What was denied to a Catholic priest was granted to a Protestant Pastor. The end became the beginning.

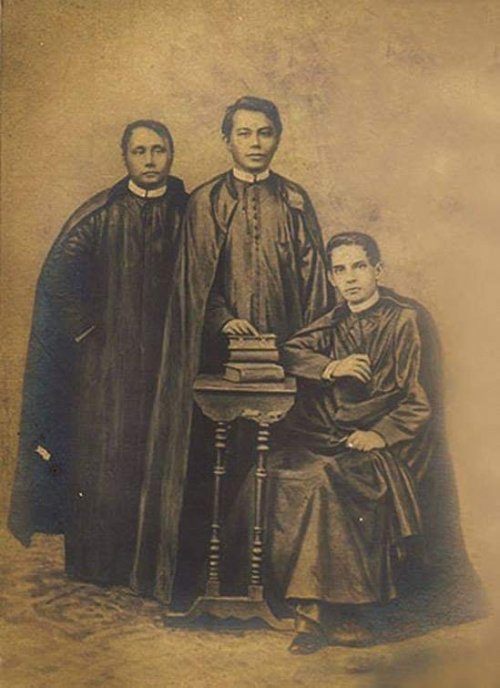

It was on 15 February 1872 when three secular priests—José Apolonio Burgos, Mariano Gómes de los Ángeles, and Jacinto Zamora—were sentenced by the Spanish court-martial to death by strangulation through the garrote. Despite weak evidence, these priests were found guilty of treason as alleged instigators of the Cavite Mutiny in Fort San Felipe, the failed uprising of around 200 Filipinos in the said Spanish arsenal that happened a month before. It must be noted that the three were only among the hundreds who were arrested at the time for the mutiny. But as if singling them out, they were the ones who were to be executed, while others were either exiled or freed.

*Popular engraved depiction of secular priests— Mariano Gómes, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora—known in the portmanteau name in Philippine history as GOMBURZA.

These same priests happened to be some of the active voices that expressed dissent over the redistribution of the parishes, which used to be under the secular priests’ charge, but then were turned over, albeit forcefully, to the Recollects to compensate for the said order’s loss of parishes to the returning Jesuits. These three voices were seen as an affront to the authority of the Spanish friars over Philippine parishes.

A French chronicler, Edmond Plauchut, recorded that in that evening, when the sentence was delivered to the priests, Burgos broke down in tears, as Gomes, having gained maturity brought by age and quiet meditation, only listened. But as for Zamora, the youngest of the three, the injustice perhaps was too much for him to handle, and triggered by intense fear, it made him lose his mind.

That fateful Saturday morning, 17 February 1872, the three priests were executed in Bagumbayan (now Luneta), which as Filipinos would have it, became a rallying cry that would see its fruition in the Philippine Revolution of 1896. That day, the Archbishop of Manila, Meliton Martinez, refused to give in to the Governor-General’s demand of having the priests defrocked. He even had the church bells tolled in their honor, drowning the executioner’s drums.

Zamora, the priest least known of the three, was a Spanish creole and a parish priest of Marikina. Apparently inheriting his advocacy of freedom, a nephew of his, a man named Paulino Zamora, harbored his own resentment of the Spanish friars. Discontented by the rituals of the religion of the friars, Paulino took the dangerous step of having a personal Spanish Bible. It is unclear whether he was able to obtain it via a sea captain through smuggling or through Protestant church leaders in Spain, since sources are conflicted. One thing was clear: Zamora was aware of the danger he was entering into since possessing a personal Bible was forbidden by law. But his curiosity to find out what Scriptures say was a motivation he could no longer put off. He probably got curious of the religion exhibited by the English, that hailed from the Protestant Reformation which sprung up in Europe in 1517. Zamora married Epifania Villagas, and she bore him their son, Nicolás Zamora, on 10 September 1875.

