Comfortably superficial

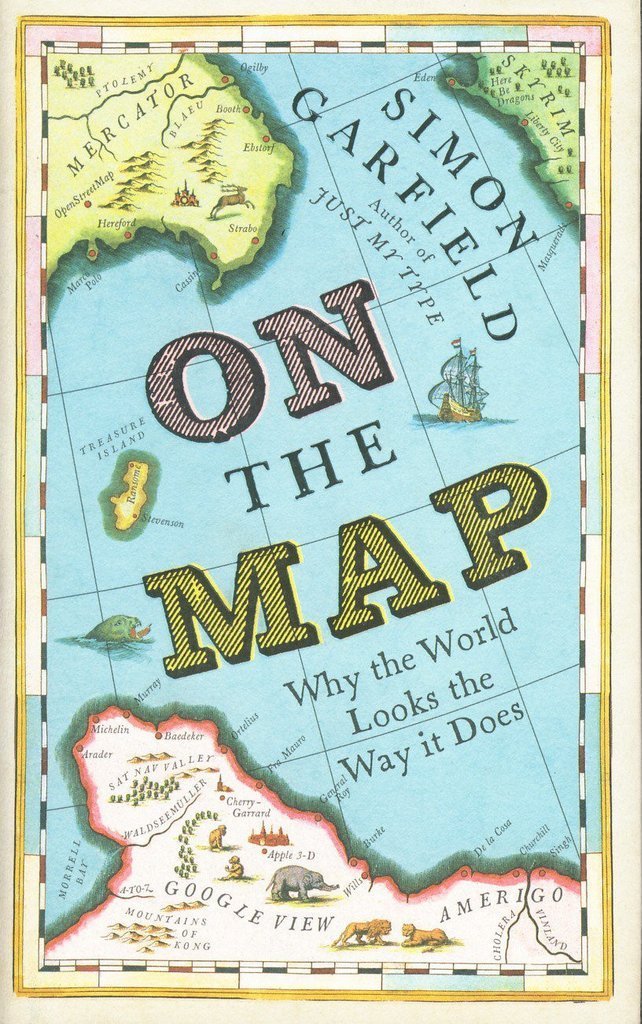

Maps have been a growing obsession of mine, particularly in the course of my peregrinations through the domain of fantasy fiction, but I haven’t read anything much about them, or about the history of cartography. Had I decided to do so, I would probably not have begun with a mass-market book like this one, but I received Simon Garfield’s On The Map as a gift, and stuffed it in my bag for a spot of light holiday reading. As such it was an entertaining companion, and many of its cartographic tales will find a lasting place in my recollection; it makes few demands of its reader, and offers the kinds of reward that are not hard-won, but serve as a more than adequate decorative frill for days spent rising late and lazing around on the Landmark Trust’s exceedingly comfy sofas. Having read it I am now apprised of the existence of a number of important maps, the names of some prominent map-makers, and some impressions regarding the historical development of cartography. However, that developmental narrative is something I have assembled for myself from various accounts in the book, and is thus extremely provisional, given that On The Map is a work of journalism rather than scholarship. There’s nowt wrong with journalism, and I have a great deal of admiration for some examples of journalistic writing, but there is also no reason why a journalistic account cannot convey some form of intellectual synthesis, and this is something in which Garfield signally fails. His book is essentially a chronology of anecdotes, interesting and frequently amusing anecdotes, but fragmented and seemingly disconnected observations nevertheless. It is one of the great fallacies of the writing of history that there is a single stream of important events that the scholar can tie together in a chain of causality, and I have no objection to an account that eschews such a reductive simplification, but there is no attempt here to relate events to confluences and divergences of cartographic theory and practice: Garfield simply tells us that X happened, and that then Y happened. As such, his book is about twice as long as it needs to be. Despite the helpful inclusion of a bibliography and index, it is unlikely to be of much use to anyone with a serious interest in the topic, and as a superficial but entertaining tour, it feels flabby and long-winded. Two-hundred and fifty pages of this would have been adequate, and the requisite editing would have demanded a rigorous focus on the really fun stuff, as well as offering an incentive to sharpen up the prose. I certainly enjoyed reading this book, but I wouldn’t give it any more credit for that than I would the sofa I was lying on.