The Gathering Storm: Beginnings of the Communist insurgency and Moro secessionism in the 60s

We turn back to the ‘60s. Underneath all the firestorms of public opinion against Ferdinand Marcos in his first term as President of the Philippines was the brewing corruption in almost all levels of government. This was beyond a doubt, as evidenced by numerous news weeklies of the time. And this only fed the fire that had taken the form of the beginnings of a Communist wave in the country, which Marcos saw as one of his justifications for his planned Martial Law.

When Marcos won in the presidency in 1965, so much have been promised. Immediately there was a boom in infrastructure projects. Marcos made sure that a number of public schools and roads were built. The Cultural Center of the Philippines, proposed during the campaign by Imelda Marcos, would be realized with the issuing of Executive Order No. 30, s. 1966, with the establishment of the center’s Board of Directors, all of whom, when in the position, voted (or pressured to vote?) for Imelda Marcos as chairperson. It was the beginning of what critics of the Marcos administration would call the “Edifice Complex.” Here was when Marcos honed his ability to use created space and structures to perpetuate the illusion of progress and power. Much of these infrastructures, especially during the period of Martial Law, was funded largely by foreign loans, with most earnings and war reparations received diverted to corrupt government officials, including that of President Marcos.

*First Lady Imelda Marcos poses in front of her pet project, the Cultural Center of the Philippines, designed by architect Leandro Locsin (circa late 60s). Imelda said in April 1998: “I was born ostentatious. They will list my name in the dictionary someday. They will use ‘Imeldific’ to mean ostentatious extravagance.” Source: Arkitektura.Ph.

With much protestation from the adversary of Marcos in the Senate, Senator Ninoy Aquino, the rampant excessive government spending and lavish parties were pointed out, to Malacañang’s chagrin.

Moreover, there was the backdrop of the Vietnam War. The Vietnam War was a byproduct of the communist scare that spread around the Western world in the late 50s to the 70s.

I must then take a pause to define what is Communism, and the brand of communism that took root in the Philippines.

Communism, proposed by German philosopher Karl Marx, is a political philosophy simply stated that it is through labor that we the People, or the Workers, produce and express our true humanity and dignity as human beings. However, “urbanization” and “industrialization” taking the form of Western intrusion on Asian affairs (Imperialism) exploit the people’s productivity and therefore their dignity. It is therefore the goal of communism to resist these imperialist forces and encourage “class struggle” to establish a communist society—one that is defined by common and equal share of ownership of production, effectively abolishing all social classes—no oppressive “mayaman” and no oppressed “mahirap.”

I won’t dwell with my disagreements of this worldview (that takes another blogpost), but one can see how the Filipinos, especially those of the middle class and the poor, and those who study and were witnesses to social realities in a wide angle of academic inquiry—the college students—were ready captive audiences to this utopian philosophy. The abuse of the Philippine Constabulary on the student protesters that were regularly seen in the news, side by side with the pomp and pageantry of government officials and the Marcoses only validated the communist cause in the activists’ eyes.

The proposal of President Marcos to send Filipino troops to their deaths to help American troops push back the Communists of North Vietnam and defend the democratic South Vietnam was all over the news in 1966. The reason implied by Marcos was for the U.S. to continue sending financial aid to the Philippines and for the American protection of the Philippines against communist insurgency not to be withdrawn (At this time, Clark and Subic remained U.S. Bases since 1946). And yet by this time, even the American public opinion had shifted against this costly U.S. intervention in Vietnam altogether, while the U.S. government refused to pull out because it did not want to lose face.

*American protesters against the Vietnam War assembled outside the United Nations Building in New York City, 1967.

*The Pulitzer winning photograph that became a haunting image of the Vietnam War, the 9-year old “Napalm Girl” Phan Thị Kim Phúc, runs naked with burns, fleeing to safety after South Vietnamese forces dropped napalm bombs on the village of Trang Bang in Vietnam. Photographed by Nic Ut on June 8, 1972.

