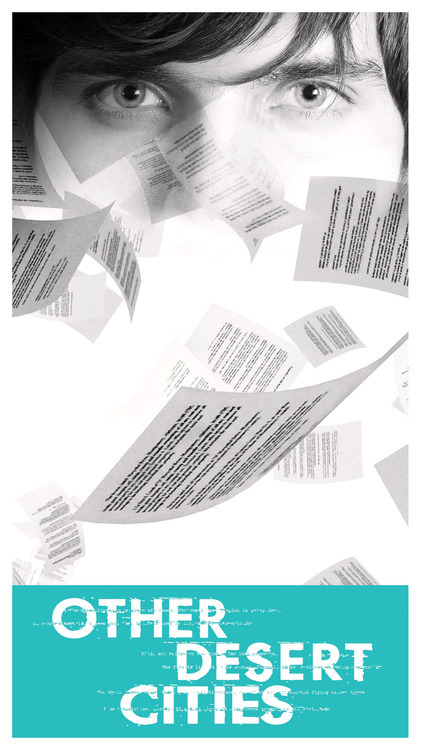

Desert Homecoming

Other Desert Cities playwright Jon Robin Baitz expounds on the

Left Coast, the political Right and an artist’s necessary exile

By Rob Weinert-Kendt

The playwright Jon Robin Baitz walks healthily among the living, but in some ways his articulate, carefully constructed plays feel like throwbacks to a more literate, less cynical age. Plays such as The Substance of Fire, Three Hotels and The Paris Letter, map out internecine battles of love and loyalty among family, friends and lovers with a comic clarity that evokes Shaw, and a fraught psychological texture, thick with explosive secrets and lies, that recalls Ibsen.

The playwright Jon Robin Baitz walks healthily among the living, but in some ways his articulate, carefully constructed plays feel like throwbacks to a more literate, less cynical age. Plays such as The Substance of Fire, Three Hotels and The Paris Letter, map out internecine battles of love and loyalty among family, friends and lovers with a comic clarity that evokes Shaw, and a fraught psychological texture, thick with explosive secrets and lies, that recalls Ibsen.

Given those antecedents, it’s surprising that his career until last year was bookended by two formative West Coast experiences that would seem to belie his plays’ well-made classicism.

A native of Los Angeles, Baitz got his first playwriting education from the now-defunct Padua Hills Playwrights Festival, where mavericks like John Steppling, and Maria Irene Fornes pushed the form to its extremes. Then, after success as a New York-based playwright, Baitz went back West in 2006 to create the hit ABC-TV drama “Brothers & Sisters,” only to be fired after the show’s first season in a welter of mutual recrimination. It left him reeling and, as he admits now, “half-mad.”

From the ashes of that defeat came a phoenix called Other Desert Cities, another play about smart, funny people with deadly serious problems. It opened to acclaim off-Broadway in early 2011 and transferred to Broadway that fall, constituting Baitz’s long-overdue main stem debut as a proper playwright. (His adaptation of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler came to Broadway in 2001.) Though the play isn’t autobiographical, Baitz says he wrote much of his own fired-from-TV frustration into Brooke Wyeth, a nervy novelist who returns to her parents’ Palm Springs home for the holidays bearing a tell-all memoir that could rattle every last skeleton in their closet.

From the ashes of that defeat came a phoenix called Other Desert Cities, another play about smart, funny people with deadly serious problems. It opened to acclaim off-Broadway in early 2011 and transferred to Broadway that fall, constituting Baitz’s long-overdue main stem debut as a proper playwright. (His adaptation of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler came to Broadway in 2001.) Though the play isn’t autobiographical, Baitz says he wrote much of his own fired-from-TV frustration into Brooke Wyeth, a nervy novelist who returns to her parents’ Palm Springs home for the holidays bearing a tell-all memoir that could rattle every last skeleton in their closet.

Backed up in part by her barely-sober aunt Silda, Brooke challenges the complacency of her formidable parents—an avuncular film actor, Lyman, and a whipsmart former screenwriter, Polly, Hollywood Republicans who were once close with the Reagans.

In a not-coincidental overlay, the family’s political differences are exacerbated by the timing: The play is set in 2004—one month after President George W. Bush was re-elected and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan stretched ahead seemingly indefinitely.

Baitz sat down late last fall in New York to talk about the play’s genesis, his arm’s-length love for his hometown, and other pertinent matters.

Rob Weinert-Kendt: A lot of the play’s energy derives from an East Coast/West Coast divide. Brooke’s parents moved West, remade themselves and raised their kids there. But she rejected that and moved back to New York.

Jon Robin Baitz: It’s interesting because my brother and I have both done the same thing. He’s a composer and I’m a playwright, and we both sort of rejected some idea of being comfortable in LA.

