food Truck problems. Its not quite a Voldemort-sized problem, but its a great start.

Second: Paw-Paws.

Local hero Andy Moore is attempting to address another problem: the near-extinction of a fruit tree native to our region, the delicious and tropical paw-paw tree. In his work, Andy is writing a book on the Paw-Paw chronicling its history, decline, and recent (albeit still tiny) resurgence. As he records the paw-paw story, he is also acting as an advocate and educator for the growth paw-paw trees and an industry that might re-introduce them to the larger population. Once again, the paw-paw problem is a problem Andy first posed, then fell in love with, and is now seeking to address in all of its exciting complexity. Its valuable ($4,714 pledged on Kickstarter), motivational (everyone gets excited about it, especially when they taste one), relevant (even our most foodie or farmer friends have not tried one before and we could use more local fruit diversity), and very complex (the problem is horticultural, economic, and mysterious).

For more information, the record of his successful kickstarter campaign can be found here: http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1492998860/pawpaw-the-story-of-americas-forgotten-fruit?ref=card