As Walter Lippman, quoted by Teodoro Locsin Sr. of the Free Press, stated:

“What is the root of all this swelling anti-Americanism among the Asians? It is that they regard our war in Vietnam as a war by a rich, powerful, white, Western nation, against a weak and poor nation , a war by white men against non-white men in Asia.”

And yet despite all this was Marcos’ proposal that would eventually push through with the formation of the Philippine Civic Action Group (PHILCAG).

*The PHILCAG in Tay Ninh, Vietnam, circa 1966-1969. Source: Philippine Defense Forces Forum.

It was here where Marcos began to be framed in the protesters’ lens as “tuta ng Kano” or puppet of the Americans. Indeed, as we would see, Marcos did not merely become a pawn, but rather he negotiated his way to get what he wanted. He would push the envelope, to see how the Americans would react if he imposed his so-called “constitutional authoritarianism.” But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

The pulse of the young student activists in the late 60s, numbering to the thousands rallying to the streets began in small pockets. Like fire fed by old corroding wood, the fire would spread uncontrollably, and it became more vocal and even more violent.

*One of the largest leftist youth groups, the Kabataang Makabayan threw stones and softdrink bottles on the police that had just clubbed some protesters. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

Journalist Pete Lacaba immortalized the placards raised during these violent demonstrations by including it in his reportage via the Philippines Free Press. The placards had the texts: “No more aggression thru Philcag”; “A puppet can never be great”; “Johnson - Modern Hitler”; “Philcag - imperialist tool”; “Marcos and Crisologo - Iloko warlords”; “Ang Pilipino muna”; “Pauwiin ang Philcag!” A letter sent to Manila Times aptly described the popular sentiment then, dated January 1968:

“Life is so difficult nowadays. One ganta of rice costs over P2; movie prices have gone up; one small calamansi is worth 5 centavos. Even a trip to Baguio is now more costly; toll fees have been jacked up from P2 to P4.

“The Marcos administration is to be congratulated for its success in making the people believe that the situation is not as difficult as it really is. The President’s bright boys talk of ‘miracle rice’; but has the price of rice gone down? They build a Cultural Center; but, does this alleviate the plight of the poor? They plan grandiose state visits; but, will these visits make life a little more bearable? What the people need are bread and butter, not circuses fit for kings!”

It was a common sight then to see young men and women assembled with placards in front of the U.S. Embassy in Roxas Boulevard, Manila, marching towards the Manila Hotel (a stone’s throw away), the Legislative Building (a short walk from the embassy to Luneta) or Mendiola at Legarda, and Plaza Miranda in Quiapo.

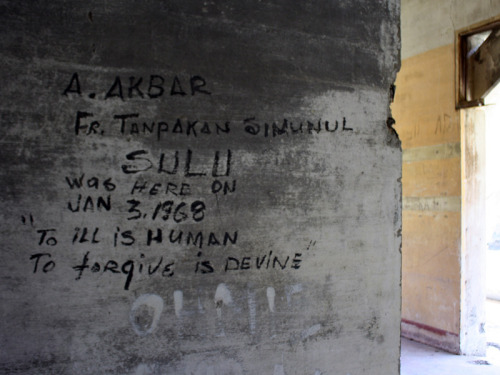

*The Jabidah trainees left graffiti on the walls of an old abandoned hospital in Corregidor Island which can still be seen today.

