Subscribe to the Grand Strategy Newsletter for regular updates on work in progress.

Discord Invitation

Post with 6 notes

Counterfactuals about Mayan Civilization

In The Dissolution Threshold I made some remarks about the long, slow decline of Mayan civilization. The decline of Mayan civilization did not occur in a vacuum. I take Mayan civilization to be one among the civilizations that constitute what I call the Mesoamerican cluster. Mesoamerica and what is today Mexico were highly productive of civilizations. There were the Olmecs, the

Teotihuacan, Zapotec, Mixtec, Huastec, Purepecha, the

Toltecs, the Maya, and the Aztecs. Possibly there were others as well.

The Maya were among the largest and the longest lasting of these Mesoamerican civilizations of the Mesoamerican cluster, and the only pre-Columbian civilization in the Americas to develop a written language (Quipu was a record keeping device, but not a written language – an interesting counterfactual would be a civilization that developed elaborate record keeping systems like the Quipu, but to a higher degree of sophistication, without developing a written language; this might have happened in South America if the Europeans had not come). The Olmecs may have had a written script, but the evidence at present is ambiguous; interestingly,

Nahuatl

became a written language after the Spanish conquest, using Roman characters.

Suppose that the Maya were more isolated, and that they did not appear among a cluster of civilizations, except perhaps for predecessor civilizations. Suppose that the Mayan civilization followed its known trajectory of development and dissolution, but no Aztec civilization arose to the north (or, if it did, it was much further away, so that it was not an immediate influence). Suppose further that Europeans did not arrive when they did, so that the development of civilization in the Americas continued uninterrupted in its indigenous development, at least for another several hundred years, if not for another thousand years.

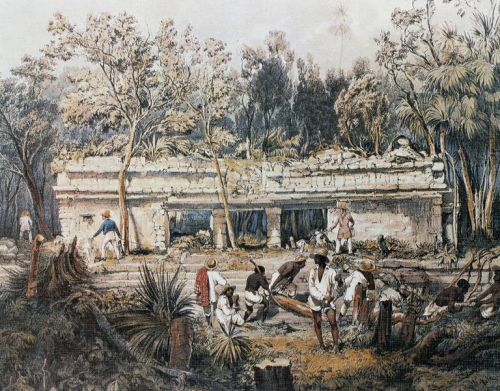

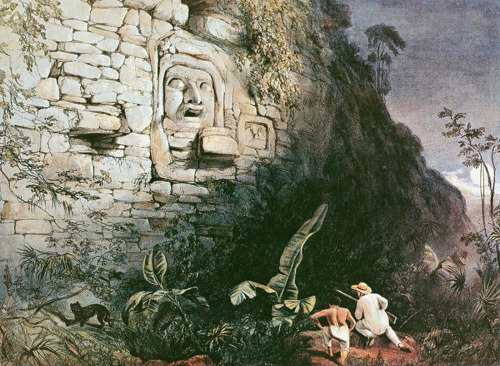

The Mayan people would have been surrounded by the monumental ruins of their previous civilization – much as the people of medieval Europe were surrounded by the monumental architecture of the Roman Empire – though these ruins would have been rapidly overtaken by the tropical rainforest, as in fact they were. Mayan life would have continued on a scale of much lower population density and much less social and technological sophistication.

Suppose, however, that not all of the Mayan civilization were lost. Suppose that the daykeepers continued to keep the Mayan calendar (as in fact they did), and, since no Spanish language would have displaced the native language in this counterfactual scenario, further suppose that the daykeepers continued to keep their record of the Mayan calendar in the Mayan language (as in fact they did not).

Certainly over time the Mayan language would have changed, just as Latin changed from the Latin spoken by the Romans into the Latin spoken by the Catholic church and monks who studied ancient Latin manuscripts, but there would be enough of a continuity that later ages, looking back, would be able to rediscover their link with the past.

If civilization were, under these counter-factual circumstances, to emerge once again in the region, or in a nearby region, also a civilization of the Mayan people (like the earlier Mayan civilization), we would in retrospect be likely to term the period between the end of the first Mayan civilization and the beginnings of the second Mayan civilization a “Dark Age” for Mayan civilization, whereas today we do not identify a Mayan Dark Age because Mayan civilization and the Mayan people have become submerged under a transplanted European civilization.

Moreover, we would recognize a tradition of Mayan civilization that was constituted by more than one Mayan civilization – distinct civilizations in time, but part of the same tradition, with the later being the inheritor and descendant of the former.

Both the rise of the Aztecs to the north – which, as part of the Mesoamerican cluster, borrowed from the common cultural stock of the region – and the arrival of the Europeans in the Americas, served as preemption events that, by their presence and their influence, displaced any long-term development of the Maya civilization. This also had the result of “eliminating” a Mayan Dark Age, though whether this elimination is a matter of historiographical interpretation, or has some ontological relevance for Mayan civilization, is another question.

I mentioned in my previous post that most historians today don’t use the term “dark ages” and indeed sedulously avoid it, and that it has, after being abandoned by academics, become a term of “folk historiography.” Yet my previous couple of posts, along with this one, make me realize how useful the concept of dark ages can be. There is a lot of interest today in the topic of civilization collapse, partly made respectable by the study of global catastrophic risk and existential risk, which now has the Oxbridge stamp of approval and no longer need be consigned to Chicken Little Status.

A dark age is what happens after the collapse of a civilization, unless some

preemption event

occurs to change the course of history. In the event that a global catastrophic risk or an existential risk is realized – whether in the past, now, or in the future – the result would be either the extinction of civilization or a dark age for civilization. This is a difference that matters, and it would help if we could talk about dark ages without embarrassment in order to make this crucial distinction.

skeletontemple liked this

chats-discutent liked this

zerofarad reblogged this from bloodandhedonism

zerofarad liked this

bloodandhedonism liked this

bloodandhedonism reblogged this from geopolicraticus and added:

@tomasnau

geopolicraticus posted this