A thick slice of life

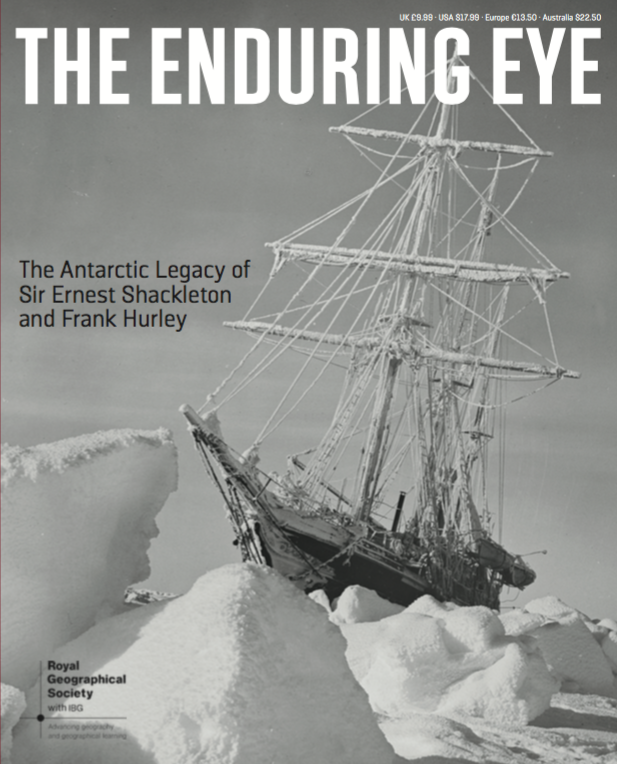

We were killing time between shows at Edinburgh Fringe when we wandered into the National Library of Scotland (because, well, libraries), and came across an extraordinary touring exhibition from the Royal Geographic Society’s photographic collection, entitled Enduring Eye. The pictures (and some movie footage) were shot by Frank Hurley, the expedition photographer on Ernest Shackleton’s ill fated trip to the Antarctic, and they document that legendary quest in a level of detail that I had never suspected existed. Given the privations endured by the expedition team, the months they spent living under a lifeboat, and dragging essential supplies on sleds, it’s pretty extraordinary that they preserved any photographs at all, but judging by this exhibition they seem to have kept them all. The long sea voyage south, the many months of life aboard ship while the Endurance was trapped in the ice, and all of the subsequent events are documented in exquisite detail: there is even dramatic movie footage of the final demise of the Endurance, as the ice crushes the ship’s last remnants into matchwood. Despite their legendary sea voyages to Elephant Island and then on to South Georgia, and the epic tale of heroism and survival, it is perhaps the depictions of life aboard the immobilised Endeavour that I found the most notable: there is something immeasurably touching about the domestic existence of these men, with its small jollities, its routines, its infinite forbearance and optimism. The amazing fact that no lives were lost on this expedition is bittersweet: the crew and explorers returned in good shape, and in good time for some of them to give their lives in the paroxysm of brutality that swept Europe between 1914 and 1918. The RGS’s photographic archive has been digitised, and many of the photos in this show are displayed at a far larger size than they could be practically printed from Hurley’s negatives: the display is immersive as a result, and the accompanying text is both informative and unobtrusive (although it would take an extreme degree of curatorial importunity to get in the way of such extraordinary images). This is an exhibition well worth seeing, but if that’s not possible, I can equally recommend the accompanying book. One of the most intense moments of human endurance and companionship is documented here with an immediacy that the age of social media has come to regard as proper to its own time: we may live in the Instagram era, but some photographers saw the potential of their craft to preserve and communicate experience long before that became the common coinage of social life. Frank Hurley was one of them.