Like a Thief in the Night: Martial Law Implemented

September 22, 1972. President Ferdinand Marcos, ever the paranoid leader, never revealed his plans for Martial Law to his close associates, except to a selected few, many of whom were within his inner circle of advisers.

Take for example that morning. House Speaker Cornelio Villareal was bound for Moscow, when he dropped by Malacañang to see the President. Villareal asked him bluntly, “What is this report that martial law will be declared?”

President Marcos only replied, “Don’t mind those false rumors.”

The same thing was said to Marcos’s very own Executive Secretary, Alejandro Melchor. Melchor was being sent by Marcos to the United States for the World Bank meeting at that time. But before he left that morning, he submitted a memo to the President, objecting to any possible plans for martial law. Marcos assured him, however, that whatever his plans were but for the good of the country. Marcos even revealed that he might migrate to the United States himself after his term. Melchor, feeling assured, then left for the U.S in the evening.

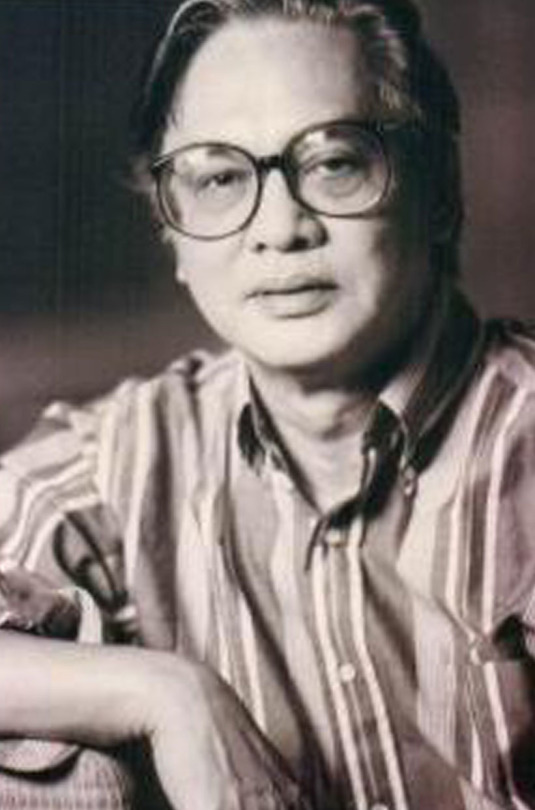

President Marcos’ own speechwriter, the Palanca awardee Adrian Cristobal, never got wind of the plans to impose Martial Law that night.

That Friday night, September 22, I was packing my bags. I was all set to fly to Argentina the following day. I saw Marcos that morning, and he was effusive. ‘O make sure you study Peronism, ha. We may need something like that before my term expires.’ I said ‘Yes, Sir.’ And I meant it. I really thought he wanted a study like that.

*Adrian Cristobal, awarding winning writer, and President Marcos’s speechwriter. Source: Philippine Daily Inquirer

In the media, the fear of martial law was evident. Teodoro Valencia, writer of the Manila Times, released an article on that day, and weighed in on what Martial Law would mean for the people.

Nobody wants martial law. Not even the closest friends of the President would wish it. Once martial law is imposed, the military becomes the power. Laws won’t protect anyone. Those of us who have experienced martial law twice in our lifetime can’t imagine another one. Young people toy with the idea by taunting the government into doing it, they don’t know what they’re asking for.

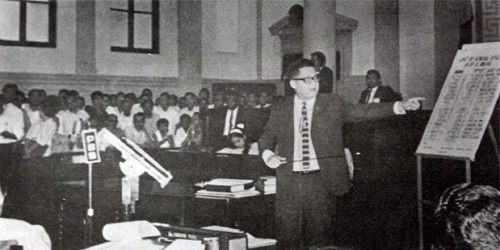

In the Senate, to Senator Aquino’s disappointment, the Senate junked its probe on the Oplan Sagittarius, putting the issue to rest. Aquino was delivering a speech then to the students of the Asian Institute of Management when he received the news. He expressed his doubts when he told the students, Marcos “would not dare declare Martial Law.” Meanwhile, as noticed by Senator Jovito Salonga, the usual press statements coming from Malacañang have ceased.