I could not in fact have written the play from LA. I had to be in exile. It’s very much a play about exile. The Wyeths have placed themselves, for various reasons, in this scorching, stultifying desert, where everything is sort of in amber, from 1972 to 1980-something, the Annenberg/Reagan years. I think I’ll probably keep coming back to LA as a subject. Or the West.

RWK:Right, Palm Springs isn’t LA; it’s a whole other state of mind.

JRB: It is. Palm Springs is about the suspension of all but the mirage. It has a kind of eternally beautiful-and-damned quality about it that I find compelling. Tremendous beauty, tremendous exhaustion. Retirement in all senses.

RWK: When you said “mirage,” I thought Las Vegas, but that feels more transient. Folks really plant themselves in Palm Springs.

JRB: Completely. After my dad retired from Carnation, my parents bought a house in Palm Springs, behind gates, with some tennis courts, a little community. They would go back and forth between LA, their little condo off Burton Way, and their little house in Palm Springs. I understand the desire to separate yourself from the forces of nature because the forces of nature in modern urban living are pretty ugly. It’s precisely the refusal to admit those forces that makes the place so compelling.

RWK: The play was written during the Bush era, but do you think its politics still resonate in the age of Obama and will continue to be relevant?

JRB: I think they will, given the identity confusion within conservative American politics, which is so much a part of the play and of my own area of interest—how a party shifts on its axis and becomes something else, while there are these marriages going on between unlikely bedfellows who seem to marry their ideas together in a kind of odd nexus of government interfering in certain parts of your life and not in others.

RWK: But the brand of moderate Republican represented by Polly and Lyman seems absent from the national political stage.

JRB: Well, because they have been silenced and kicked out and replaced by Tea Party politicians—and usually, with all possible respect, somewhat illiterate Tea Party politicians who have no sense of macro- or micro-economics, no sense of American history or who misread it endlessly. So the people in this play are virtually extinct, and they’re in the desert near those dinosaurs at Cabazon.

RWK: Polly and Silda are very entertaining, acidly witty characters. Did they ever threaten to run away with the play?

JRB: Yes. There are places where Silda occasionally hijacked the play; I’d write pages and pages and you’d just see the play vanishing in the distance, and Silda doing “The Silda Hour.” That’s why one does drafts. I certainly heard them very clearly, Silda and Polly. Restraint is everything, of course, and to let them go unfettered would actually become sort of monotonal.

RWK: Do you calibrate funny vs. not funny as you write?

JRB: It’s all in the service of the narrative. A joke is only useful if it does a lot of other work.

RWK: Brooke is there to dump cold water on everything. She has a lot of fine qualities, but you’re not easy on her.

JRB: She’s had a lot of trouble. She’s capable of being funny, but she’s got a lot of scar tissue. My characters tell me what they are. And a lot of the way Brooke feels is the way I’ve felt at various times in my life when I’ve been in extremis. She’s a portrait of the artist in despair. And when you’re decompensating, humor is very hard to find, unfortunately.

RWK: Your despair came after your “Brothers & Sisters” breakup?

JRB: Totally. The Brooke despair was my trying to make sense of having left LA the way I did, in personal misery, professional misery—with this kind of hysterical, half-crazy, incredibly self-destructive faux-truth-telling. Telling the truth is perhaps my expensive hobby, you know? For some people it’s horses.

RWK: Brooke may represent the artist speaking her truth, but you let the other characters speak a lot of opposing truths back to her.

JRB: Listen, I think there’s a danger in being outraged and having self-righteousness to the extent that she does. The certitude is troubling, the sense of entitlement on some level is really very dangerous—the lack of humility, the notion that you can appropriate without consequences, that your moral center is so much more beautiful than everyone else’s. And people lie to themselves, even a recovering depressive who’s just finding her way back. I think sometimes the fear of depression is much worse than the depression, and Brooke is in that state; she’s running as fast as she can away from another episode, and she’ll do anything she can.

Brooke has the same disease that her mother has—this sort of absolutism. In her mother’s case, it’s sort of wonderful, because she’ll sort of fight to the death for this family, this cause of hers.

RWK: Until that fight doesn’t have any love in it anymore.

JRB: Well, love is not necessarily a soft and pleasant thing. I’ve been loved very hard by people. I’m very conservative when it comes to things like decency, just basic decency. And I guess the play is so simple, on some fundamental level: It argues for humility in the face of what you don’t know and compassion in the face of what you do know.

Other Desert Cities plays Denver’s Space Theatre March 29-April 28, 2013. Tickets: 303.893.4100 or 800.641.1222

Rob Weinert-Kendt is associate editor at American Theatre, and has written about theatre and the arts for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Variety, The Guardian and The San Francisco Chronicle. A slightly different version of this piece ran in the December 2012 issue of Performances magazine.

2 notes

waitwhatomg liked this

frrreshoutthebox-blog reblogged this from denvercenterblog

denvercenterblog posted this