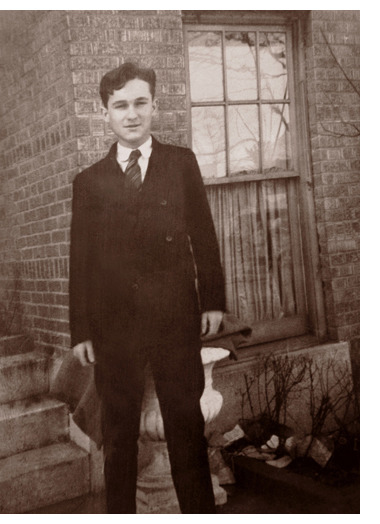

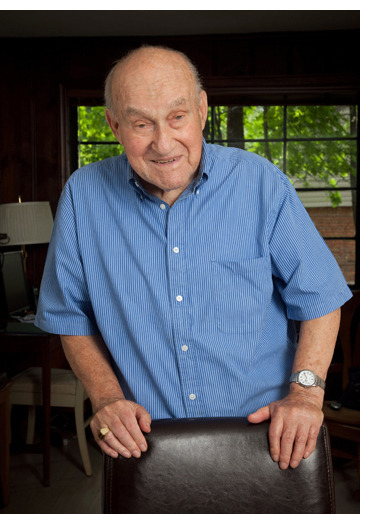

MURRAY FORER WAS BORN IN TRENTON NEW JERSEY BUT GREW UP IN THE BRONX. HE WORKED AS A TEENAGER FOR $2.00 A WEEKEND FOR WESTERN UNION DURING THE DEPRESSION. HE MET HIS WIFE DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR WHILE HE WAS IN THE SERVICE IN VIRGINIA. HE HAS NEVER HAD A CIGARETTE OR TASTED ALCOHOL. HE’S A DIEHARD BASEBALL FAN.

My name is Murray Forer, and I was born 4/22/14, Trenton, New Jersey. My parents were born in Russia and how they got down to Trenton I don’t know. The less you ask me about them in the beginning of my life, the less I’ll tell you, because I don’t know. I was only nine years old when we moved to New York. And we moved into the Bronx. We lived at 2095 The Grand Concourse and I guess we moved there – I lived there about a year or two. Then we moved to University Avenue, 1847 University Avenue, near Tremont Avenue. And we lived there until I got drafted in 1942. I lived with my parents and three sisters.

It was very up-grade. The Concourse was a beautiful street. And University Avenue, to give you a concept of what it was, across the street – I lived 1847 University Avenue. There was no such thing as buying, we rented. When we first moved there from the Concourse, we had five rooms of a brand-new – we moved in when the men were still working. It was $110 dollars a month. But as the girls left the nest I was the baby.–we moved in the same building. One was 1847. The other side of the courtyard was 1841. That I know. We moved to a three room apartment and the rent was $50 a month

Congressman LaGuardia lived directly across the street. Then, you know, he became Mayor. But he was a congressman at that time. We used to see him sitting out – he had a lawn, one of the few lawns on University Avenue that wasn’t an apartment. He’d sit there like this, many, many times.

There was one movie theater, Park Plaza Movie Theater. But because of finances, we didn’t go to the movies too much. First of all, it was 35 cents. And once in a while – for entertainment, there was the Paradise Theater near Fordham Road on the Grand Concourse. And we used to go there, because they had live vaudeville acts. We used to see – I just have to think – we saw Eddie Cantor and George Jessel, which was a major, major event. And they played there for eight, ten weeks. But, you know, it was 35 cents, not too shabby. But across the street was a Crumbs Ice Cream Parlor, ten cents, so, you know, you’re talking about 50 cents.

There were plenty of open lots in those days but. Nobody had any money to build.

But it began to surge shortly after I graduated from high school, graduated from Evander. I noticed a lot of cranes, and especially on the Concourse. That became prime real estate, prime.