As protesters snowballed from the concluded Manila Summit of 1966 onwards, leading to the founding of the Communist Party of the Philippines in 1968, another issue was brewing. Following President Diosdado Macapagal’s initiative of reclaiming Sabah under Philippine sovereignty, President Marcos moved up the ante and secretly initiated Project Merdeka (meaning “freedom” in Bahasa, the language in Sabah) in 1967, authorizing Major Eduardo Martelino to lead the covert operation codenamed “Jabidah” with the sole mission of destabilizing Sabah and forcibly invading it, grabbing the opportunity of an unstable Malaysian federation. Around 180 Tausug and Sama men underwent reconnaissance training initially in Simunul, Tawi-Tawi, and were transferred to further train in jungle warfare training at Corregidor Island by December 30 of the same year. After months of harrowing training on the island without being paid, and having slept on ipil wood and cot, as high-ranking officers were billeted to Bayview Hotel in Manila, around 62 of them sent a secret petition to President Marcos to complain about their plight. After this, Martelino met with the petitioners and assured them of their pay. They were subsequently given immediate comfort. However, on March 1, 1968, all of the signees of the petition were considered resigned. Moreover, 60 to 70 trainees were said to have been moved to Camp Capinpin, Rizal. By March 15, another batch of 24 men of the operation were removed from Corregidor, and then another batch followed on March 18, 2:00 am. Then another batch at 4:00 am. Jibin Arula, the survivor, recounted, that his batch was requested to ride a military truck accompanied by armed men, to Corregidor airport. When they reached the airport, they were asked to get down from the truck and line up. Only the did Arula heard of gunshots as one by one, his colleagues fell “like dominoes.” He ran as fast as he could, and swam from Corregidor to Caballo Island, where he was rescued by two fishermen.

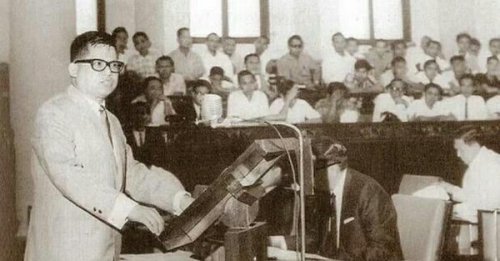

*Senator Ninoy Aquino delivers the speech, “Jabidah! Special Forces of Evil?” in the Senate Session Hall of the Legislative Building (now National Museum) in Manila, March 28, 1968. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

Senator Ninoy Aquino exposed the whole cover up on the Senate floor on March 28, 1968, to the shock of the political establishment, the media and the Marcos administration. The privilege speech was just an allegation, Marcos said, used by the opposition to discredit him. The massacre is contested until today in that Aquino was said to only have corroborated the account as divulged by Arula and by use of his journalistic deductions. However, the question remains, it this was all a ruse, how come it was enough for many of the key military men in the “massacre” to be court-martialed in that same year?

The issue was largely publicized by the media, incurring condemnation from the international community. In response, Malaysia severed its diplomatic ties to the Philippines, with much negotiation from Marcos’s end to restore it.

Two months after the massacre, in reaction to the injustice done on Jabidah men, on May 1, 1968, former Cotabato governor Datu Udtog Matalam established the Muslim Independent Movement, the first organized secessionist group in Mindanao, and a precursor to the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), which would be founded in October 1972, a month after the declaration of Martial Law.

In conclusion, much of the Mindanao conflict and the leftist insurgency that can still be seen today were largely due to the pre-Martial Law Marcos administration—the disregard for social welfare, the excessive use of force against protesters, the cover ups on corruption allegations, vis-a-vis the show of extravagance and wealth of the First Family. We would soon find that the leftist protests would gather steam and find its greatest expression in what would be known in Philippine history as the First Quarter Storm of 1970.

The Road to Martial Law is a series of blog posts documenting the unprecedented rise of a Filipino dictator and the sudden death of Philippine democracy with the declaration of a nationwide Martial Law via live television on September 23, 1972.

