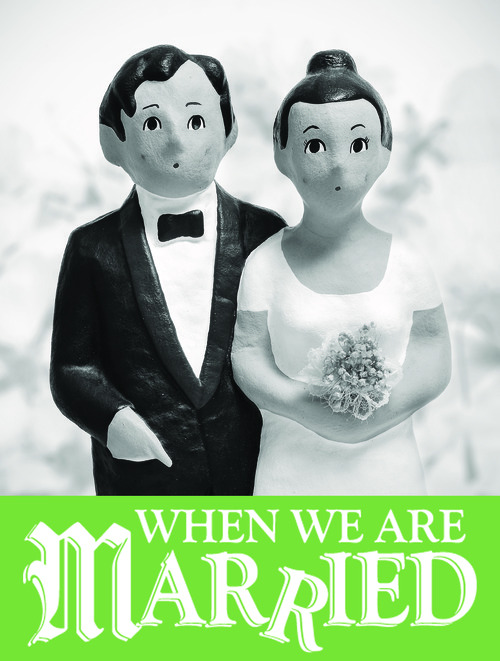

When We Are Married: To Be or Not To Be Married?

By Dan Sullivan

All hail the Emerging Playwright, as celebrated by the Denver Center Theatre Company’s Colorado New Play Summit; but don’t write off the Vanishing Playwright.

All hail the Emerging Playwright, as celebrated by the Denver Center Theatre Company’s Colorado New Play Summit; but don’t write off the Vanishing Playwright.

Today’s example: J.B. Priestley and When We Are Married.

Such a sweet title. For years I thought that Priestley’s 1938 comedy concerned a moony young couple looking forward to a blissful 50 years together, like the kids in the Beach Boys’ “Wouldn’t It Be Nice?” How did that work out?

And what ever happened to Priestley? Once a literary titan, he’s almost forgotten today: an old master whose name still rings a faint bell but whose 60 books tend to be in storage when you hunt for them at the library.

Plays, novels, short stories, biographies, literary criticism, political tracts, journalism, radio talks, TV documentaries—Priestley did them all and did them well. Too well, probably. Critics distrusted his facility.

He also stayed around too long—more than 50 years. When the angry young hero of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger (1956) throws down his Sunday Times in disgust, it’s because he refuses to read one more J.B. Priestley disquisition on anything. (As Jack Benny used to say, “eventually they resent you.”)

Beyond that, Priestley’s private life was scandalously ordinary. No sexual romps, no drug rehabs, no sickening failures, no miraculous comebacks. No tell-all biography drama there. Even his name was flat. “J.B. Priestley” (for John Boynton) sounds like a bank president, an attorney, an assistant principal— honest, reliable, humdrum.

Wrong.

Try staunch, forthright, pugnacious. Hear him in the 60s: “One of our poets told a friend of mine in New York that I had a second-rate mind. I have a second-rate mind. But it is my own; nobody has hired it, and what it chiefly desires, even more than applause, is that English people have a good life.”

He kept on writing until his death at 89 in 1984, a latter-day Shaw, full of energy and opinions. A central one was that “ordinary” people knew more than the experts hired to sell them something. He loathed the Cold War, the “central vacuum” of modern politics, the greasy hustle of public relations.

What Priestley cherished was private relations, as remembered from his Yorkshire boyhood before World War I. When We Are Married looks back on that world—and not in anger.

The title—originally Wedding Group—throws you off. No moony young lovers here. Rather, three 40-plus couples who’ve been married forever. Tonight is their silver wedding anniversary (it was a joint ceremony), so let’s have a toast.

The toastmaster is a bit fuzzy on the history of marriage (“It goes back… right back to… well, it goes back”), but he’s dead certain about its utility as an institution, because what would you women do without marriage? What would us men do?

This brings a hearty laugh, not that anyone’s trying to be risqué (the year is 1912), but these folks have known each other for years, it’s a small town and the bubbly is flowing.

Jollity reigns until our six friends discover, thanks to I won’t say what, that they aren’t the respectable married folks they thought they were. They’re not married at all. Some problem years ago with the marriage license.

This isn’t funny—except to watch. The outcome can’t be revealed, but we are dealing with Priestley the entertainer here, not Priestley the scold, and he brings his tale to a smooth, safe landing. But not before certain characters have learned either to speak up for themselves or to leave off nagging. Priestley’s message (after three marriages of his own): Count your blessings.

This isn’t Strindberg, but it’s as practical a view of marriage as that provided by our better sitcoms (The Middle and Modern Family, especially) and it leaves a more pleasant aftertaste than other fables I could mention, such as We’re Not Married, a mid-50s take on Priestley’s theme (though not credited to him) from 20th Century Fox.

This was an omnibus comedy starring the newly-minted Marilyn Monroe and a clutch of old reliables such as Fred Allen, Ginger Rogers and Eve Arden. Again, a handful of married couples find themselves liberated from their vows by a legal glitch, with various outcomes, which, by the 1950s, included divorce. Though nominally sophisticated, the story provides a rather grim survey of postwar togetherness, sometimes as a mask for actual dislike. Can these marriages be saved? For what?

Where We’re Not Married presents marriage as a somewhat lonely business, When We Are Married sets it in the heart of a community. This gives it a topicality it’s never had before. You can’t see it in an election year without being reminded of our gay marriage debate.

What is marriage? What’s it for? Who’s it for? Just the questions facing our toastmaster. Suddenly, a harmless little “farcical comedy” becomes a conversation-starter. Priestley couldn’t have foreseen this, but he would have approved. Get them talking!

As a dramatist, he also knew the value of an uptight, rule-bound community as a background for a farce-comedy. The first rule in farce is that the characters have to care, and the folks in When We Are Married care desperately about their respectability. Not that they’ll be tarred and feathered if they’re outed—this is Yorkshire, not the Wild West—but people are going to talk and, worse, they’re going to laugh.

All this makes for prime comedy. The husbands haven’t a clue as to how to get out of this mess and the wives are furious about having been dragged into it. As if by a law of nature, the men must now sneak off to their club to lick their wounds, while the women repair to the parlor to elaborate their accusations.

Good strategy Priestley seems to be saying. Stick with your tribe. For all his forward thinking, he had nothing against tribes, clubs, veterans’ posts and sewing circles, and he mourned their loss in the awful “central vacuum.”

That was the real enemy.

“More and more I distrust that bigness before which a man feels helpless and baffled,” he stated. “Once past a sensible size, things get out of hand, acquiring an alien, sinister life of their own.

“If a city is miraculously efficient but is also filled with people who are worrying themselves sick or becoming uglyminded and cruel or turning into dim robots, it is a flop. If the people in a neighboring country are comparatively poor, but contrive to live zestfully, laugh and love, still enjoy poetry and music and talk, then that country has succeeded.”

It’s good to have Priestley out of storage.

Dan Sullivan directs the O’Neill Theater Center’s National Critics Institute and teaches journalism at the University of Minnesota. He has reviewed theatre and music for the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times and the Minneapolis Tribune. This article appeared in Applause magazine.

When We Are Married plays Denver’s Stage Theatre Nov 16-Dec 16, 2012. Tickets: 303.893.4100 or 800.641.1222.