Going back now, I went to PS 82 on the corner of Tremont and University Avenue. Oh, wait a minute. I didn’t go to 82 if I went to school when we lived on the Concourse we went to PS 26 for about a year then PS 82. It was a new school. My class was the first class that graduated PS 82. I remained friendly with a few fellows there, but they’ve passed away.

As a matter of fact, digressing, most every friend of mine in school, elementary school, high school, college, and law school, have passed away.

So after 82 I went to Evander Childs High School. That was 183rd Street and Creston Avenue.

In Trenton my father was in the furniture business. But he outlived the possibilities in Trenton. And he had visions, and he came to New York. But New York was too smart for him, unfortunately. So he was in a fringe of Wall Street, financing small businesses. You know, and that didn’t last long. during the Depression. So when I say Wall Street was smarter than him, the whole economy was – not only him, but everybody else.

So he soon gave that up. And he had a chronic cough. So he had to go to a different climate, which was Denver. Well, Denver, they had a lot of tuberculosis – a lot of people that had those problems. My mother stayed behind. She didn’t want to disrupt the family. My three sisters and myself were all going to school. If I remember, they were all going to Evander Childs before me. And I remember them discussing it. “No, no, no. We’ll stay right here,” which was smart because we knew nobody in Denver. And my sisters were growing up, and all their friends were in New York, and they all married New Yorkers. So it was a wise decision, in retrospect. So I stayed behind with my mother and graduated from Evander Childs high school in ’31. My father died, I would say four, five years after he moved to Denver.

After I graduated from Evander Childs, I was 17 years old. It was ’31. I had a summer job at Western Union. There were in the Flatiron Building on 23rd Street.. I got paid 9/10 of a cent for every telegram I delivered. So if I delivered more than 200 in a day I got $2.00. I did that every Friday afternoon, Saturday and Sunday when I was at Evander.

After High School I went right to college, New York University. That was on the Heights and Washington Square at that time., and. They eventually sold that uptown. And now they own half of Washington Square. But I went to the downtown school. I went there every day by subway, the Woodlawn- Jerome from 176th Street Station to 8th Street Station, Astor Place Station. It was only a five-minute walk to the College. The fare was five cents

After college I went on to Law School. I graduated law school in ’37- – And what complicated it, I went to school in mid-year, in January. And if I wanted to take another year, I’d get a B.A. degree. But in those days, money was far more important than degrees, so I went right through from undergraduate to law school. I started law school in January, mid-year. Law school was three years. The law school was excellent, although it doesn’t compare to what it is today. But I was quite – not active, but I was very interested in the law school. I used to attend all the post-graduate lectures, social affairs. It was very nice. I knew John Sexton, who’s now the president of NYU. But he was dean of the law school.

I had a very nice college career. The one thing that everybody was focusing on was staying alive financially. So many people, the day end, would have a night job, work in a library for 20 cents an hour, and the same with me. I used to work on Friday afternoon, Saturday, and Sunday at Alexander’s. on Fordham Road in the Bronx.

But that 20 cents an hour, we had to punch in. And when I’d got classes on Friday, my last class was 12:00. And if I had to scoot up to Fordham Road and get in at 12:45, I’d make that 15 cents on the clock. No sprinter ran faster than I did. And it may sound silly to you.

Yeah. I had a little pull there. My youngest sister worked for them. And she became one of the first buyers, other than management, that went out on her own .She was quite a character, quite a good – and the family, the Farkas family, the owners, they liked her very much. And she was friendly with them for many, many years after she left. As a matter of fact, she met her husband through that organization. And after that, she asked – I needed a job; I needed to have money. : But every nickel, every nickel – my mother would walk 10 blocks. I remember there was an ad for a grocery store about 10, 15 blocks for matzos. It was a penny or two pennies cheaper, and she asked me to go with her to carry it back. She could nurse a nickel as far as you could stretch it. And everything, I must tell you now, must sound funny to you, where money is like water. But in those days, it was not.

Between ’37 and ’42 when I was drafted, I was starving

During the summers, I used to work up at the Catskills. while I was at NYU. I worked up at the Napanoch Country Club, Napanoch, New York. It’s right near Ellenville.

