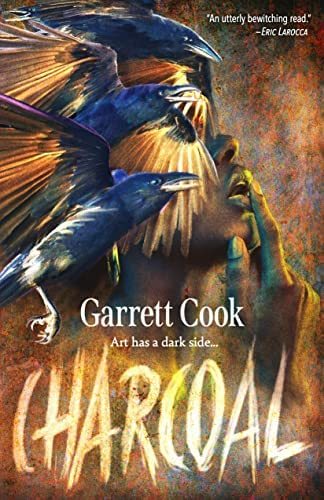

Garret Cook’s Art-School Gothic Charcoal Is in a Class All Its Own

Garrett Cook’s Charcoal is in a class of its own. While the story, with its tales of mad artists, haunted paintings, otherworldly patrons, and grand guignol kill scenes might proudly hearken back to more traditional gothic tales, Cook firmly roots this in a grittier, more unnerving present, bringing those traditional gothic ideas into modern focus: The poetic and the profane sit side-by-side in his prose, often in the same sentence, adding a certain grit to the lurid nastiness. The “mad artist's” mental illness and trauma is explored in depth, with an utterly wrenching degree of focus and empathy. The otherworldly retribution is set in a modern context of toxic power fantasies, allowing vindication, but also showing the consequences and mental toll of revenge. But perhaps its most crowning achievement is that rather than revel in its bleakness, it explores the toxicity of “tortured artist” tropes from every angle and shows that there’s more to art than pain, rage, and hunger. It’s a twisted exploration of the modern hurdles of an artist and someone forced into dealing daily with toxic people in a toxic environment, one that shows both highs and lows with rage and passion in equal amount. All of it, like the best art, both genius and depraved.

At an unnamed art school in New England, Shannon Hernandez finds herself overwhelmed. Jameson, her art professor, is a creep. Her classmates are the kind of jerks who take most of their personality from toxic subreddits, or simply unable to stand up to the professors’ bullying. And her own art lacks…something, according to friends and jerk classmates alike. During a classroom argument between Shannon and Professor Jameson, Shannon uses a set of charcoals supposedly made from the bones of Thomas Kemp, a horrifying deviant known as “The Libertine” and rumored to have kidnapped and tortured women in exchange for (dubious) artistic talent. In a mad frenzy, Shannon paints something new, something dangerous, something that will drag her down a disturbing path where hallucination and reality blurs, a path beset by a cabal of mutilated artist-monsters and their demonic patron, and a whirling crowd of crows who seem to act on her every move. It will bring her dark gifts, and terrible hunger. Revenge, and power beyond imagining. And all she has to do is create.

Charcoal’s depiction of obsession and mental illness is terrifying in its authenticity. Shannon’s descent into madness is agonizing to watch. Her world shrinks, to the point that outside of her apartment, the studio, and the twisted dreamscapes she visits nightly, there aren’t many places she goes. Outside of a few named characters, people seem to know Shannon more than she knows them, with her wondering when they met and why, since she doesn’t remember much about them, they seem to remember her. One particularly horrifying moment when Shannon is at her lowest describes the claustrophobia of her world shrinking to a single dot, a box within a box within a box in her apartment. It also ties into the more supernatural elements, as the more Shannon uses Kemp’s charcoal and the more freely she allows Kemp and her flood of black crows to operate, the more Kemp acts as a kind of intrusive voice challenging her every thought and action and the more the crows eat away at her memories, the way intrusive thoughts can frequently turn contradictory and accusatory, or the way various mental illnesses “eat” memories both harmful and happier in an attempt to warp one’s mental state. It’s a twisted but refreshingly honest look at disassociating, distancing oneself from harm, and the way trauma responses can ultimately cast toxic influence over every aspect of a person’s life.

Cook also tears the ideas of “sacrifice for art” and “salvation from pain” to shreds. While the Cenobite-esque trio of monstrous artists that follow Shannon around as her power grows are in some way pained, that doesn’t excuse the horrifying deeds and literal human sacrifice they engaged in when they put their depraved gifts to use. Art doesn’t save Shannon, either, as much as it leads her spiraling away from salvation, with Shannon putting her toxic feelings on the canvas, but creating more and more toxic emotions and situations to feed into art until the point that she starts committing murder to feed the hunger inside her, literally sacrificing other people and even her own memories to her artwork. There are even parallels between her own crimes and the power dynamics in her life, as she brutally sodomizes her victims and then feeds their remains to her charcoal crows and ghostly companion to make new portraits. Similarly, Shannon spends an early part of the book obsessing over her dorm-mate Rem, even striking up a relationship with them, but eventually ghosts Rem and instead pursues the far more toxic and networking-driven art world because Rem feels too good (and Shannon believes she doesn’t deserve something like that), and because she needs to make sacrifices and make more deals with the literal and figurative devils in her life for the good of her artwork. She even turns the moments where she felt powerful with Rem into moments of violence she visits upon the “deserving,” trying to recapture that feeling of power without understanding it. It’s not until she finds power in herself, the self existing in her more beautiful memories and healthier emotions that her art starts to get better.

And that power, that interplay, that emphasis on the negative side of trauma and oppression and power dynamics, is what drives Charcoal. A lot of Shannon’s internal monologue is focused on what’s missing, what she needs to take from others, what others take from her, and what she needs to “get back” or “take back” in the process. And indeed, a lot has been taken from her. She’s a Black queer latine who lost her father at a horrifyingly early age and who is viewed by the men around her as simply someone they can push the right conversational buttons with or exert the right amount of power with to use her for sex, or to piggyback on her talent, or any number of other things. Even the inciting incident that puts her in contact with the charcoals is a classroom showdown over the idea of “separating art from artist,” forcing her into becoming a spectacle just for speaking up, pushing her into a choice between public humiliation and a loss of autonomy. But there’s no catharsis in the vengeance she wreaks, nor a sense of justice. Shannon even wonders herself at a certain point if her victims– monsters though they are– deserve her acts of violent sodomy, getting torn apart by crow spirits, and then turned into artwork at her hands.

But it isn’t all about darkness and toxicity. There are moments where the idea of holding on to beauty and joy even when all around is dark shine through. It’s even the thing that finally does give Shannon the fulfillment she desires– not in “taking back,” not in revenge or death by crows or her final gory tableau– but in the beauty she tries to capture in simple forms, the things she makes for herself, and the art that is ultimately all hers, not the charcoal’s, not the crows’, not Kemp’s, but in the power of creation used to make something that affirms her life and reflects what she wants to build. It’s in that moment that the demons finally release their hold, that Shannon finally finds the catharsis she’s looking for through her art. Which, when depicted in Cook’s gorgeous, poetic, and somewhat overwhelming voice, makes it all the more beautiful.

It’s what makes Cook’s Charcoal the most refreshing variation of the “mad artist” story to date. Its authentic depiction of mental illness, discusses the effects of trauma and oppressive power dynamics on mental health, and brutally shreds the idea of a “revenge” narrative by showing the dire and upsetting effects of wielding power for toxic ends. But while it’s an easy task to knock something down, it’s in those moments of beauty and fulfillment and the idea that there’s a road away from the all-consuming swirling nihilism of the dark that Charcoal finds its heart. It’s a brilliant enough story without that– one part Hellraiser, one part American Psycho, and one part Koja’s Skin– but as we all know, the best art has emotion, ideas, and focus behind it. And Charcoal can and should easily count itself among that exclusive class.