Paulino Zamora’s family moved to Bulacan, away from the watchful eye of religious authorities, so they could freely read the Scriptures together. Nicolás, roughly at 12 years old, listened intently. The Bible group slowly began to attract neighbors by word-of-mouth, who were also curious of what the Scriptures really say of God, heaven, and salvation, and why such a book was prohibited to be read privately by individuals in the colony. Meanwhile, Paulino had his son taken care of by his brother, Fr. Pablo Zamora, who was a curate at the Manila Cathedral. The priest, in wanting Nicolas to pursue law or the priesthood, led him to enroll in the Ateneo de Municipal, obtaining a Bachelor of Arts degree. Eventually shifting his track into law, upon graduation in Ateneo, Nicolas enrolled at the Universidad de Santo Tomas.

The outbreak of the Philippine Revolution in 1896 changed everything. The Spanish authorities heard of Nicolás’ father, Paulino Zamora’s, religious activities. Paulino was immediately arrested without trial and exiled halfway across the world to Chafarinas Islands, a penal settlement in the Mediterranean, off the northern coast of Morocco. Meanwhile, Nicolás, aggrieved, left his studies to join the revolution, eventually being drafted into General Gregorio del Pilar’s army. As the revolution raged, Nicolas made time to study the Scriptures for himself in the frontlines. Eventually he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.

*Photo of Methodist Bishop James M. Thoburn who paved the way for the establishment of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the Philippines. Courtesy of the Filipino Methodist History Facebook Page.

With the Treaty of Paris signed in 1898, Paulino Zamora was granted amnesty and was allowed to go back to the Philippines. Paulino made sure he attended his first Protestant worship service in Spain and purchased evangelical readings from Spanish Protestants before he went back. Overjoyed upon hearing from his son the new religious freedom in the country under the Americans, the father and son were avid supporters of the first Protestant missionary activities in the country under Methodist Bishop James Thoburn and Arthur Prautch, that began in March 1899. By June, Protestant services that catered specifically to Filipinos, with an interpreter, was held in Teatro Filipino in Quiapo, Manila (where SM Quiapo stands today). On the fourth Sunday, Prautch’s Spanish translator did not make it to the service. Prautch asked Paulino to speak instead. The father, however, knowing the oratorical skills of his son, recommended Nicolás to face the thirty people gathered there. It was here when Nicolás shined, as he told his story, of his late great uncle, Jacinto Zamora, of their travails in wanting to read the Bible in the language they understand, and his own personal journey to faith. The people present were deeply moved by his testimony that Nicolás was asked to speak again the following Sunday. That Sunday, promoted in broadsheets across the country, was attended by a large crowd and Nicolás’ message was received with great impact.

Eventually Paulino Zamora, upon the proddings of James Rodgers, a Presbyterian missionary, became affiliated with the Presbyterians. Nicolás preferred to stay in Methodism, and he eventually became an active member of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Nicolás’ ascent from a mere deacon holding itinerant preachings in several locations to an ordained pastor was breathtakingly fast, if it is to be compared to the slow struggle of the secular priests against the Spanish friars from before. Recognizing Nicolás’ zeal and passion for the Gospel, it was Bishop Thoburn himself, and Bishop Frank Wayne, another Methodist leader impressed by Nicolás, who went out of their way for Nicolás’ ordination as deacon to happen. Commenting on his preachings, Wayne wrote, “He was a good man, educated, married, converted, eloquent, knew his Bible and abundantly qualified to preach.” Not long after, he became a fully ordained Protestant minister, the first in the country.

Gaining a following, with his powerful preaching in Plaza Goiti in Manila, Nicolás Zamora’s pulpit became known in downtown Manila and beyond. He would hold debates with priests which would draw large crowds. By 1902, Nicolás was ordained as elder, and by 1903, he was assigned as the first Filipino pastor of the Methodist church at Avenida Rizal (now known as Knox United Methodist Church). Under his leadership, the church grew exponentially in membership.

*The Knox Memorial Methodist Episcopal Church (now the Knox United Methodist Church) in 1907, courtesy of the Filipino Methodist History Facebook Page.