And I started as a busboy, and I always strived to rise. I went up busboy to waiter, and I was one of the few, few captains of a dining room. They were all German – that’s their profession. I used to walk around in a tuxedo, and I made a bundle of money., $500 a summer.

I remember Max Schmeling used to train at Grossinger’s. And they were smarter than the Napanoch manager. He was a Nazi from the word go.

And they refused to let him come back training for the Joe Lewis fight because he was German.

Napanoch grabbed at it because it was big business. But it turned out to be a disaster, because Napanoch, like all these other places up in the Catskills, were Jewish-oriented. And that didn’t set well with them. They made it up, half of it anyway, or something, because the reporters had to pay. And also not guests of the hotel, but guests to come up for one day to see the training

They have any big-name entertainment at Napanack they had the Ritz Brothers. They had Lillian Roth. I forget. [LAUGHS] But Lillian Roth was there all the time. The Ritz Brothers were there all the time. You know who they were.

The owners did very well. But then that business dried up, like it dried up everywhere, everywhere. There were hundreds of these – even Grossinger’s went busted. And the only one that I think is still alive is the Nevele in Ellenville.

The Catskills used to be the Mecca.

The last thing, ’37, whatever you read now about the recession, they talk about the Great Depression. That’s what they’re talking about, in ’35, ’36, ’37. They’re talking about eight, nine percent unemployment. It was 25 percent then. And you couldn’t get a job if you stood on your head. Oh, I took the bar exam right after ’37, when I graduated. And I passed it the first time. Those days, it was 60 to 70 percent passed, 30 to 40 flunked. But it didn’t mean anything, because the last thing this country needed was a young, Jewish lawyer without any family connection. If my father owned a Chase Manhattan Bank, I’d have been doing alright, worked in a big Wall Street firm.

But I worked at two law firms, two law firms, and the first job I made five dollars a week, which was a normal law clerk’s job. I was still living at home so I could manage on five, 10, or 15 dollars. But yet when they paid me five dollars, and when that bookkeeper took that one percent social security, I could’ve killed her, because I needed that five dollars.

The first job was Wise, Greenwald – and what’s the last name? Wise, Greenwald, and Moscowitz – no, Wise, Greenwald, and Moss. At 80 Broad Street.

But I was making no headway, and I had a lot of ambition. There were 15, 20 lawyers; it was a pretty big law firm. And whenever I made a little headway, some client had a son who’d come in, and the senior partners called me in. They’d say, “Murray, you know, I’ve got to take care” – Ted Cohn, I remember him. He was a Harvard Law graduate, but his family was a big client of the firm. So whatever headway I made –

And then the second job was Ellis, Ellis Associates, in Rockefeller Center and there I finally made 20 dollars a week But that didn’t disturb me. When some of the fellows were there ten years and making 35 dollars, I made up my mind that is not for me. No, even though I gave seven years of school, I said, “That’s not my style.” And there was another fellow in the same – worked right with me, and he was a Harvard Law graduate. And we used to talk all the time. His name was Bruce Rabison. And that name has significance, because he was a Yeshiva graduate. And he was not ordained, but he was –very observant.

Yeah. But we used to talk time and time again. “Hey, Bruce, want to get out of here?” So luck would have it, the war heated up, preparation for the war heated up. And they started drafting already. So his uncle owned a very big men’s shorts and undershirts company in– Allentown, Pennsylvania.

So he said to Bruce, he said, “Bruce, I got an idea for you. You want to get out of the law?” He says, “Yeah” – both of us. “We’ll give you some shirts and tops. You can sell them at the drop of a bucket.” Everybody was wanting them. So what we did, one day we quit. He gave up seven years and I gave up seven years to carry a bag – with shirts. And we took off like a rocket. So he told us, “Why the hell are you going to give them the most desirable thing? Go out and buy some sweaters, some shorts, and socks, and things.” And we did.