The Road so far:

- It Takes a Village to Raise a Dictator: The Philippines Before Martial Law

- Truth or Dare?: Marcos during WWII

- The Turbulent ‘60s and Marcos’ Ascent to Power

- The Gathering Storm: Beginnings of the Communist insurgency and Moro secessionism in the ‘60s

- The First Quarter Storm of 1970: The Philippines on the Brink

- A Plan for the Endgame: Plots, Protests, Scandals and Assassinations

- Pawns in Cities lobbed with Bombs: Events leading to the Plaza Miranda Bombing

- Hijacking Democracy: The Mood before the Declaration of Martial Law

- September 21, 1972: When Martial Law Had to Wait for One More Day

- Like a Thief in the Night: Martial Law Implemented on September 22, 1972

- The Long Night Begins: Martial Law Announced on Live Television, September 23, 1972

- A Mere Scrap of Paper: The Constitutional Convention Hijacked under Martial Law

- The Final Blow: A compromised Supreme Court legitimized Martial Law

- Road to Martial Law Redux: A Conclusion to a Series

Photo above:

Protesters protect student Rene Ciria Cruz from arresting officers at the U.S. Embassy, December 29, 1969 (Source: Jose Lacaba, “The First Quarter Storm was No Dinner Party”)

Bibliography

___, “Dissenting Opinion: Don’t Go to War,” Philippines Free Press, March 12, 1966, link.

___, “Gaudencio Antonino: Man of the Year, 1967,” Philippines Free Press, January 6, 1968, link.

___, “Eduardo L. Martelino, et al, vs. Jose Alejandro et al.”, G.R. No. L-30894, March 25, 1970.

___, “Jibin Arula vs. Brig. Gen. Romeo C. Espino, members of the court martial, et al.”, G.R. No. L-28949, June 23, 1969.

Aquino Jr., Benigno S., “Jabidah! Special Forces of Evil?”, Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines, March 28, 1968, link.

Hicks, Peter. The Journey So Far: Philosophy Through the Ages. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2003.

Lacaba, Jose. Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage: The First Quarter Storm & Related Events. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing, Inc., 2003.

Liang, Dapen. Philippine Parties and Politics: A Historical Study of National Experience in Democracy. San Francisco, The Gladstone Co., 1970.

Lico, Gerard. Edifice Complex: Power, Myth, and Marcos State Architecture. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2003.

Robles, Raissa. Marcos Martial Law: Never Again, Student Edition. Quezon City: Filipinos for a Better Philippines, Inc., 2016.

Tolentino, Arturo. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Publishing House, 1990.

72 Notes/ Hide

marlborored3000 liked this

marlborored3000 liked this mannyjacintos liked this

maria-sinukuan liked this

maria-sinukuan liked this the-martial-law-thingy reblogged this from indiohistorian

scaleehsi reblogged this from tigerbalmproject

scaleehsi liked this

utot-atbp liked this

doubletak-e liked this

hearteyesroseskies reblogged this from tigerbalmproject

ensaybinibini reblogged this from ruscano

theredwitchgirl liked this

ruscano reblogged this from indiohistorian

ruscano reblogged this from indiohistorian  ruscano liked this

ruscano liked this takerusato liked this

tambis reblogged this from blushnhoney

azirine liked this

azirine liked this travelingdorks liked this

moggy-mog liked this

blushnhoney reblogged this from tigerbalmproject

never-ever-ever-again-stuff-blog liked this

gardenwhosmellsgood liked this

gardenwhosmellsgood liked this howlshair liked this

wozziebear reblogged this from indiohistorian

swirlsofblackandwhite reblogged this from indiohistorian

swirlsofblackandwhite reblogged this from indiohistorian enriquezaldo liked this

hopeful-transmissi0n reblogged this from indiohistorian

hopeful-transmissi0n liked this

disasthrum liked this

bulletproofbirbmom reblogged this from indiohistorian

mr-bottle-28-3-96 reblogged this from indiohistorian

hearteyesroseskies liked this

mr-bottle-28-3-96 liked this

mackanikalartisan reblogged this from tigerbalmproject

rustyneedle liked this

bel-chiaro-di-luna liked this

bel-chiaro-di-luna liked this tigerbalmproject reblogged this from positivelyasian

historicity-was-already-taken liked this

historicity-was-already-taken liked this criolloylapeninsula liked this

foolcircle liked this

icecoldtea liked this

- Show more notes