*Senator Ninoy Aquino, President Marcos’ most outspoken critic in the Senate, delivers his speech on the Senate floor, “A Garrison State in the Make,” on September 21, 1972. Source: Internet Archive

At 5:00 p.m., according to Enrile’s own account, he met with Brigadier General Mario Espina of the Philippine Constabulary, to plan the movement of the military across Metro Manila without raising any alarm. The secrecy of the implementation of Martial Law was of utmost importance. They were all on standby, as the President may send the orders anytime soon.

At 6:00 p.m. the long wait was over. Defense Secretary Enrile received a call from Marcos, giving him his go signal. A few minutes later, Major Roland Pattugalan, presidential aide-de-camp, delivered three large sealed envelopes to Enrile’s office. The envelopes contained all the prepared documents from last year, all signed by Marcos with the seal of the President. According to Enrile, these are: (1) Proclamation No. 1081, (2) 7 General Orders, (3) 7 Letters of Instruction.

Note that Proclamation No. 1081, placing the entire country under Martial Law, was not countersigned by Executive Secretary Alejandro Melchor, and Assistant Secretary Ronaldo Zamora, both of whom were out of the country.

Pattugalan, upon handing Enrile the documents, said:

The President wants you to convene the Chief of Staff, the J-Staff and the commanding generals of the army, the constabulary, the air force and the navy. The President wants you to tell them that the operation shall proceed as scheduled and that starting tonight at nine o’clock the country will be under Martial Law. The President instructed me to tell you that you will supervise the operation and that he will be in the Palace and available anytime for consultation if there is a need for you to consult him.

By 7:00 p.m., Enrile went in person to the General Headquarters of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and instructed military commanders of the President’s instructions.

At around 8:00 p.m. at Notre Dame Street, Wack-Wack Village in San Juan, the convoy of Enrile passed by. According to Enrile:

My convoy drove out of Camp Aguinaldo through Gate 2 in front of Camp Crame […] When my convoy was driving through Wack-Wack subdivision, a speeding car rushed and passed the escort car where I was riding. Suddenly it opened several bursts of gunfire toward my car and sped away.

Luckily, my driver and my military aide, Tirso Gador, who was seated beside the driver were not hurt […]

My convoy left my wrecked car on the road and returned to Camp Aguinaldo.

The supposed ambush on the Defense Secretary was the tipping point, the reason President Marcos put for declaring Martial Law. But there is more to the story than that simple ambush.

Oscar Lopez, one of the Lopezes and a resident of the high end subdivision recounted:

You could say that the declaration of Martial Law began right in my backyard so to speak …. That night, I was with my children in the family hall of our house [Notre Dame Street, Wack Wack Village]. Then all of a sudden, we could hear a lot of shooting outside. We didn’t know what was happening. After the shooting died down, I went out. I took a peek at what was happening outside my fence and I saw this car riddled with bullets. Nobody was hurt; there was no blood. The car was empty.

Our driver happened to be bringing our car into our driveway at around that time, so he saw the whole thing. He told me that there was a car that came and stopped beside a Meralco post. Some people got out of the car, and then there was another car that came by beside it and started riddling it with bullets to make it look like it was ambushed. But nobody got killed or anything like that. My driver saw this. He was describing it to me.

Vergel Santos, biographer of Chino Roces, writes his doubts on the alleged ambush:

Secretary of National Defense Juan Ponce Enrile was ambushed in a car that did not convey him at the time and his driver, the only rider escaped untouched by any of the numerous and closely bunched bullets that hit it. The car, a black, V8-powered LTD by Ford, an emblem of official and political power at that time, was left at the scene, on Notre Dame Street, in the old upper class enclave of Wack Wack …

[…] Why inside a village and not on a public street, and why in that particular village? Possibly for easier stage-managing: the family of Enrile’s sister Irma and her husband, Dr. Victor Potenciano, lived there, in Fordham, the next street in the Potenciano home and got the story straight from him, as officially scripted.