This was in the early ’40s, I think, yeah. So we took a little office on 1261 Broadway, and we bought – and we did very well. Unfortunately, I only had about eight, nine months before I got drafted. But I would trust him with my life. I said, “Bruce, I’ll go in, and you stay. Hang on until they draft you.” So he stayed in about eight months, and sure enough – They got him, and he became a linguist for the army, learned Japanese.

He was smart as a whip. And when he had liquidated inventory under the gun –

we came out even. It wasn’t a big business. But it was just putting our feet wet. And it took a lot of courage for him and for me to give up seven years of school.

In the Army, I was sent – my basic training was at Camp Lee, in Petersburg, Virginia.

I was 27 when I was drafted–

PK: So that was not young for the Army. They were drafting guys much younger, right?

MURRAY FORER: And older. They were drafting up to 38.I went to Camp Lee for basic for eight weeks, and then they sent me to – a new port of embarkation was being established in Norfolk, Virginia. And that’s about 40 miles from Petersburg, and made us walk, the whole camp. I was in pretty good shape in those days better than anybody in the world.: I used to play baseball quite a bit. I just meant on the street. Stickball.: But I was in good shape anyway.

Anyway, when we got to Norfolk, I was assigned to a job that allocated freight. They’d bring in billions and billions of dollars’ worth of freight, but then they’d allocate to ships going to different areas, all very secretive. And I liked that work, because a lot of guys in the Army had pencil-pusher jobs, which didn’t mean anything. All they were there is because they were there under force, and a lot of the guys, they couldn’t manage a hot dog stand. But I took my work very seriously. The war depended on me. And I felt that way. And time and elements didn’t mean anything to me.

I used to have calluses – only allocating freight. tanks and other things, I didn’t do the loading . But I effectuated the allocation to make sure they got on. So I had a pretty good job.

I had the same job for about a year, a year and a half. My commanding officer – let me digress for a minute. It was a military establishment of course, but it was only in reality a multi-billion-dollar staging area of freight. We didn’t handle personnel. That was handled about five miles away. We used to see the troops go by the thousands. But, as I told you, they drafted many, many multi-millionaires, CEOs of various corporations – General Electric, General Motors, everything. All these big corporations, they deliberately gave them their traffic department; they gave them this department. And one of the men was Major Schey. His desk was right next to mine. And he was a big textile executive from New York. He owned ladies’ hosiery, men’s hosiery. And he wasn’t drafted, but he volunteered, like these other executives. All of Madison Square Garden, General Kilpatrick and Ted [DEACON?], they were all there. And his desk was right next to mine.

I told you a minute ago, I took my work very seriously. I did what I was told to do, plus. So I did my daily job, and unbeknown to me, he had an interest in me. One day, he called me in and he says, “I want you go to officer school, as a major. I got a job. It’s not a pencil-pusher job; I find it very stimulating and very attractive and very productive. You have to go to school.” So they sent me to school, to officer school, down in New Orleans. They used to call us the “90-day wonders.”

And while there, they had a very strict policy: never bring a lieutenant, your lieutenant, back where you were an enlisted man, because you’d never get respect. These guys would say, “I knew you when you were in the bunk.” They brought me back. And I never, never had a single bit of trouble. The men that I used to bunk with, they’d already have to salute me, too, but I never, never took advantage of that.

And, you know, there’s an old phrase: “It’s pretty hard to walk with kings and still keep the common touch.” I had that ability. The one thing that I’m proud of, that I could walk with kings and never lose the common touch. So I was there at the same job that I did as an enlisted man as an officer. That was in: ’44. And I did that job until I got discharged, and I got discharged as a captain. So I got discharged as a captain, which wasn’t so bad from a private to captain.

PK: Tell me how you met your wife.

MURRAY FORER: I got married in October of ’45. This you won’t believe. It’s a most interesting marital relationship. [LAUGHS] : The story I tell you now I’ve told one million times, plus.