Dr. Dionisio Deista Alejandro, the first elected Filipino bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, recounted, upon being interviewed by Richard Deats:

“It was my happy privilege to have listened several times to Pastor Zamora’s preaching way back in 1906 and 1907 at the Teatro Rizal on old Ilaya Street, corner Azcarraga. The theater, with a seating capacity of over a thousand, was always full on every Sunday I worshiped there. He was a great speaker, oratorical, somewhat bombastic in style, but mighty and sincere in expression. He had a terrible booming voice that could easily be heard all over the place and outside where a throng of late comers always could be found. He used good, very good Tagalog, embellished with Latin quotations from the Bible and interspersed with Spanish phrases.”

While all was well in his ministry, Nicolás Zamora encountered condescending and racist comments even from among his American colleagues. One time, he overheard someone in a seminary say that Filipinos would never be good pastors. Another time, one wrote that “For all their veneer [they are still] primitive and childlike.” Zamora never left his nationalist ideas. In fact, it was his Protestant faith, with emphasis on the Christian’s individual conscience, direct access to God through Christ, personal reading of the Scriptures in the vernacular language (not from Latin, but from the original languages of Hebrew and Koine Greek), and the free gift of salvation by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone, that intensified it all the more. Perhaps alluding to the Protestant movements that encouraged people to read the Bible in their own ethnic language/dialect, Zamora’s wish for the Filipino church to be free of foreign control intensified.

*Portrait of Nicolas Zamora, courtesy of the Filipino Methodist History Facebook Page.

Finally on 28 February 1909, at St. Paul’s Methodist Church in Tondo, Manila, Zamora told the congregation that he will be leaving the American-controlled Methodist church to form the La Iglesia Evangelica Metodista en las Islas Filipinas (IEMELIF). Twenty five out of the 121 local preachers joined Zamora. Upon closer analysis, those who joined Zamora in this new independent church belonged to the generation of Tagalogs who were animated by the Philippine Revolution and have never given up on insisting on a uniquely Filipino way of Christian worship, despite the overwhelming American influence in the country.

As if echoing the late great Protestant missionary to China, J. Hudson Taylor, who advocated for the indigeneity of the Christian message, Zamora uttered these words in one of his sermons:

“It is the will of God for the Filipino nation that the Evangelical Church in the Philippines be established which will proclaim the Holy Scriptures through the leadership of our countrymen.”

Zamora, unexpectedly, died of Cholera in 1914, at the age of 39, two years longer than that of his great uncle, Jacinto Zamora. But his legacy lives on in the Protestant expression of Filipino spirituality today.

–

In commemoration of the Protestant Reformation that began in Wittenberg, Germany in 1517 and ignited the Evangelical faith and the Modern World.

It’s also Pastor’s Appreciation Month this October among mainline Protestant and Evangelical churches.

–

*ABOVE: Portrait of Nicolás Zamora from the Filipino Methodist History Facebook Page.

*Special thanks to my fellow colleague researcher in NHCP, Eufemio Agbayani III, Vice President of the Historical Society of the United Methodist Church-QC PACE, who helped me supplement this blog post with vital facts on Philippine Methodism. :)

33 Notes/ Hide

bumalikwas liked this

mariaclarareincarnate reblogged this from indiohistorian

queerhistorymajor liked this

scurvyoaks liked this

xinlingmei liked this

goldpeninsula reblogged this from indiohistorian

feels-before-wheels liked this

painsmemory liked this

madewithonerib said: Thus sin for which many are represented as being punished, [Revelation 9:20] is said to be their worshipping, τα δαιμονια, demons, that is, angels & saints; not devils, as our translators have rendered the word. tmblr.co/ZK2KqV2…

officialhit0mi liked this

abagat liked this

yasu-gyaru liked this

yasu-gyaru reblogged this from indiohistorian

srfudanshi reblogged this from indiohistorian

srfudanshi liked this

nablah liked this

nablah liked this theheadsup liked this

infinitewordss reblogged this from indiohistorian

infinitewordss reblogged this from indiohistorian  lazyass-aiden reblogged this from indiohistorian

lazyass-aiden reblogged this from indiohistorian primejeuz liked this

masokistangadventurer liked this

brenli liked this

xscizors reblogged this from indiohistorian

xscizors liked this