Ramon Montano, a Philippine Constabulary general who led the investigation on the ambush, revealed:

“It was fake. I don’t know who faked it but the ambush was fake because when we arrived at the scene of the crime or reported crime I found out that the bullet holes were all neatly aligned. Neatly aligned.”

Primitivo Mijares, the former pressman of Marcos and a victim of forced disappearance, would claim that the ammunitions confiscated at Digoyo Point would actually be planted on the said ambush to link it to the Communists.

Curiously enough, Enrile would admit in the 1986 press conference declaring his withdrawal of support from Marcos, that this ambush was actually staged to give legitimacy to President Marcos’s declaration of Martial Law. He had since flipflopped that testimony in recent years.

At the time of the ambush, Marcos instructed General Fabian Ver to have a security cordon around Malacañang. Mijares, who was there at the Palace, described that the President “was barking orders all over the place.”

At around 9:00 p.m. Marcos issued the orders, as lights to liberty and accountability were shut down one after the other.

Proclamation No. 1081, declared that the Philippines was under the state of Martial Law.

General Order No. 1, declared to the AFP, that as Chief Executive, Marcos was already assuming both the Executive and Legislative powers of government, wresting the latter from Congress. Marcos asserted his authority on the entire government, and all “agencies and instrumentalities.”

General Order No. 2 authorized the military to arrest all the people included in the list of personalities deemed part of a “conspiracy” to seize power from the President. The list included approximately 8,000 individuals. Noteworthy were journalists Chino Roces and Max Soliven of Manila Times, Teodoro Locsin Sr. of the Philippines Free Press, Hernando Abaya, Luis Mauricio of the Graphic, Luis Beltran of Evening News, Amando Doronila and Ernesto Granada of Manila Chronicle. Among the senators to be arrested were Senators Ninoy Aquino, Jose Diokno, Ramon Mitra Jr., Soc Rodrigo. Among the ConCon delegates were Napoleon Rama, Enrique Voltaire Gazmin and Jose Mari Velez. Others were Veronica Yuyitung, Ninotchka Rosca, Alejandro Lichauco, Jose Concepcion and Jose Noledo. Four days later, this order would be amended to include shady provisions such as “crimes against public morals.”

Letter of Instruction No. 1 authorized the military to seize and shut down all private media (papers, magazines, radio and television. This provided the immediate shut down of 16 dailies, 3 business publications, 1 news service, 7 TV Stations, 66 community-run newspapers, and 292 radio stations.

Letter of Instruction No. 2 authorized the military to take over public utilities that include Manila Electric Company (MERALCO), the Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company (PLDT), the National Waterworks and Sewerage Authority (NAWASA), the Philippine National Railways (PNR), the Philippine Airlines (PAL), Air Manila, Filipinas Orient Airways, and “such other public utilities which, in your sound judgment, you consider essential for the successful prosecution by the Government of its effort to contain, solve and end the present national emergency.”

This were supplemented by General Order No. 3, transferring all challenges to martial law from civil to military courts, and General Order No. 4 imposed a nationwide curfew from 12 midnight to 4 a.m. Those who violated the curfew would be arrested.

At around 9:55 p.m. Marcos took the time to scribble on his diary:

Sec. Juan Ponce Enrile was ambushed near Wack-Wack at about 8:00 pm tonight. It was a good thing he was riding in his security car as a protective measure. His first car which he usually uses was the one riddled by bullets from a car parked in ambush.

He is now at his DND office. I have advised him to stay there.

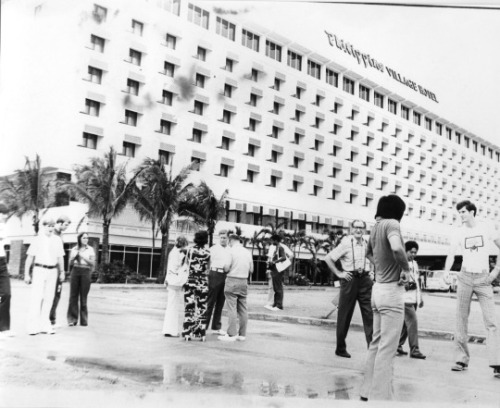

And I have doubled the security of Imelda in the Nayon Pilipino where she is giving dinner to the UPI and AP as well as other wire services.