In ’44, Rosh Hashanah, there was a little temple in Norfolk, Virginia, with about 100 seats, 120 seats, called the base and said any Jewish officer that wants to avail themselves of services on Rosh Hashanah are most welcome to come to our temple. I don’t know how many Jewish officers there were in my outfit, but only eight of us accepted that. So the morning of Rosh Hashanah, [LAUGHS] we get in a big truck, bigger than this building, and drove down to this temple in Norfolk, Virginia.

All eight of us walk in. Our usher says, “We don’t have eight seats in a row. Whatever you see, take it.” So I walked down the aisle, and as I shimmy in to my seat, on the other aisle, some girl walked out. If I saw her for a blink of an eyelash, that’s a long time. I don’t know what happened to my heart, but I said, “Boy, I don’t know who that is.” But anyway, five minutes later, there’s an empty seat in front of me. So I tapped that girl. I’m in shul. [LAUGHS] I’m picking up somebody. [LAUGHTER]

I tapped her on the shoulder and I said, “Miss, there’s a man sitting over there. There’s a girl sitting next to him. Do you know who that is? By any chance, do you know who that is?” “Yeah, that man’s my father and that girl’s my sister.” I almost died. I said, “Yeah? What’s her name?” “Sylvia Kruger.” “Does she live in Norfolk?” “Yeah, lives on Redgate Avenue.” What’s that, eight words? Ten words? That’s it. Her family was from Norfolk: The father owned a haberdashery. And the mother was a housewife. There were three girls and one boy. The boy was in the Army, too. He was a doctor.

Every eight days, we used to have a day off. Other ships come, or other ships –so we had nothing to do that one day. That was on a Sunday, a couple weeks later. So I look up in the phone book. I said, “Yeah, I’m going to call her up.” So there it is, right in the telephone, 419 Redgate Avenue, Norfolk, Virginia. I called her up. I said, “Can I speak to Sylvia?” “No, she’s not in.” “Miss, is she coming back this afternoon?”

She said, “No, she’s not coming back. She went to school yesterday.” I said, “Where?” “Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia.” I said, “Do you have her dorm number or anything?” She said, “No, she just went there. Just went last night.” So I said, “Oh my God. I’m going to write her.” But that was stupid, to think, with orientation, new registration, and just a name –21, 22, I don’t know. So I wrote to her. One thing I can do is write letters. I love to write letters. Writing comes very easy to me, and I’m pretty good at it, too. So I wrote to her. In a million years I never thought she’d get it, the confusion – she got it. And a couple weeks later, she wrote back to me. I don’t know what she was thinking. What kind of jerk is this, trying to pick up somebody in temple? But she wrote. And I wrote back to her immediately. [LAUGHS] And then two weeks later, she wrote another letter.

But then I slammed the hammer down when I found out, on Thanksgiving – we were already in the end of October. On Thanksgiving, there was a formal dance, dinner-dance at the Officer’s Club. So I invited her for the dance. Lo and behold, she accepted. And when I picked her up that night, it was the first time she saw me, the first time I saw her. You couldn’t use the telephone; it was very restricted. Remember, I was at a port of embarkation, and that’s a very, very serious breach of security, to use the telephone. We weren’t allowed. When I saw her and picked her up, I knew then and there, that minute, that that was for me. She didn’t think so, but I did. So we had a wonderful night. And I didn’t see her anymore that Thanksgiving, but about a month later was Christmas break. Boy, I rushed the hell out of her. I don’t know, Christmas break must have been 10, 12 days. I must have seen her seven, eight times.

I knew. I was about 28 already. Yeah, I don’t know how old. I was going to marry that girl. And she went away. She went to school. I went down there once. It was 300 miles away. I took the 1:00 train in Norfolk to Christiansburg, Virginia. God almighty, I was worried when I got off the train how would I get to the college. There was one other man on the train with me. I didn’t know him, but we took a cab to the college. And I saw her for just one day. I had to leave the next day, because I had a two-day pass.

Each time I saw her reaffirmed what I thought. And then I went back to the base. Easter time, she came again. I was going to see her as much as possible. And then she had her prom at school, and she invited me, and I accepted it. I was on May 6th or 7th’45.

But the reason I mention that date to you – I went on the train; we get to Roanoke, Virginia, which is about another hour, hour and a half away, and the train must have been a 20-car train. And they had a bunch of MPs got on the train and were going around asking for everybody’s pass. I didn’t care. I had mine.

They come to me; they said, “Out, you’re the one we’re looking for, out.” I got a pass. “Out.” And you don’t argue with those guys. Guy must have been seven foot tall. I got out, and he tells me he had a telex from my office: return back to duty immediately. The reason is, after World War I, President – guys went crazy. They ripped up cities and everything, pent-up emotions, you follow me? President Truman vowed that would not happen after this. May 6 was a fake VE day. The Germans were reeling; they were ready to capitulate. But it was not formal. So I had to return. I called Sylvia. I said, you know, “I’m in Roanoke. But I can’t go to the dance.” “Why?” “I said, I just got a telex. I have to report back to duty.” She understood. And then that was May. And I planned on getting married in early September.

But my mother died about that time. So we had to postpone it to October. The wedding was on a Friday afternoon. At 1:00 I was still in the office, because there was still tremendous business there, not outgoing but incoming. I remember the ceremony was at 4:00 at the Army base at the Army chapel. At 1:00 I was still in the office. I said, “Major, I’m getting married.” He says, “Alright, yeah, I know. I know you’re getting married, but.” So I had a three-day honeymoon, but the honeymoon was unofficial. I had to call in periodically – I went to Virginia Beach. It’s only about 25 miles from Norfolk. And I used to call in until finally Tuesday came; I had to come back.

But I came back with what very few grooms ever had. There was a garden apartment being built in Norfolk, with the provision that they were built with steel and brick and all that, but every apartment had to be reserved for an Army officer at the Hampton Roads port of embarkation. And based upon that the builder built it. And the Army controlled the apartments. And I was quite a favorite there, because I was there about three, four years. When I got back, I had an apartment; it had everything – sheets, bedding, silverware, dishes, everything. You see, every officer that left had to leave it there, and they put a price on it and you paid that. So I walked into an apartment as anybody had, and it was a beautiful apartment.

I was a second lieutenant at that time, I got 150 dollars a month. A first lieutenant got 200 dollars. Then a captain – I became a captain – 250. And that’s it.

And I paid 60 dollars a month for a three-room garden apartment. And that included uniform laundry service.

So I started off my marriage there, and then I was released from the Army, and I moved back to New York immediately.. I had a Chevrolet car from the 1930s it ran pretty good. We loaded everything we owned and drove up with everything in the backseat. My sister lived in the Bronx, and she said, “It’s impossible to get an apartment now. But I have two kids”; we shared her apartment and she lived on 191st Street in the Bronx. And they had a garage underneath. So she arranged with the landlord that I could stay there. So the attendant there said, “Leave the key, so I can juggle your car around.” Very nice.

The next day, we had to go somewhere, so we go down to get the car – no car. I said, “What’d you do with it?” He says, “I don’t know.” “What do you mean you don’t know? You’re the one I gave the key to.” He says, “I don’t know.” He stole the car, with everything I had. I didn’t have a stitch of underwear. I turned it over to the police department. They said, “Where did he get the key?” I said, “I gave it to him.” He looked at me as if I’m nuts. In retrospect, I was. He had a logical request. He had to move it around. So that was my – debut. They never found the car again

No, I had nothing to do; he was the attendant in the garage. He was a car jockey.

PK: So you came back; you were living with your sister. And you didn’t have kids at that time, but you had to look for work. What kind of work did you find?

MURRAY FORER: Let me take you back to my commanding officer, who took a liking to me. He says, “I have two sons. I want to do something for you.” He says, “I can’t take you into our business. But I will set you up with my two sons and build you a hosiery mill..” He was my commanding officer,. Ira Schey. He was originally from New York,

a multi-millionaire. He lived at a Westchester Country Club, the Hampshire House, and he had a 400-acre estate in Charlottesville, Virginia. I went up to see him. “That’s what I want to do for you.” I said, “Boy, I’ll accept it.” And he gave me a little piece of it.