This makes the martial law proclamation a necessity.

*The Philippine Village Hotel in the 70s.

Meanwhile, at 10:00 p.m. First Lady Imelda Marcos arrived at the Philippine Village Hotel at Pasay for a press dinner. She addressed the international media present which included former Associated Press bureau chief John Nance; Keyes Beech of the Chicago Daily News; United Press International bureau chief Vic Maliwanag; Mike Marabut and Peter Richards of Reuters; Alice Colet Villadolid of the New York Times; and Pulitzer Prize winner Horst Faas. In the address, she spoke of a “leftist plot to overthrow the government at the expense of the poor Filipino people.” What would shock the media that night was the First Lady’s revelation that her husband would step down from the presidency very soon.

Teddy Benigno, Chief of the Agence France Presse, who was there, recalled that evening:

What suckers we all turned out to be! … the First Lady held court for several hours before announcing the news that was supposed to shock all of us. She said her husband would step down from power very soon… [and] retire into the quiet simplicity of life.

*First Lady Imelda Marcos, with President Ferdinand Marcos. Source: Internet Archive.

Meanwhile, around the same time, Ninoy Aquino and other senators and representatives (Senators Arturo Tolentino, Ambrosio Padilla, Lorenzo G. Teves, and John Osmeña; and House Majority Leader Marcelino Veloso) held a bicameral conference at the suite on the 7th floor of the Manila Hilton at U.N. Avenue, Manila (now the Manila Pavilion). They were working on the Tariff and Customs Code. At 11:00 p.m. the phone rang incessantly in the suite, as warning calls came in.

*Manila Pavilion in the 70′s, formerly Manila Hilton. Source: Carlos Celdran.

At 11:30 p.m. First Lady Imelda Marcos was approached by her personal photographer Marcelino Roxas. President Marcos, she was told, wants her to return to the Palace immediately. She immediately stood up, and apologized for not finishing the program, as she made her way out of the hotel with the Presidential Guard Battalion. According to Marcos’s own account, the First Lady arrived at the Palace at 11:35 p.m. The news of the fake ambush spread around the radio, the last of the radio broadcasts before the shutdown.

*The cover of the unreleased Philippines Free Press, September 23, 1972. Source: Presidential Museum and Library.

At 11:55 p.m. the military arrived at the Philippines Free Press. Editor in chief Teodoro Locsin Sr. tried to make a phone call but the military slapped the phone off his hand, saying that Martial Law has been declared. Immediately the rest of the military contingent swooped in and shut down the press, confiscating all publications and the printer. Some of the staff hid the ready printed Free Press to be released the next day. The unreleased editorial, entitled “Do you want to live under a dictator?” was a self-fulfilling prophecy:

A dictatorship may promise security for its immediate beneficiaries for a certain period of time, but that security cannot last unless the people remain indefinitely submissive and do not rise in rebellion against their condition. The Filipino people did not submit willingly to the dictatorship of the Japanese invaders but fought, as President Marcos himself did, in unflagging resistance to it. He who would ride the tiger of dictatorship, and those who would go along with him, must be prepared to ride the tiger forever. But will the Filipino people allow them to do so till the end of time? The answer to dictatorship is revolution, with all the destruction of life and property that revolutions entail. How many are prepared to pay this price for whatever they may hope to gain from a Marcos dictatorship?

A few minutes before midnight, the Manila Chronicle and the rest of the newspapers were shut down. Chronicle, however, and Taliba, managed to come out with early editions which have already been off the press.

Midnight arrests would follow that would last until morning. As television sets and radio across the nation become static, and without news from Malacañang, panic would ensue.

The Road to Martial Law is a series of blog posts documenting the unprecedented rise of a Filipino dictator and the sudden death of Philippine democracy with the declaration of a nationwide Martial Law via live television on September 23, 1972.