He built me and the sons a brand-new mill, as current and as new as tomorrow’s newspaper. It was in Lenore, North Carolina, All hosiery mills were down there then.

They couldn’t unionize anybody in North Carolina. The governor was anti-labor.

Irv Schey’s main factory was Valdez, North Carolina, which is eight, ten miles away. It was a massive, three-acre – I don’t know how – And the business was Ladies’ hosiery

He says, “Only go into a business that you know.” And I learned that as fact. But the reason that Lenore – that’s only eight, ten miles away, and they owned a plot in Lenore, North Carolina, so we used it. So we built a brand-new mill, brand-new equipment, and he put up the money, which was a big number. But that, to him, was petty cash. One son stayed in the mill. One son came up here with me.

We ran it from a New York office and the guy down there ran the factory We shipped direct. We got the orders sent down and they sent it to –anywhere in the world. It turned out to be pretty good. But later on it became a disaster.

I stayed with my sister, I would say, three, four months. She had a home in Long Beach. Unheated, but it was a summer home. So after a while, she says, “You can go out to live in that house,” which we did. But then it got bitter, bitter cold. So I said, “I got to get out.” But one of my friends from the Bronx was a builder. His name was Harold Derfner.

He was building apartment houses. I said, “Harold, I need an apartment.” He says, “The first vacancy we get, you have.” I had gone to Evander with him.

And he fulfilled that promise. He got me a beautiful, beautiful apartment in Forest Hills. He owned the building. It was ’46. At 60 dollars a month rent, elevator apartment on the sixth floor, beautiful. And inflation began, so they raised us to 66 dollars. Now you couldn’t get a closet. But it was beautiful. I enjoyed it. Sylvia enjoyed it. We lived there about three years

But we knew we were going to have a family. So I wanted to move out of there before. My sister that I lived with moved to Great Neck, too. She said, “Look in Great Neck.” And we did. And fortunately, we found a plot, no house but the guy had plans. So Mr. Raddick, his name was, I liked that. He says, “It’ll be built within six months. Less. Less.” So I took it. I took it from a plan. But this was the house he built.

How much it cost? I think about $30,000. But then we put a lot in it. We’ve got a finished basement.

The house was finished in ’47 No I was wrong. My first child was born when we still lived in Forest Hills. My second child, we moved from the hospital to here. Both girls, wonderful.

You know, I’m the richest man in the world to have the family that I have, two daughters and three grandsons. They call me all the time. They got along beautifully with each other. It’s unbelievable. And people tell me how lucky I am. I’ve had a very charmed life. I had the most wonderful, wonderful Cinderella marriage for 63 and half years. Do you know I didn’t have 63 cross words in 63 years? Unbelievable. My wife passed away 2/26/06.

PK: Going back to your business. did you stay with that company, with Schey in Lenore?

MURRAY FORER: Right to the end. No, I just misled you there. I stayed with them – let’s work backwards. I stayed with them until 18 years ago. They got too smart for themselves. They had sticky fingers, and I’m in New York and they’re down in North Carolina, and it began to shrink without any reason. You didn’t have to be a Rhodes Scholar to know that they were doing some backdoor selling.

So that’s not for me. Honesty, to me, is paramount in anything I do. If you can’t do it legally, I can’t do it at all. So I left them. I left on that one day, and the next day I got another job.

PK: You had a piece of the business, did they buy you out?

MURRAY FORER: The money disappeared. Oh, no, that wouldn’t have happened if the father was still alive. To me, I was more of a son to him than his sons.