The Road so far:

- It Takes a Village to Raise a Dictator: The Philippines Before Martial Law

- Truth or Dare?: Marcos during WWII

- The Turbulent ‘60s and Marcos’ Ascent to Power

- The Gathering Storm: Beginnings of the Communist insurgency and Moro secessionism in the ‘60s

- The First Quarter Storm of 1970: The Philippines on the Brink

- A Plan for the Endgame: Plots, Protests, Scandals and Assassinations

- Pawns in Cities lobbed with Bombs: Events leading to the Plaza Miranda Bombing

- Hijacking Democracy: The Mood before the Declaration of Martial Law

- September 21, 1972: When Martial Law Had to Wait for One More Day

- Like a Thief in the Night: Martial Law Implemented on September 22, 1972

- The Long Night Begins: Martial Law Announced on Live Television, September 23, 1972

- A Mere Scrap of Paper: The Constitutional Convention Hijacked under Martial Law

- The Final Blow: A compromised Supreme Court legitimized Martial Law

- Road to Martial Law Redux: A Conclusion to a Series

Bibliography

Enrile, Juan Ponce. Juan Ponce Enrile: A Memoir. Quezon City, ABS-CBN Publishing Inc., 2012.

De Quiros, Conrado. Dead Aim: How Marcos Ambushed Philippine Democracy. Pasig City: Foundation for Worldwide People’s Power, Inc., 1997.

Marcos, Ferdinand, “September 22, 1972, Friday, 9:55 pm”, Philippine Diary Project, link.

Mijares, Primitivo. The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. San Francisco: Union Square Publications, 1976.

Rodrigo, Raul. Phoenix: The Saga of the Lopez Family Volume 1: 1800 - 1972. Manila: The Eugenio Lopez Foundation, Inc., 2000.

Salonga, Jovito. A Journey of Struggle and Hope: The Memoir of Jovito R. Salonga. Quezon City: U.P. Center for Leadership, Citizenship and Democracy, 2001.

Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines. Dateline Manila. Pasig: Anvil Publishing, Inc., 2007.

Santos, Vergel O. Chino and His Time. Pasig: Anvil Publishing House, Inc., 2010.

Tolentino, Arturo. Voice of Dissent. Quezon City: Phoenix Press, Inc., 1990.

51 Notes/ Hide

yourstrulyali liked this

yourstrulyali liked this wozziebear reblogged this from indiohistorian

acediscowlng liked this

evilchic reblogged this from introspectivenavelgazer

introspectivenavelgazer reblogged this from hihiyas

introspectivenavelgazer liked this

ccramify liked this

fablenaut liked this

gudetama-tamad reblogged this from the-martial-law-thingy

asteroidflaneur reblogged this from franzwantscoffee

franzwantscoffee reblogged this from the-martial-law-thingy

the-martial-law-thingy reblogged this from indiohistorian

thefictonator-blog liked this

gxldencity reblogged this from the-martial-law-thingy

gxldencity reblogged this from the-martial-law-thingy never-ever-ever-again-stuff-blog liked this

travelingdorks liked this

girl-in-a-well reblogged this from ruscano

earlgreymints liked this

earlgreymints liked this  pitiedparties-blog reblogged this from ruscano

pitiedparties-blog reblogged this from ruscano  ruscano reblogged this from indiohistorian

ruscano reblogged this from indiohistorian  ruscano liked this

ruscano liked this  omamoridayo liked this

omamoridayo liked this yasu-gyaru liked this

jayarea reblogged this from queerhistorymajor

cindywongdelacruz reblogged this from indiohistorian

nofreescotch reblogged this from indiohistorian

queerhistorymajor reblogged this from indiohistorian

morgan-molliniere liked this

morgan-molliniere liked this bunnypop reblogged this from indiohistorian

gudetama-tamad liked this

jehtee liked this

scarfprincess liked this

rakenrollrobin liked this

rakenrollrobin liked this fitzleopoldjames reblogged this from indiohistorian

cecessqt liked this

jeffreybower reblogged this from indiohistorian

onerifle reblogged this from indiohistorian

onerifle liked this

kammartinez reblogged this from indiohistorian

notcakebythemlbs reblogged this from indiohistorian

notcakebythemlbs reblogged this from indiohistorian  notcakebythemlbs liked this

notcakebythemlbs liked this - Show more notes