:But I got right back into the same business and I did quite well for myself. Banff International was the company. I utilized all my contacts. And they trusted me implicitly. I worked with somebody, but I was almost on my own. I’d make my own deals and all. And I did quite well, for them and for myself. The chairman of the board was very good to me. But he passed away. And when he did, his two son-in-laws – talking about sticky fingers, oh, brother. I don’t go for that. So I left them. And I got my last job, with Regent International. That was a big business at 1411 Broadway. I did well for myself and for them. And I worked until last October. And I always vowed to myself, anytime I get up in the morning that I don’t want to go to work, that’s the day I’m quitting. And that morning, I said, “Oh, I don’t feel like going to work.”That’s last October. I was working until last October, full-time,Used to take the train, just like any other nut.

The last year when I was 94, my daughters didn’t want me to take the train. “What the hell are you doing? You’re crazy.” So I took a car service, door to door, for I guess a year. Then I quit.

PK: Okay, let me go back a little bit now to the 1930s. You were a young man then; it was before the war. Did you have interest in baseball or sports? What were your interests?

MURRAY FORER: I knew more about baseball than anybody in the world. I was a Yankee fan, still am. Yeah. I knew every player’s name, number, position, salary. [LAUGHTER] I don’t care anymore. But I still am a very, very enthusiastic baseball fan.

I used to go to Yankees Stadium when it cost 55 cents for a seat in the bleachers. And 10 cents for a hot dog. Ruth, Gehrig, Musial, Joe Dugan, Tony Lazzeri. I know them all.

But even now, the first thing I do when I get the paper delivered to me, I look at the sports results. And I get sick when I know how badly the Mets are doing, yuck.

PK: Tell me about some of those friends that you made during your lifetime, your close friends.

There was eight of us– some of them I even knew from public school; one of them I knew from sixth grade to Evander Childs to undergraduate to law school. And many of them – Alan Sherman. We were all very close. The wives were very close. We’d go to each other’s homes periodically. slowly but surely to the last. I even went to their funerals

The last one was a professor at NYU. He started with me, being a librarian, making 20 cents an hour. He used to work after school at the New York Library. And after a while he got very interested in library science. He became the librarian at NYU. He used to be a librarian consultant. His name was Jule [LAUGHS] I forget. All those friends were from the Bronx.

PK: Tell me – you were born in 1914.

MURRAY FORER: Exactly.

PK: Okay, so in 1924, when you were ten years old, Warren Harding died. Do you remember that?

MURRAY FORER: That’s right, yes. Just a minute. I lived in Trenton. And I remember, during the night, paperboys used to call out, “Extra! Extra! President Harding died!” They don’t have that anymore. [LAUGHTER] But that’s the only time that I remember anybody calling “Extra! Extra!” That’s it.

PK: Now, tell me what you thought of Roosevelt and where you were when he died.

MURRAY FORER: When Roosevelt died, I was going to see Sylvia for dinner that night. And I’m waiting on the corner. in Norfolk And in Norfolk, if you’re in uniform and you stayed on a corner one minute, there’d be ten cars picking you up.

And I was waiting on the corner of Hampton Boulevard to go with Sylvia. And some car drove by with his radio on or something. It said, “President Roosevelt died.” I think he died in the afternoon; I don’t – he died before I knew he died. That was a very traumatic affair. I was very supportive of Roosevelt. I voted for him each time. I felt he was a very excellent president. When he first took office, every bank was on the verge of going bankrupt. And to stem that possibility, he closed every bank in the United States. You couldn’t cash a check if you stood on your head. Because he wanted to give them time to stabilize, to get this – fear under control. Even what few dollars I had in the bank, I was wondering if they’d have a run on the bank. Bank of the U.S. used to have people around the block. Nobody had any money, but they all wanted their 100 dollars, 200 dollars, 300 dollars.

You know, I’m talking reality. 200 dollars now is enough to pay a cup of coffee.

But I like Obama very much. The one thing I worry about: that debt. I think that he’s on the right track. This country was on the verge of going bankrupt. The country, I don’t mean individuals.

That other guy, Bush,ugh. He’s going down in history as the worst.

I never had a headache, I never tasted alcohol , never even had a cup of coffee. When my daughter got married everyone had champagne. They gave me a glass of ginger ale, it looked like champagne. Like I told you before, I’m the richest man in the world.